. . . and fellow CCA-to-IOR transition boats

Issue 126: May/June 2019

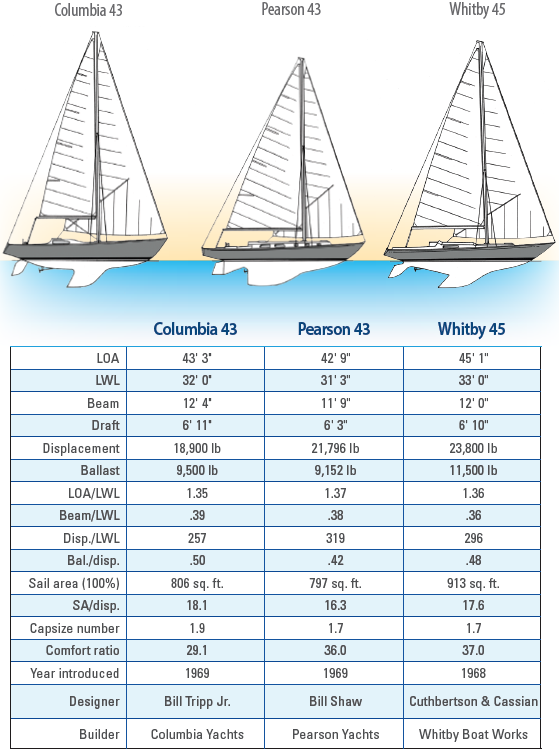

The late 1960s was a period of transition in the history of yachting, when fiberglass construction, combined with a secure and growing middle class with more leisure time, ushered in the New Age of Sail and the building of so many good old boats. It was also a period of transition in yacht design, when the North American- based Cruising Club of America (CCA) handicap rule gave way to the International Offshore Rule (IOR) that would become the norm in 1970. The “I” in IOR meant there was now a truly international rule for offshore racing, replacing the RORC rule in Britain and Europe and the CCA rule in North America. The Columbia 43, and the two comparison boats I have chosen, the Pearson 43 and Whitby 45, represent the last phases of the CCA rule and the early phase of larger fiberglass production sailboats.

The Whitby 45 is of interest for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that it’s an example of a Cuthbertson & Cassian design prior to the creation of C&C Yachts. A development of the Bruckmann-built Redline 41, the Whitby 45 was commissioned by Kurt Hansen, the owner of Whitby Boat Works, a company now better known for building the Alberg 30, Alberg 37, and the Ted Brewer-designed Whitby 42. At the time, the Whitby 45 was the largest boat the company built, and Hansen raced hull #1, Dushka, extensively, even in the SORC (Southern Ocean Racing Columbia 43 Pearson 43 Whitby 45 Conference). Whitby’s largest boat, the Ted Brewer-designed center-cockpit Whitby 55, was introduced in 1982.

This was also the period when the rudder was being separated from the keel, which itself became a distinct foil-shaped appendage. I have often cited the Cal 40 and Red Jacket as the harbingers of this design trend in North America, but it was Dick Carter’s victory in Rabbit in the 1965 Fastnet Race that led the charge in Europe. So it’s interesting to see the early swept- back fin keel on the Tripp-designed Columbia and, on the Whitby, the distinctly Cuthbertson & Cassian swept-back keel that characterized all C&Cs from the early ’70s. Both these boats also had free-standing cantilevered spade rudders, while on the Pearson, Bill Shaw took the more conservative but popular route of a substantial skeg forward of the rudder. This configura- tion was probably influenced by the rudder and keel configuration on the winning 1967 America’s Cup 12 Metre, Intrepid, where the skeg was an exten- sion of the upper end of the fin keel.

The other common elements of these last CCA designs are the long over- hangs, representing 36 to 39 percent of the boats’ overall lengths, the curving sweep of the profiles and sheerlines, and the relatively low freeboards of the Pearson and the Whitby.

The Columbia’s higher freeboard, which allowed greater interior volume and a predominantly flush deck, was also ahead of its time. This departure from the norms of the day was not considered attractive at the time, but it, too, was pointing the way to boats of the future. When I designed for Hunter in the early ’90s, Warren Luhrs would automatically raise the freeboard on any new design by at least 2 inches, solely to increase the interior volume and allow us to push more of the accommodation plan outboard.

The displacements of these boats are moderate by modern standards, but light for the period, especially that of the Columbia, which has a competitive displacement/length (D/L) ratio of 257, compared to those of the Whitby at 296 and the Pearson at a more conservative 319. The ballast/displace- ment (B/D) ratios are high: 50 percent for the Columbia, 48 percent for the Whitby, and 42 percent for the Pearson. All three boats also have relatively high sail area/displacement (SA/D) ratios, with the Columbia’s highest at 18.1, closely followed by the Whitby’s at 17.6 and the Pearson’s at 16.3.

These three boats also illustrate the transition in sail plans between the CCA and IOR rules. The IOR essentially adopted the hull-measurement procedures of the RORC rule and the sail-area measurements of the CCA rule, so it’s interesting to see the higher-aspect-ratio “ribbon” mainsail, which was to become the norm under IOR, make an early appearance on the Columbia. The Pearson and the Whitby have boom lengths more in keeping with other CCA boats of the period and earlier. Consequently, a markedly higher percentage of the Columbia’s sail area is devoted to jibs and spinnakers, giving us another glimpse into the IOR future.

The narrower beams and higher displacements of the Whitby and the Pearson give them both the very safe capsize number of 1.7, and even the Columbia’s, at 1.9, is under the threshold of 2.0.

With its lower D/L ratio and higher SA/D and B/D ratios, the Columbia certainly has the performance edge on the other two boats on paper, but when it comes to sheer beauty, for my eyes the sweeping lines and profile of the Whitby 45 are hard to beat. After all these years, it is still a pretty boat. However, the Columbia was more representative of what the immediate future held for yacht design.

Rob Mazza is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. He began his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, working for Cuthbertson & Cassian, and later worked for Mark Ellis and Hunter Marine. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new, and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com