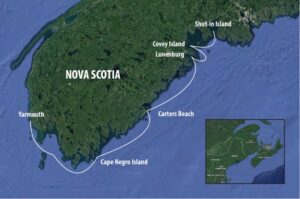

A meander along Nova Scotia’s southwestern coast is just the ticket for a miles-weary sailor.

Issue 130: Jan/Feb 2020

Straws and camel’s backs are funny things. I’d been sailing with my husband and our young son and daughter on our 1990 Australian-built Adams 45, Osprey, full-time for more than four years when the straw landed on my back during a short, easy day sail from Block Island, Rhode Island, to the Elizabeth Islands in Massachusetts. Suddenly, I didn’t want to do it anymore. I was bone-tired of moving. Which, because moving is what we did, was a problem.

And we were traveling with two other boats, all of us friends, all on the way to Nova Scotia, until I dug my feet disconsolately into the Massachusetts sand.

And we were traveling with two other boats, all of us friends, all on the way to Nova Scotia, until I dug my feet disconsolately into the Massachusetts sand.

“We’ll go slow,” my husband, Johnny, said to me. “We’ll just take it one day at a time.” Which is how we ended up day-hopping from Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, around the southwestern coast on our way to Halifax. And unlike so many sailors who hurry to Halifax, the Bras d’Or lakes, or points further north and bypass much of this coast, we ended up in some of the most memorable islands and beaches we’d seen in four-plus years of memorable islands and beaches.

We started in Yarmouth, where as soon as we’d tied up to clear customs, we met Bob and Isabel, both from Ottawa, who had moved here many years ago. They kept a Mirage 24 on the nearby Chebogue River, and like pretty much every local we met in Nova Scotia, they were generous, outgoing, and knowledgeable. Bob offered us a ride to a bookstore and a grocery store, and he gave us some charts, sailing directions, and the all-important local knowledge for navigating the Schooner Passage in the Tusket Islands.

“It’ll cut about 10 miles off the trip, since you don’t have to go all the way out and around Seal Island,” he told us. “But you want to get there at just about slack high water.” Trying the passage against the current would be folly and potentially dangerous, with water moving up to 4 knots when the tide is running.

We left Yarmouth in a grey drizzle and traveled about 12 miles south to Murder Island, the entrance to the passage. (Ah, the place names here: Devastation Shoal. Little Hope Island. Cape Salvages. Roaring Bull Rock. Bastard Rock. Coffin Island.)

We had good visibility, and the current wasn’t bad. We sailed by small enclaves as if they were on the ends of the earth, so remote that each reminded me of an Inuit village. Instead of ice, they perched on rocky islands, some covered with a thick bedding of peat in which fir trees managed to take root and thrive. We passed a lighthouse on the tip of Pease Island that was probably the most despondent looking place I’d seen; the clapboard house itself had probably once been quite beautiful, but now sheep wandered in and out of the rooms.

Once through the passage, we crossed Lobster Bay to round Cape Sable Island, the southernmost tip of Nova Scotia. Here thick fog descended, and the tidal currents came alive. We couldn’t see much beyond two boat lengths and the water all around us moved and swirled, upwelled and boiled. It was like being in the Gulf Stream, minus the warmth and sunshine, and, thankfully, the waves. The seas here were benign, a little rolly, but that was all (and all we wanted). The chart was covered with the little symbol that indicates tide rips, as well as breaking waves in a heavy sea.

Around Cape Sable Island and up along the southwest coast, we came to our first stop, pulling into East Cove at Cape Negro Island. The fog was so thick that we didn’t see the island until we were right on top of it. I wondered aloud how sailors navigated these waters without chart plotters and GPS; Johnny pointed out that they ran aground and sank. A lot.

Then the fog cleared, and we were in awe. Though called by the singular, the island is really two round, high land masses—known locally as North and South islands—joined in the middle by a causeway of rocks shaped much like a sand dune; it was near this feature that we had settled in a small bay. At its lowest point, the causeway went underwater at high tide and the island briefly became twins. The “dune” was steep and sharp, clearly shaped by the waves, but comprised wholly of rocks of varying siz¬es. All of them were rounded, sea-worn quartz and granite from a foot across to the size of an egg.

We had to explore. The island was home mainly to sheep, and obviously a shepherd who must come and go. We found a tidy little camp with two cooking fire pits and pots and pans tucked away safely under some boards. The ruins of an old house on a hill, facing southwest, were accompanied by a fallen stone wall that framed two sides of the house’s yard. Between the beach and the ruined house, a bog was filled with iris and other flowers; the hillsides were covered with whatever thatch of grass the sheep had left, as well as thistles and other wildflowers.

Thick forests of fir trees clustered throughout, and we found freshwater springs dribbling water down the hills and onto the beach. A trek around the northeast side of the island brought us to the octagonal stone foundation of an early lighthouse, the first built in 1872 and the second in 1886. By 1915, a new light¬house was built on the island’s southeast end, where it was deemed more useful. In 2009, it was listed on the Canadian Register of Historic Places. According to lighthousefriends.com, it was deemed historically valuable for its architecture as well as its cultural significance, as noted in the Heritage Character Statement:

“The lighthouse is significant for the community because of its association with the Perry Family. Freeland Perry, fisherman and the island’s barber, was the light keeper between 1916 and 1943. His son-in-law, Harry Perry, one of the two violin players for the island dances, served as the light keeper between 1943 and 1963. The lighthouse is also a very good example to illustrate a significant phase of the community. It was built in response to the changes of technologies that permitted fishermen to travel further to the fishing grounds.”

