Irascible and indomitable, the British Seagull was not for the faint of heart.

Issue 134: Sept/Oct 2020

Long before the Energizer Bunny, there was the British Seagull outboard motor. Conceived in the 1930s, it was ugly, dirty, loud, and smelly, but like the bunny, it kept going. And going. It kept going so long that it became a collector’s piece, a cult engine. Many are still in use today, more than 60 years after manufacture, often clamped to the transoms of vintage wooden yachts.

The passing years have endowed the British Seagull with its own folklore. The yachting scene is awash with stories about Seagulls, mostly apocryphal, but plenty of them true enough. For example, there’s the one about the Seagull that was used as an emergency overnight anchor. It was recovered the next morning, attached to the transom, and started at the third pull.

And there’s the Seagull story to cap all others, the one about the motor that was recovered by divers after 10 years under water. It, too, started at the third pull. (As far as storytelling goes, the third pull is a nice touch. Nobody would believe you if you said it started at the first pull. But the third pull adds a touch of verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative, which ensures that the story, like the engine, will keep going and going.)

Some stories are based on facts that just might be true, but probably aren’t, such as those insisting that a Seagull will run on kerosene—or even sunflower oil—in a pinch. Others bear the ring of truth, like this one from a sailor in New Zealand who wrote on a sailing bulletin board: “Had a Seagull backfire and start running backwards. Starter cord was still hooked in the slot. Starter cord gave me a good whipping, about 15 good welts down the back of my arm before I could rip the plug wire off. I found the base plate loose and the timing was out.”

To anyone stumbling across a Seagull for the first time, it must be an odd-looking beast. It could have come straight off Rube Goldberg’s drawing board. At first sight, you’d be forgiven for thinking that someone had at last discovered the missing link between oars and Evinrudes. Someone might even have dug the original Seagull out of the fossil beds of the white cliffs of Dover.

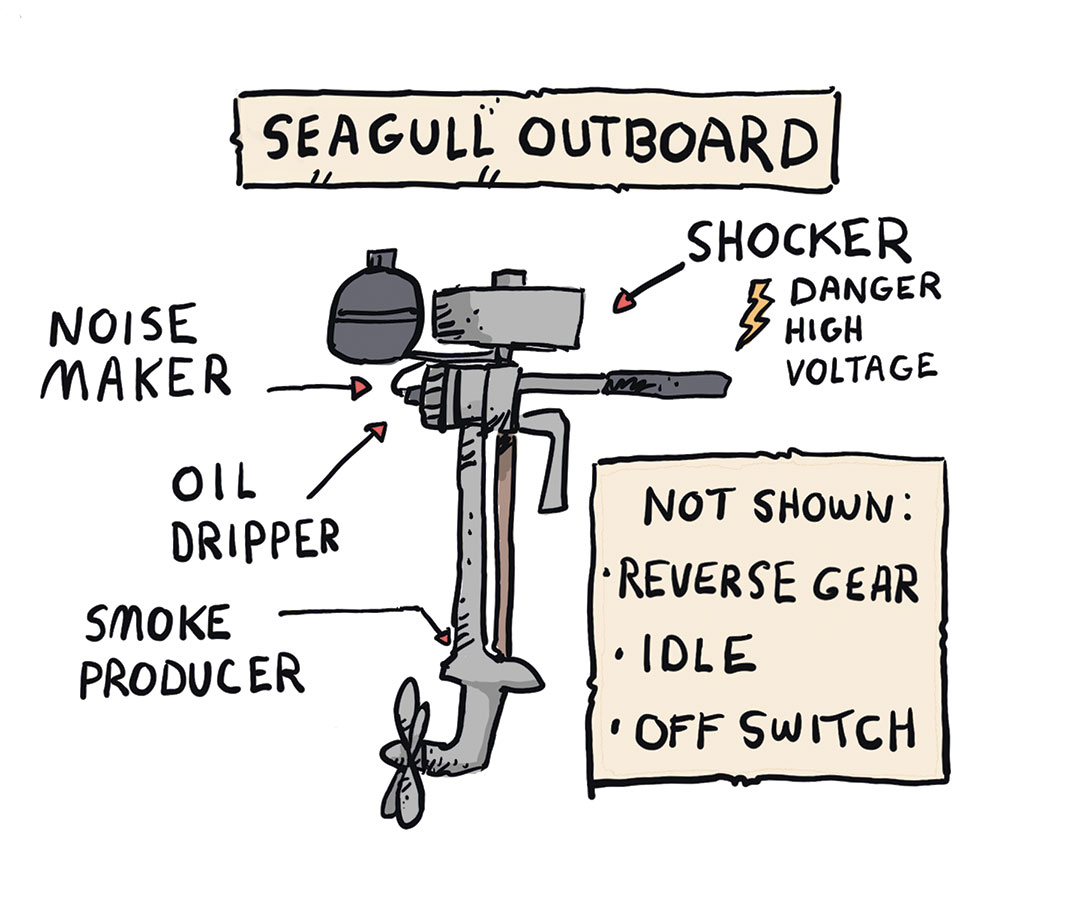

As a piece of engineering, it is primitive in the extreme. It could have been designed by an 11-year-old with an Erector set—a couple of long pipes with a disc on top and a large propeller at the bottom. There was a metal gas tank perched up high and a rudimentary carburetor on one side. At a guess, it might have been an overgrown kitchen blender, or a hedge cutter, or a portable fan.

