…And Two More Cruising-Capable Performance Tris

Issue 130: Jan/Feb 2020

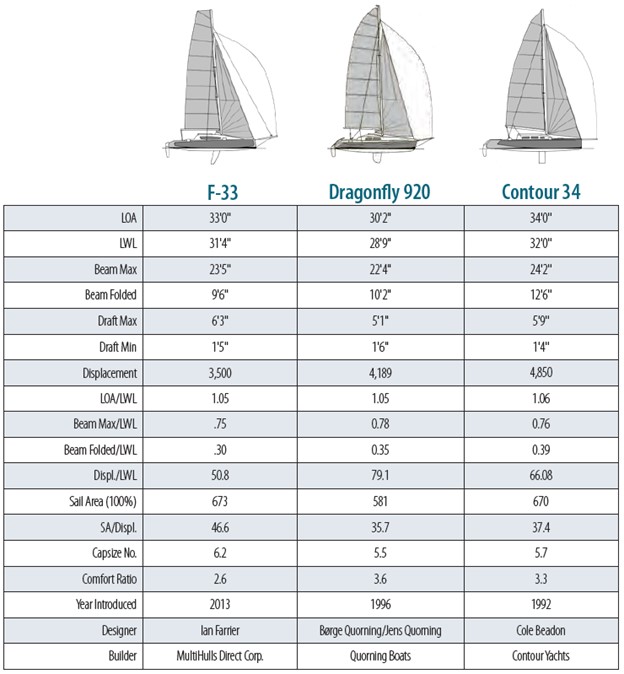

It’s probably fair to say that the average recreational sailor seldom considers a performance trimaran for extended or even short-term cruising. This is too bad, because each of these three trimarans—the F-33, Dragonfly 920, and Contour 34—manages to combine the exhilaration, speed, and relative handling ease of high performance with reasonable accommodations that qualify them as possible cruising options.

Right up front, each manages to overcome the greatest disadvantage of multihulls when it comes to boat dockage and hauling, a wide beam. The Danish-designed Dragonfly was my first exposure to the folding trimaran concept. Introduced in 1996 as a cruising performance trimaran, these boats employ the Swing Wing, which hinges the amas horizontally, that is, swings them aft so they rotate against the main hull to reduce beam by more than 50 percent (in less than a minute per side, according to the company’s website).

I was further exposed to the folding concept by Paul Countouris at Contour Yachts, when I did some mast development design work for the Contour 30 in the ’90s. Designed by Cole Beadon, the Contour 34 was an evolution of his Contour 30. His goal was to maximize the trailerable trimaran concept and modify the amas’ design to resist the potential for pitchpoling. All tris are designed to transfer their sailing buoyancy to the leeward ama as the boat heels, allowing enough reserve buoyancy in the ama to support the boat’s entire weight. At this point, though, the ama can bury its bow and, in the worst case, cause the boat to pitchpole. Beadon, as he related to Bob Perry, designed the 34’s amas to shift the center of buoyancy forward as the amas become further immersed, helping resist this potentially calamitous situation. In that respect, as much design time is devoted to the shape of the amas as to the shape of the main hull.

To increase stability when folded, the Contour deliberately forces the amas down into the water as they swing aft, transferring more weight to the amas. Unlike the Dragonfly and the Contour, the F-33 uses the Farrier Folding System, which hinges or “rolls” the amas vertically, tucking them towards and adjacent to the main hull with hinged linkages. The F-33’s folding system achieves the greatest reduction in beam of the three boats.

Each of these boats features rotating masts stepped on deck, relying on jumper-type stays to keep the mast in column. Each employs a fully battened main with large roach and a small fractionally rigged jib that is easily tacked, or even self-tacking. Each also sports a bowsprit to fly an asymmetrical spinnaker, helpful because tacking downwind is preferable to running dead downwind, due to the greater apparent wind speed achieved.

With displacement/length ratios all well below 100 and sail area/displacement ratios all in the 30s and 40s, all will be faster than monohulls of similar length and perform upwind nearly as well, although they may not point as high. Increased apparent wind does have some disadvantages!

It’s difficult to define accurate displacement figures for these boats, which don’t have ballast and should always be sailed light for optimal performance. Published displacements are generally in a “half-load” sailing condition, which includes the weight of crew, stores, and half tanks, etc. In a 10,000- or 20,000-pound monohull, variations in half-load displacement don’t make a radical difference in ratios where displacement is a factor, since 35 to 50 percent of the boat’s weight is consumed in fixed ballast. However, in a lightweight trimaran with no ballast, these variations can have a marked effect on the ratios.

Similarly, comparisons of capsize and comfort numbers aren’t easy because these numbers were derived from and for monohulls. And while a capsized multihull will remain inverted, most are difficult to capsize. They are more prone to pitchpole by digging an ama into a wave at speed, thus the emphasis on trying to prevent that with the shift of volume forward with heel angle.

Likewise, the comfort ratio is an attempt to quantify the relative motion of a boat in a seaway and, again, is based on displacement (heavy is better), beam (narrow is better), and a combination of overall and waterline length that takes into account the amount of overhang (overhangs are good). While ratios in the low to middle 30s are preferable, all three of these trimarans fall in a range between 2.5 and 3.5! Yet, there is no denying that with their flat heel angles and great speed potential, these three trimarans seem comfortable to sail, even at speed.

It may require some rethinking about how you want to sail, but none of these trimarans should be overlooked as cruising choices simply because they emphasize performance and have three hulls, not one or two.

Rob Mazza is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. He set out on his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, when he began working for Cuthbertson & Cassian. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com