Istvan Kopar’s choice for the solo nonstop race around the world

Issue 124: Jan/Feb 2019

When he heard about the Golden Globe Race 2018 (see “Sailing Back in Time,” July 2018), Istvan Kopar had just turned 60. He signed up immediately because, despite his having two circumnavigations under his belt, going solo and nonstop remained on his bucket list. Adding to its allure, the Golden Globe Race (GGR) was not only a solo nonstop race, it had a twist that appealed to Istvan’s old-fashioned aesthetic: racers would be limited to sailing boats designed before 1982 and using only technology that existed in 1968 — no GPS, watermakers, satellite communications, or a host of other accessories and innovations sailors take for granted today.

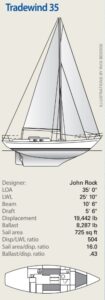

To secure his entry, and to get a head start on preparing for the race, Istvan needed a boat. He settled on a Tradewind 35, because it was among the first of the few boats approved by the organizers of the GGR and there was one for sale at the right price just three and a half hours from the boatyard where he planned to do his refit.

Designed in the early 1970s by UK boatbuilder and designer John Rock, the Tradewind 35 is not widely known in the US, and seems an unlikely choice of boat for an American. Yet it has a familiar look to it, perhaps because it is typical of its time, with long overhangs and a full keel with the rudder attached. About 70 are estimated to have been built, first in the UK and later in the Netherlands.

Weighing in at 19,442 pounds, the Tradewind 35 has a displacement/length ratio of 504, which is high even for boats of its type and era. In a race that prioritizes survival over speed, Istvan reasoned that a heavier boat might prove to be an advantage. It will be speedy in anything over 20 knots of wind, and the sail area/displacement ratio of 16.0 indicates that it has adequate sail power for lighter winds.

But a production sailboat, however stout and heavy — especially one that rolled off the line more than three decades ago — isn’t necessarily ready to sail around the world nonstop. And this particular boat, Puffin, didn’t seem destined to spend her golden years being raced through the Southern Ocean by a bombastic Hungarian-born Floridian. She was accustomed to sun-soaked weekend-afternoon sails on placid Lake Champlain. Istvan had work to do.

Three years on, Puffin, docked at the Golden Globe Race village in Les Sables d’Olonne, France, was unrecognizable from her former self. She was now a glossy orange good old racing machine, the number 37 emblazoned in white on her sides. She cut a fine figure; only her lines belying her age. She has just the slightest tumblehome paunch, perhaps a vestige of her former sundowner days.

The grand tour

A week before the start, Istvan greeted me with a vigorous handshake as he invited me aboard for a tour of Puffin’s transformation, which had consumed the previous three years of his life and finances. (Just one year prior, race officials documenting racers’ preparations wrote this about Istvan: “He has removed his wristwatch, not just because it is an obstacle at times, but to stop himself from checking off the days like minutes. There is just one year to the start, and Puffin is still half-naked.”) We started at the bow.

“I added reinforcement at the lower section of the bowsprit,” Istvan said. Upon buying the boat he noticed that freezing water had opened up the bowsprit’s stainless steel tubing. “I realized the tubing was light and needed reinforcement. We made a new bobstay with larger-sized wire and a turnbuckle to match, then replaced the chainplate, so everything got beefed up.”

We stepped aft a few paces and Istvan conspiratorially showed me what he termed a “Puffin special feature.” Before me were two inner forestays, side by side. “This is unique, you won’t see this on any of the other raceboats,” he said. “This setup worked very well for me on my first solo circumnavigation, as it allowed me to hoist two identical sails wing and wing, a kind of butterfly setup. The other benefit is that it allows me to put my storm jib in standby mode.”

Istvan hurried me over to the mast. “I may also be the only boat in the fleet who kept all the control lines around the mast.”

Recognizing this as one of the great philosophical debates in sailing, and certainly in this race, I asked Istvan to explain his choice. “I firmly believe that when lines are led to the cockpit there’s a greater chance that they will get tangled someplace,” he said. “On the other hand, this is far more demanding; I need to dress up every time I leave the shelter of the dodger. If everything works fine and their lines stay untangled, those guys [who led their lines aft] will have an advantage. But in my experience, lines and blocks do become tangled and that creates more problems.”

Istvan pointed to an orange sail wrapped in a blue sock at the base of his new Selden mast. “I always keep the trysail here, always on standby. At one of the boat shows I was given this demo spinnaker sock, so I just hid my trysail in this sock. The big benefit is that I can tie it to the handrail and it’s not in my way.”

Showing me one of Puffin’s hatches, Istvan said, “I was planning to replace the glass on all the hatches, but the budget didn’t allow me to do that. Because seamanship is anticipation, preparing for the worst, I cut canvas covers the same size as the hatches to use to stem water ingress should the glass break. It’s a temporary solution, but at least I’ll avoid a sinking situation.”

A pained expression passed across Istvan’s face as he regarded the cabintop. “I painted Puffin’s hull safety-orange, figuring that would satisfy the race rule that there be 2 square meters of orange on deck. But they were very clear that I wasn’t exempted, no way. So,” he said, pointing at the swath of orange paint on Puffin’s cabintop, “yesterday we did this. It was like butchering, very quick. Unfortunately, we made Puffin ugly.”

From the cockpit, Istvan showed me how he’d moved the traveler track from forward of the helm to forward of the dodger. Where the traveler had been, he added a large locker for additional propane storage. This made the cockpit well smaller and, with the addition of two cockpit drains, better able to drain quickly in the event of a pooping or a knockdown. (I could appreciate this change, as I had sailed with Kevin Farebrother, another competitor, from Falmouth to Les Sables d’Olonne on his Tradewind 35. Although I enjoyed the comfort of the roomier cockpit, it drained slowly, and I had a cold footbath for the duration of our three-day passage.)