Could this strange machine possibly have come from the same country that made those superb Sunbeam motorcycles? The same country that invented Rolls-Royces and Spitfires? Well, yes, actually.

Two engineers share the credit (or blame) for inventing the Seagull, a machine that was one small step for man and one large step backward for mankind, environmentally speaking. They are John Way-Hope and Bill Pinniger. Both men worked for the marine division of the Sunbeam Motor Company.

They produced the first Seagulls in the 1930s, and the design remained essentially unchanged for the next 60 years until production ceased in 1996. Their idea was to build an engine that was simple to operate and maintain, a lightweight, portable outboard designed to drive a small, slow-moving boat at hull speed under all conditions of wind and sea. To this end, it was given a large multi-bladed propeller with a fine pitch.

As far as maintenance went, it was said that all you needed in the way of tools was a pair of pliers, a screwdriver, and an adjustable wrench.

There were two engine blocks, each supporting a single cylinder. The first, displacing 64 cubic centimeters and known as the model Forty, produced between 11/2 and 3 horsepower. The second engine, displacing 102 cubic centimeters and known as the Century model, developed anything from 4 to 6 horsepower. The differences in power came about because over the years there were some 90 variations of the two basic designs in the form of different carburetors, gear ratios, propellers, and shaft lengths.

During the Seagull’s heyday in the 1970s, the factory was producing about 80,000 engines a year. Some—just a few—featured a dog clutch and neutral gears, but on the majority of Seagulls, the propeller kept spinning as long as the engine was running. That, combined with the fact that there was no way of stopping the engine quickly (unless you were lucky enough to have an extra-long throttle cable that would push past the idle position) made coming alongside a boat, a pier, or a mooring buoy fraught with excitement.

Now, more than 60 years later and more than 20 years after they were last manufactured, there are still hundreds of used models for sale in various parts of the world. And plenty of spare parts, too. You’ll find lots on eBay and on several specialized British Seagull websites.

Admittedly, this homely little engine exudes a certain air of je ne sais quoi, but that doesn’t explain why it is so sought after, although part of its popularity may be due to the endearing eccentricity that surrounds the Seagull. The people who built it and sold it were undoubtedly eccentric, so it’s no wonder they produced an outboard reminiscent of a smelly old uncle set aside at a family reunion—disreputable, but still loved.

Who else would build a motor that had no clutch, or reverse gear? Who else would build an engine without a cover, with an exposed magneto flywheel? A motor you had to start by twisting a bit of rope around the flywheel and pulling like crazy until whiplash made you (and anyone else within range) give up.

In the eyes of the Seagull’s builders, to provide a clutch on an outboard motor was to pander to weak-minded sissies. The same applied to a recoil starter. Real sailors used a real starter cord. And only wimps complained when the sleeves of their sweaters were ripped off by an exposed, whirring magneto flywheel. Buyers of Seagulls were expected to display a stiff British upper lip, dammit.

I first became aware of the manufacturers’ eccentricities when my friend, Bernie Borland, wanted to buy a 51/2-horsepower Seagull for a small sailboat he owned. While he was in England on business, he went to Seagull headquarters in Poole, Dorset. There he met a woman he understood to be the owner of the British Seagull factory.

“I’d like to buy a 5 1/2-horsepower Seagull, please.”

“What for?”

“How do you mean?” Bernie asked. “It’s for a boat.”

The woman stared right back. “What boat?”

“An 11-foot boat. An International Mirror.”

“You can’t have it,” she said. “I won’t sell that motor for a Mirror, it’s too big. Seagulls like to run hot, under load, otherwise they oil up. I’ll sell you a 2½-horsepower model, the Forty. Nothing more. It’s plenty.”

And so Bernie, despite feeling somewhat browbeaten by Ms. Seagull but strangely privileged at having been allowed to buy one of her engines, came flying home with a small Seagull in his excess baggage. It was, as the woman said, plenty.

The Seagull Owner’s Handbook was another example of corporate eccentricity. “The world of engine owners is divided into two classes…the vast majority are those who never get into any trouble and get heaps of pleasure, whilst the second class is a very small minority, which is always in trouble, causing misery to itself and constantly drawing on the kindness and good fellowship of other people for aid and assistance.”

This mournful document was not a great deal of help when it came to advice about what to do if your engine wouldn’t run. There was little information in the way of a troubleshooting guide to turn to. The Seagull experts had boiled it down to only one suggestion: “Check the spark plug.”

And in case owners didn’t quite understand this simple advice, the handbook continued: “But will people do this? No, they won’t . . . instead, they go on pulling the starting cord for twenty minutes or so, pumping more and more petrol into the engine, filling the plug with oil, and then have to row home, and sometimes (if they’ve got the strength) write a furious letter to the manufacturers. We have no sympathy with these people at all . . .”

