A diver’s insight can reveal the hull story

Issue 128: Sept/Oct 2019

As I eat oatmeal and berries for breakfast, I make the day’s schedule. The oatmeal will be the last food I have until late afternoon because, in my line of work, I spend much of my day on my back, sometimes even completely upside down, feet-up. Too much food and I get an upset stomach, an acid-reflux thing.

From my daily check of the NOAA forecast, I learn that the skies are going to start overcast, like a lot of days in Oxnard. Yet the clouds are likely to burn off midmorning and they expect to issue a small-craft advisory in the afternoon. The sea temperature is 57 degrees; I fill three used juice bottles with piping-hot water and stick them in my cooler. They’ll remain hot long enough for me to pour them into my wetsuit later, just about the time I am cold enough to think about quitting. Hot water keeps me going.

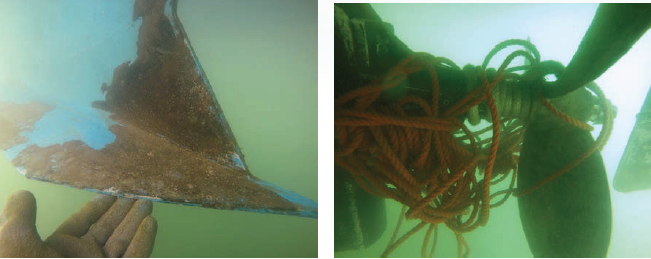

When people ask about my work, I tell them I’m a diver, that I clean and maintain boat bottoms. This regularly involves scraping barnacles off hulls, but I’m responsible for much more. I’m my clients’ eyes below the waterline. I let them know about problems I see, such as worn paint due for a new coat, or the new coat the yard applied last month that’s not adhering to a large area aft, flaking off in big pieces. I can spot osmotic blisters when they’re tiny and track them over time, to let the boat owner know if they’re growing in size and number. I can see the earliest telltale signs of electrolysis on a prop or shaft. It’s obvious to me when a particular boat or slip is “hot” and zinc anodes are being eaten up more quickly than on surrounding boats. Sometimes, I’ll report newly dinged or chipped props, or remove lines or netting that have become wrapped around a prop or a shaft.

In the past, I would verbally report problems to my clients. Today, I can email photos or video I’ve taken underwater so clients can see things for themselves. This technology has been a positive change in the industry, even helping to weed out dishonest business practices and improve the overall quality of work.

The first boat that I have scheduled for the day belongs to a new customer and has reportedly not been cleaned in four months. As I pull my skiff up to the dock, it looks to me like it hasn’t been cleaned in a year, judging by the size of the mussels clumped around the rudder. I try to get the harder jobs done earlier in the day so the rest of the day seems easier.

Before rolling backwards into the water to start cleaning, I’ll pull my hood over my head and don my fins, gloves, and mask. I’ll pull the cord to start the Honda motor that powers my compressor and note that all 100 feet of my hookah hose is coiled just so, in a way that ensures it will follow me tangle-free as I do my job.

If I later need a coarser brush or a particular tool or a 1 ¼-inch collar zinc, it’ll be right where I expect when I reach for it over the side from the water. Regulator in my mouth, I fall backwards with a window-glazer’s suction cup in my left hand and a scraper in the other. I orient myself as the cold saltwater quickly finds a path to trickle down from my neck to the small of my back. The shock is my daily motivation to get moving in a bid to stay warm.

After scraping the bulk of the growth off the bottom, I notice that I am surrounded by thousands of tiny bait fish, all enjoying a free meal in the cloud of sea life I created.

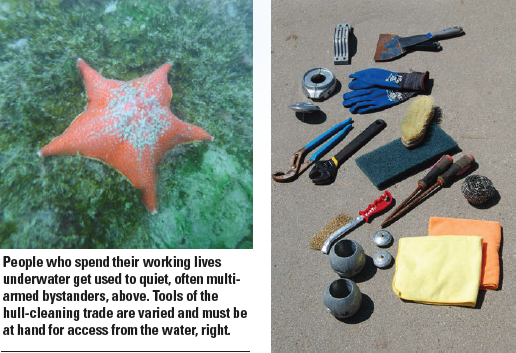

People regularly ask me if there is, “anything to see” in the harbor. Absolutely! On any random day, I observe spider crabs scooting through the sea stars and scallops that are stuck to the dock pylons. Jellyfish, nudi-branchs, lobster, and rays all call the harbor their home. And then there are the octopuses! I often find them resting wrapped around a prop or inside a through-hull. It is always amusing to shoo them away, as I always get inked.