Istvan highlighted the importance of the line bags he’d added. “I put a couple of bags here because the lines, in heavy weather, they have the tendency to leave the cockpit.” He also installed a new Lexan companionway dropboard, because he wants to see what’s happening outside when he’s below, and fitted several attachment points around the cockpit for his safety tether.

Istvan then showed me something that wasn’t new. “This compass is a unique piece,” he told me with obvious pride. “It was aboard Salammbo, the boat on which I made my first solo circumnavigation. I sailed 60,000 miles with this compass. It’s an old friend.” Istvan was referring to his 1990–91 solo one-stop circumnavigation in his self-built 31-footer, which he accomplished without GPS, autopilot, radar, watermaker, or a heating device.

Acknowledging he’s not the same sailor he was in 1990, Istvan has outfitted Puffin with what he affectionately termed “age-related aids.” “I am seemingly an old guy, 65. It’s not a secret, so I need a granny bar,” he said, pointing to the mast pulpit he’d use for support while reefing. He’d also welded a grab bar to his dodger frame and fitted stainless steel handrails to the cabintop. “The unique thing with those handrails is that they have their interior counterparts that I can grab when I am inside.”

Structural reinforcements

With no complex electronics to install, Istvan focused on refining and strengthening Puffin’s systems. Down below, he showed me what he did for her chainplates. “The original chainplates were deck-mounted, with only a backing plate under the deck, nothing else,” he said. “So I created this to distribute the load from the shrouds.” He showed me a cable that ties the underside of the backing plate to a point on the bulkhead where it meets the hull.

Istvan then directed me toward the head to inspect the compression post beneath the deck-stepped mast. During the refit, when the old mast had been taken out, Istvan removed the head door. “The race organizer was very stubborn that I had to reinstall the door, which is nonsense for a solo sailor. Who needs the privacy? But it turns out that this was a lifesaver for me. When I put the door back on, after a sea trial I couldn’t close it. That’s how I noticed that the deck was compressed forward of the mast.” Istvan’s solution is a custom aluminum bracket that ties an area just forward of the mast (the head doorframe) to the compression post. “Installing it took me four days of constant cursing.”

Accommodations

Istvan is not one to do things by half measures, so when it came to his living space, rather than use LED lights (which are one of the few anachronistic race-approved items), he stuck to his retro sensibilities. He pointed to his oil lamps. “I’m an old-fashioned guy. I have old-fashioned lighting.”

The galley was what you might expect: a two-burner stove (he’d removed the oven) and a freshwater foot pump (he’d added a tank to give him 100 gallons of capacity). But he was most excited to show me a custom shelf a friend in Canada had built that could be transformed into a chart table. “So I clear my stovetop, fold this down, and create a really big table for serious chart work,” he said, while flipping open the contraption to demonstrate. “You see, everything is for practicality.”

extended, covers the galley stove and

adjacent furniture to give Istvan a large flat

surface on which he can lay out a paper

chart, the only kind permitted in the GGR.

Affixed to a bulkhead, smack-dab in the middle of the saloon, was a latched wooden box. From it, Istvan retrieved a plastic sextant. “A sextant is fragile, and you don’t want to damage it before you finish,” he said. Stowed nearby was another box that houses a beautiful Wempe chronometer (electronic watches are prohibited in the GGR). “This is really something,” Istvan said, leaning back to admire it. “If I am lucky enough to finish the race, we’ll auction it off for a really good charity.”

At the forward bulkhead, Istvan showed me his stowable workshop. “It’s a unique workbench with two working vises. The beauty of this thing is that I can just remove the securing pins and relocate it, including to the cockpit.”

where he needs it, including in the cockpit.

Performance under way

I asked Istvan how he thought Puffin would fare against the other boats. “There is no handicap in this race,” he said. “While the Tradewind is a good solid design, it’s a very beamy boat. Puffin is a very telling name because her shape is like a little puffin! The Rustler 36 [six of them started in the race] will probably beat me in a light and moderate breeze. My only hope is to catch up in heavy weather.”

When sailing with Kevin Farebrother (unfortunately, Kevin retired early in the race), I found the Tradewind 35 tracked well, and it responded quickly when an overly eager GGR fan, keen to take photos, came within a couple of feet of hitting us. When the winds picked up, the boat seemed to sit back and dig in, easily plowing through the choppy waters of the English Channel. Her heavy displacement and broad beam allowed for a capacious cockpit and plenty of headroom below, important comforts for a sailor expecting to spend 250 or more days at sea.

Conclusion

Unlike boats used in modern races such as the Vendée Globe, where competitive entries cost $10 to $15 million, the GGR designs can be picked up for bargain-basement prices. On Yachtworld.com, at the time of this writing, three Tradewind 35s were listed from $47,000 to $67,000, four Rustler 36s from $79,000 to $121,000, and a Biscay 36 for $47,000. Any one of these vessels would make a nice GGR 2018 souvenir (though you’d have to travel to the UK to get one). However, anyone wanting to race in the GGR 2022 would be looking at spending $100,000 to $300,000 on improvements.

Istvan estimates that, sponsorships aside, he’s invested $100,000 or more of his own money and more than 2,000 man-hours preparing Puffin for the Golden Globe Race.

Fiona McGlynn, a Good Old Boat contributing editor, recently cruised from Canada to Australia. This past summer, she was at the start line in France, reporting on the 2018 Golden Globe Race. Fiona also runs WaterborneMag.com, a site dedicated to millennial sailing culture.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com