. . . and similar, but older, full-keelers

Issue 122: Sept/Oct 2018

Analyzing the performance characteristics of the Cape Dory 30 Mk II presents a bit of a challenge. When you look at the boat from above the waterline, you see a configuration that fits well with its 1986 contemporaries. That is, shorter overhangs and a long waterline for its 30-foot LOA, a rig with a large foretriangle and a smaller main with a higher aspect ratio that shows International Offshore Rule (IOR) influence, and an interior layout that’s quite roomy for a 30-footer and includes a generous shower area in an especially large enclosed head. However, below the waterline, you see a hull form with a full keel and attached rudder that is more typical of boats of 20 to 30 years before, not the more performance-oriented separate keel and rudder of its contemporaries. Indeed, in the mid-’80s, even designers of cruising boats, such as the C&C Landfalls, were doing their best to cut away the deadwood between the keel and rudder to reduce wetted surface and improve maneuverability. Ted Brewer’s “Brewer’s bite” is a modest example. Cape Dory, though, under the unswerving influence of its original designer, Carl Alberg, maintained the full-keel configuration throughout its long history, and never deviated from it.

I should also point out that fiberglass boatbuilders were more than willing to abandon the full keel because of the difficulty of laminating down into a deep sump, especially at the narrower trailing edge where the rudder attached, not to mention the challenges of laminating around the propeller aperture. In some cases this could only be achieved with split molds. The simple canoe body with a bolted-on fin keel and free-standing cantilevered rudder was much easier to lay up. After Carl Alberg’s retirement and his subsequent death in the same year that the Cape Dory 30 Mk II entered the market, Cape Dory remained loyal to this “traditional” hull form, even under the guidance of its new English designer, Clive Dent, who joined the company in 1983. Dent had apprenticed in the Camper & Nicholsons design office in England before moving to the US to work for Dick Carter. His first project for Cape Dory was actually a 30-foot motorsailer, which premiered a year before the Cape Dory 30 Mk II.

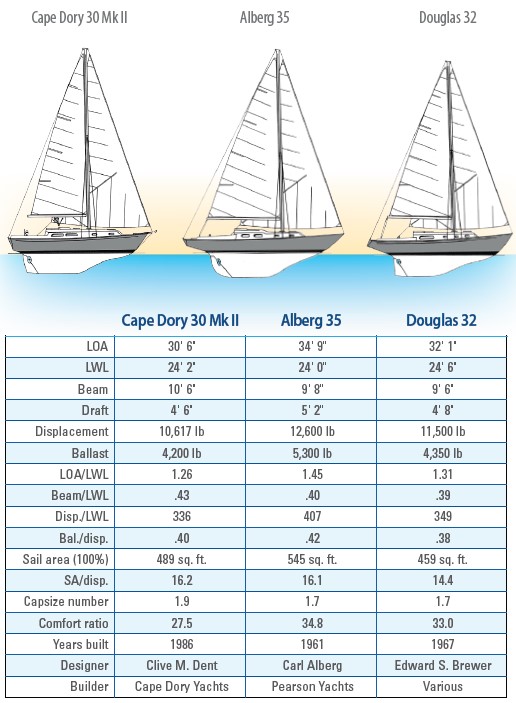

To find other full-keel production boats to compare to the Cape Dory, we have to go back to the early and mid-’60s. The 1961 Pearson-built Alberg 35 is a logical choice, since it was Alberg who established the Cape Dory design philosophy. The Douglas 32, introduced originally in 1967 by Ted Brewer, is also typical of the breed and stayed in production for many years under a variety of different builders. It started life as the Douglas 31, but was lengthened a foot by raking the transom to give it a more modern profile. Some of the early raked transoms were created by chopping off, or “bobbing,” the longer overhangs of older CCA or Metre-boat designs.

Note that all three boats are within 6 inches of each other in waterline length, even though their LOAs differ by more than 4 feet. This shorter length often presented a marketing problem when selling boats by length, since weight really had a greater influence on cost.

The more “modern” Cape Dory has the lightest displacement and the lowest displacement/LWL (D/L) ratio of a still-conservative 336, although the Douglas at 349 is not far behind. The Alberg’s hefty D/L of 407 reflects the heaviest displacement on the shortest LWL. The power-to-weight ratio, as expressed in the sail area/displacement ratio (SA/D), shows the Cape Dory and the Alberg at a respectable 16, while the Douglas is a tad underpowered at 14.4.

The most notable change in design philosophy from the 1960s to the 1980s can be seen in the substantial 1-foot increase in beam on the Cape Dory, which not only reflects the influence of the IOR, but also is helpful in achieving that improved interior volume mentioned above. The increase in beam also contributes to an increase in stability. Even with that greater beam, due to her moderate displacement, the Cape Dory still has a suitable capsize number of 1.9 which, being under 2, is acceptable. The narrower beams and heavier displacements of the Alberg and Douglas produce a capsize number of 1.7, a figure not often found in boats of this size.

The heavier, longer, and narrower Alberg and Douglas have a more comfortable motion, as reflected in their comfort ratios in the mid-30s. The Cape Dory’s at 28 is still quite reasonable for a boat of this size.

The more modern Cape Dory is the only one of the three to incorporate a bowsprit. With the headsail tacked well aft, the sprit’s real purpose seems to be more associated with anchor storage and retrieval than greatly extending the foretriangle, although that might have changed with the optional cutter rig.

In the Cape Dory 30 Mk II we see a builder adhering to an older design tradition, while at the same time trying to incorporate more modern design features to make its product marketable against its competitors and even its own older product. I’d say Cape Dory pulled it off pretty well.

Rob Mazza is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. He set out on his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, working for Cuthbertson & Cassian. He’s been familiar with today’s good old boats from the time they were new, and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com