One has to wonder how many furious letters provoked them to include this addition.

In my youth, I motored hundreds of miles on European waterways. The boat was a 17-foot daysailer. The motor was a Seagull. Its single cylinder housed a very sloppy piston, topped by a spinning, exposed flywheel that allegedly made electricity for the spark plug. Tacked on to one side was the simple carburetor. The float bowl had a small button sticking out of the top that I knew to press down with a finger until the whole thing flooded and overflowed with gasoline. This was known in Seagull circles as “tickling the carb.” A spreading rainbow sheen on the water around me was my signal to wind the starter cord around the disc on top, flick closed the crude metal slide that served as a choke, and pull like mad.

After I was hit on the back of my neck by the starter cord as it came off the flywheel, there were two ways I had to tell whether the motor had started or not.

The first was to listen for a great echoing, gurgling roar, a noise fit to wake the dead. Anyone could hear a Seagull coming from miles away. The second was to observe a great cloud of blue-white smoke rising from the water astern. That was the exhaust, which consisted of 50 percent burned gasoline and 50 percent lubricating oil, just slightly singed by the Bronze Age combustion process.

The exhaust added its own smear of oil to the water around the stern, of course—though smear might be too wispy a word to describe the fearful results of a Seagull’s passage through the water. It was often said that you couldn’t get lost if you had a Seagull; you just followed the smoking oil streaks back home.

One afternoon, while I motored along an otherwise quiet canal in Belgium, the gas tank fell off and nearly went overboard. I screwed it down to the afterdeck and fed gas to the carburetor via a plastic tube. It worked just fine that way.

As forecast in the owner’s manual, the spark plug frequently oiled up and stopped the engine, usually in moments of crisis, often when a huge barge was approaching head-on and seeming to fill a narrow canal. At times like that I needed asbestos fingers to remove the old plug and screw in a clean one with lightning speed.

My Seagull was a two-stroke, of course, so I had to mix thick, gooey engine oil in with the gasoline so that the clunky bits inside the engine received adequate lubrication. Built before 1979, mine ran on a gas-to-oil mixture of 10:1. Later models ran on a ratio of 1:25 (even this was about four times as much as modern two-strokes used before they were deemed unacceptably polluting at 100:1). The Seagull was (and still is) the ultimate global-warming machine.

As I suspect is the case with all Seagulls, mine had its unique set of eccentricities. It wouldn’t start if the exhaust pipe was too far under water (the back pressure was too much). It overheated if I left it to idle (the water pump couldn’t lift water to the power head at low revs). There was a strange seal at the prop shaft that seemed to have been deliberately designed to leak. The seal allowed oil to escape. Water replaced it, and the gearbox was filled with a gray-brown slurry. I learned later that Seagulls were designed from the beginning without a proper oil seal, the gears were expected to run on an emulsion of oil and water. It seemed to work just fine.

To be fair, there were some advantages to the Seagull. For a start, it made people laugh. The noise and the smoke attracted attention to itself and its owner. It would run while tilted over to an angle of 45 degrees when we were under sail. And, finally, a Seagull owner could throw it away in a fit of rage without feeling any remorse.

I’ll leave you with some Seagull thoughts from the well-known boating writer, editor, and Seagull owner, Chris Caswell, the winner of more than 50 awards for writing and yachting journalism. Chris has been the editor of Sea magazine and a longtime senior editor of Yachting magazine, so he knows what he is talking about:

“So how do you stop a Seagull? In theory, you could just shut off the fuel, which would kill it in an hour or two. But, since the sturdy four-bladed prop was still spinning, that wasn’t realistic in most situations. One way was to put your hand over the carb air intake but, if it happened to backfire before stopping, it would install a perfectly round (and quite painful) blister on your palm. Another way was to pull the plug wire, but if it wasn’t absolutely insulated (and it rarely was), this would provide great amusement to anyone watching as you did a St. Vitus dance from a blast of electricity. I knew one Seagull owner who kept a short length of lumber that he would shove carefully into the prop to stall the engine…

“Thinking back on the Seagulls I’ve owned, I wish I had one now. Smelly, noisy, and oily, Seagulls were like an aging favorite dog with fleas and mange, you loved it anyway. I’d hang the Seagull on my wall like a museum piece, just so I could look at it and I’d laugh and relive my childhood memories. The Seagull taught a generation of sailors about boat handling, and even today I never get in a dinghy that doesn’t have oars.”

John Vigor is a retired journalist and the author of 12 books about small boats, among them Things I Wish I’d Known Before I Started Sailing, which won the prestigious John Southam Award, and Small Boat to Freedom. A former editorial writer for the San Diego Union-Tribune, he’s also the former editor of Sea magazine and a former copy editor of Good Old Boat. A national sailing dinghy champion in South Africa’s International Mirror Class, he now lives in Bellingham, Washington. Find him at johnvigor.com.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com