After two-and-a-half hours spent under the neglected boat with a scraper, steel wool, a stiff plastic-bristled brush, a wire brush, a scouring pad, and a screwdriver, I motor off to the first of five or six boats that I clean on a monthly basis. These will fill the rest of my day. They’ll be a mix of sail and power, from a 22-foot Catalina to a 47-foot Hatteras with twin screws, twin rudders, and trim tabs with hard-to-clean actuators. In addition to removing all the soft growth on the hulls, I’ll change a zinc or two, ream hard growth out of through-hulls, and clean stainless steel shafts and bronze props until they’re smooth and shiny. I’ll be as careful as possible to remove tenacious growth and scum from the unpainted waterline of one, without getting too abrasive on the exposed gelcoat.

Finished, I’ll arrive back at the dock exhausted, cold, and hungry, but happy. A typical day is satisfying, another group of hulls is clean and anode-protected. My skiff is organized and prepped for the next day. If I’m lucky, I’ll bring an underwater story home for my kids; spotting a ray or small shark is always a hit. At home I’ll send the day’s bills and reports via email, including a few before and after pictures. And each of those clients, no matter what I report, receives peace of mind from the information I send, clear knowledge of what is happening with their boat beneath the waterline.

On Becoming a Hull Cleaner

What kinds of people succeed in your trade and how do they get started? What was your path?

People in this line of work must love the water. They must have the integrity that drives them to do a thorough job on every boat, or they won’t last. It’s hard work; upper body muscles get a workout every day. It isn’t clean work; most days I’ll emerge from the water and my wetsuit is crawling with tiny krill (they get in my hair and ears too). It’s also not a social job, most of the days it’s just me and the underwater life. Even above water, it’s rare that a boat owner is there to talk to when I’m done; marinas are usually quiet places during the week, especially outside the summer months. Some divers go to commercial dive school and then find work as hull cleaners. I grew up surfing in Southern California and was certified as a diver in my mid-twenties. I advanced as a rescue diver and then worked as a dive instructor with local shops. I was turned on to hull cleaning as a more lucrative career option and worked for a large dive company before opening my own business.

Always the Unexpected —Michael Robertson

In my 20s, your editor worked for a couple years as a diver cleaning boat bottoms. As Brian would attest, as rote as each day might seem, each is very different; I never knew what might surprise me. I once picked up a plastic chair from the bottom to return to the dock. The biggest octopus I’d ever seen (or have seen since) flew out from underneath the chair, right in my direction, brushing over my mask. It scared the heck out of me. Then there was the Sunday morning my boss called, gave me the phone number of a guy who’d called her in a panic because he’d dropped his car keys off the dock. “It’s up to you whether you take the job, charge what you will, it’s your day off.”

I called the guy and asked if he could wait until the next day, explaining that it was a huge effort to pull on a full wetsuit and motor over just for one quick dive, “And there’s a chance I won’t find them, the bottom is very soft muck.”

“I’ll pay you $200 for trying.” I’d have spent a couple of days looking for his keys for $200. I was suited up and drove there as fast as possible.

“Hey look, I appreciate you coming. I didn’t drop my car keys.” The guy pulled out a badge. “I’m an FBI agent and I dropped my gun. It’s holstered, safety’s on.”

Visibility was terrible, but I found the gun within 5 seconds. I didn’t bring it to the surface, I couldn’t. For almost 20 minutes I swam around in slow circles and surveyed stuff growing on the pilings; I picked around the odd trash on the bottom. When I did surface with the gun, I saw color return to the agent’s face. Twenty-five years later, it’s obvious to me that the agent would have been much happier paying for a 1-minute recovery than a 20-minute recovery and all the anxiety that went with it. But at the time I thought it would be wrong to surface so quickly to take that much money.

Brian Mykytiuk has been maintaining boat bottoms underwater for 16 years. He and his wife, Lindy, own and operate Neptune Dive Service of Ventura, California. Between Channel Islands Harbor and Ventura Harbor, Neptune services over 150 boats monthly. When Brian’s not underwater, he enjoys spending time with his family at the beach, maintaining his garden, and perfecting his smoked tri-tip.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com