…and a couple North American racer/cruisers

Issue 128: Sept/Oct 2019

The 1980s were a transformative period in the sailboat industry in North America. After years of incredible expansion in the 1970s, the International Offshore Rule (IOR) was falling out of favor, and a suitable replacement had not yet been found. (Some would argue that a suitable replacement has yet to be found!) Builders of dual-purpose sailboats were taking a beating because they were often competing against their own boats on the used market, as well as fighting the emergence of one-design “around the buoys” keel-boat racing and “sport” boats. At the same time, shoal-draft cruising boats, a maturing trawler market for aging sailboaters, and the emerging popularity of multi- hulls all contributed to fragmenting the market. When you add in the additional challenge of competition from both Taiwan and France, things really started to get tough!

A number of North American builders did not survive the 1980s. Those that did were then hit with the 10% luxury tax in 1991, a tax that turned out to be the final straw for many more. However, the boats built in the 1980s are still some of the finest good old boats out there today.

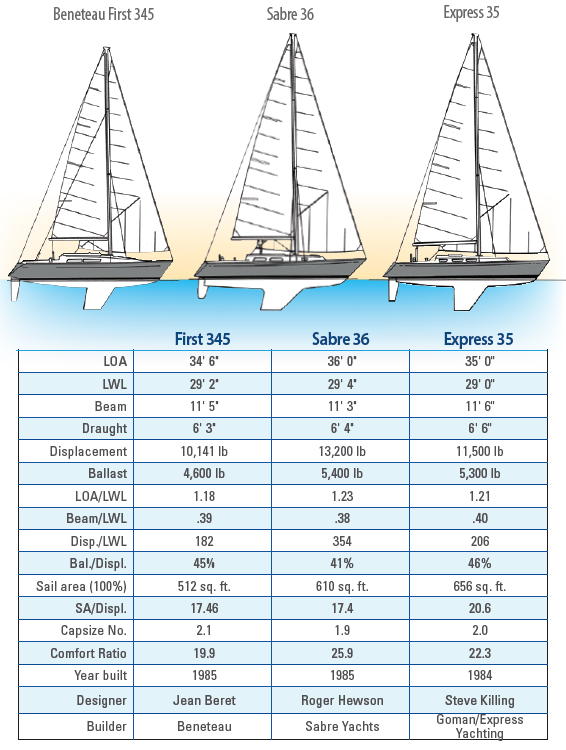

The Beneteau First 345 is a classic example of the 1980s competition from France (the “French Invasion”). As a comparison to the French Beneteau First 345, let’s take a look at two North American boats designed and built in this same period that target the same shrinking dual-purpose racer/cruiser market: the Roger Hewson-designed Sabre 36 and the Steve Killing-designed Express 35. (The latter was built by another C&C alumnus, Bill Goman of Goman/Express Yachting.) All three boats are surprisingly similar in their dimensions and design philosophy, reflecting the established influence of the IOR, this time in a positive way, because they are all good wholesome boats. But the emergence of the IOR “type” is obvious and well illustrated in all three.

Each has the now-standard split keel and rudder, with low wetted surface, and a tall sail plan incorporating a mast head rig with double spreaders and a large fore triangle. Each bears the IOR hallmarks of a straight stem, and a small skeg above the rudder to “tweek” the after girth stations, as well as, I suspect, but cannot confirm, possibly U-shaped forward sections and flatter midship sections. Of the three, the Sabre looks to be the more conservative design with the larger and elongated rudder skeg extending forward to the keel. This certainly increases wetted surface and impedes maneuverability, but does improve directional stability. The waterline lengths, max beams, and draft are all within inches of each other. There is about a 3,000-pound variation in displacement, but how much of that is actual, and how much is marketing is always an open question. As we have discussed in the past, sometimes “designed” displacement is not always realized in a production environment. The lighter 10,141-pound displacement of the First 345 on essentially the same waterline length as the other two boats yields the lowest displacement/length (D/LWL) ratio of the three at a very competitive 182, followed by the Express at 211, and a still-competitive 234 for the 13,200- pound Sabre. The lighter First 345 has the smallest sail area at 512 square feet, but still produces a high sail area/ displacement (SA/D) ratio of 17.46, essentially equal to the heavier Sabre, which carries almost 100 square feet more sail! However, the 11,500-pound Express carries the most sail area on the tallest rig of the three, for a very impressive SA/D ratio of 20.6. That would make the Express a hard boat to beat in light air on any point of sail. As the breeze builds, though, the heavier displacement and greater ballast weight of the Sabre would give her a distinct advantage upwind, but off the wind in those conditions, the First would certainly have the edge.

A lighter displacement combined with a relatively wide beam pushes the capsize number of the First 345 slightly above the 2.0 threshold, while the heavier Saber is slightly under, and the Express right on 2.0. The heavier displacement of the Sabre, along with the narrower beam, results in the best comfort ratio of 25.9, with the other two falling in line in direct relation to their lighter displacements.

I look upon the boats from this era as the finest product of the late IOR. Most of the more egregious exploitation of the rule prior to the 1979 Fastnet Race had been eliminated, and the boats produced by almost all builders were becoming more sophisticated in their design and executions, specifically the installation of mechanical and electrical systems that were more and more being installed to recognized standards set by the American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC) and National Marine Manufacturers Association (NMMA). I’m not sure we could call this the golden age of fiberglass production boat building, but it is certainly mighty close.

Rob Mazza is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. He began his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, working for Cuthbertson & Cassian. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new, and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com