Remote and silent, save for the occasional bleating sheep, crying gull, and curling wave, Cape Negro Island seemed otherworldly, like a fragment of Ireland that had drifted west and fetched up on Canada’s shores. We clambered over massive boulders evidently dropped here by giants, walked thin threads of sheep tracks, and didn’t see another soul. It was so compelling a place that, two weeks later, we returned here on our way south.

But for now, we were headed north. I was looking for a decent anchorage somewhere halfway between Cape Negro and Lunenburg to cut that 84-mle trip into two. On the chart near Port Mouton, I came upon a pretty little horseshoe behind Mouton Island, and right there it said, “prominent dunes,” and gave the name of Carter Beach and another long beach. Huh. Beaches. We could use that sort of thing.

So, in the company of our friends aboard the two other boats, we motored through thick fog all day, staying about a quarter mile apart and running on instruments. Carl Sandberg didn’t quite cover the bases when it comes to fog here. There was nothing feline about this fog. This fog came in like a Zamboni. It was like sailing inside a sweatshirt.

It started making us punchy, and for about 10 minutes, Sam on Chére and Johnny yakked on the VHF about the latest great scheme, a coffee table book titled Fog. They worked out a whole marketing plan, including bottled fog, eau du fog, hoody sweatshirts with no hole for the face so you could experience the fog. We were going to self-publish and sell the movie rights.

When we finally turned inshore, around Mouton Island, we simply drove out of it. While the fogbank sat offshore, we entered a completely different climate, season, universe. It was like waking up and starting the day over again. Off came the seaboots, jeans, fleeces, and foulie jackets. By the time we were anchored in front of a gorgeous, long white beach, I was in shorts and a bikini top.

We were in the dinghies in an instant. The water was still dark, but it was clear enough that we could make out the depth contours as we approached the beach, and we could see the bottom at 10 feet or more. I had never expected to see white sand beaches in Nova Scotia, but Carter Beach was stunning. The sand was fine and glimmering and stretched for a couple miles. Behind it was a thick dune, covered in tall green grass, and behind that, a sandy hillside and then woods dense with fir trees. Here and there, at either end of the beach, huge granite boulders framed the whole picture.

A couple dozen people walked the beach, hanging out, sunning, walking dogs. It was glorious to be back in bathing suits and feeling the warm sun. Maya, our Panamanian rescue dog, dug and rolled and generally went crackerdog in the sand, happy it wasn’t another rocky Maine coast. We walked up into the woods and back dunes and found apple trees, flowers, and freshwater springs that trickled all the way down to the beach, where the kids swam, or, rather, they ran into the water, screamed like mad, and then ran out, repeatedly.

That night, a full moon rose and under its silver light, we all shared dinner in Chére’s cockpit. Then, by 10 p.m. or so, the Zamboni rolled in and all we could see were pinpricks of light at the tops of our masts.

The next day we were off to Lunenburg, a destination worthy of its own story. While there, some local sailors told us about two more islands we couldn’t miss on the way to Halifax.

The first, Covey Island, was not far from Lunenburg as the crow flies, but as Osprey flew, we had to make a long loop and around East Point Ledge and the myriad rocks, ledges, and islands that characterize this peninsula, past the Upper Rackets and Hell Rackets (more names to love) finally turning back westward to reach Covey Island.

Covey was like two cherries connected by a low stem of rock, marsh, peat, and tall grass, with a gorgeous pond right in the middle. A pebbly brown beach ran along the leeward side of the stem, arced in a half-moon. On either end the island rose up into tall, thick forests of firs and birches whose leaves fluttered and sang in the late afternoon breeze.

Thanks to the pond, we saw for the first time in a while actual shore birds that looked like a type of plover, as well as dabbling ducks and diving ducks. There were ravens and crows, ospreys, herons, and goldfinches flitting back and forth over the marsh and pond into the forest. Many ecosystems mingled there, which made it a far more interesting island in that regard than some of the other, rockier ones we’d been exploring.

But those had had their own fascination, too, especially geologically. The rock formations were thickly sedimentary, so that we could see how the glaciers laid out this whole place. Much of it was shale, which we would smack with another rock and split straight down the middle and then again—a good way to find fossils, we’d heard. We’d seen lots of different minerals too; the deep red of iron, the bright blue-green of copper. Cruising this coast would be a geologist’s dream.

After a day exploring Covey, we left in the morning with the call of a loon seeing us off. Our next stop was another island we never would have known about had it not been for a local telling us not to miss it: Shut-in Island in St. Margaret’s Bay. It stood high and rocky, just off the mainland on the bay’s northern side, yet a world apart. We anchored behind it near Otter Cove and dinghied to a small landing area, from which a trail led inward.

We walked up through fir forest made magical by tiny red toadstools and white, lace-like mosses patched amid the thicker, softer green mosses and palm prints of lichen. The morning’s thin scrim of fog had dispersed by the time we had anchored, and now, gaining the island’s broad top, the sky was a robin’s-egg blue dome above us.

We hiked over grey whalebacks of granite to take in views that stretched for miles up and down the bay. Immense boulders here and there provided irresistible rock-scrambling to perch even higher. Best of all, everywhere between the rocks were lowbush blueberries in full, glorious fruit. We crawled around like hungry bears plucking berries and gathering them into whatever we had, mostly our mouths and our water bottles.

As on Cape Negro Island, we saw no one, seeming to have this astonishing place all to ourselves. From here, we would go on to the beautiful city of Halifax, landing right in the middle of its famous Busker Festival. But for now—sated with blueberries and unforgettable beauty—I was inwardly thanking that last straw that had brought us this way.

Wendy Mitman Clarke, Good Old Boat’s senior editor, is a lifelong sailor, award-winning writer, and published poet. You can see more of her work at wendymitmanclarke.com.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com