A distinctive big, fast sloop from the giant of West Coast boatbuilders

Issue 126: May/June 2019

Craig Shaw’s search for a racing sailboat ended when he found a Columbia 43. That was 35 years ago. Though Craig is now more cruiser than racer, Adios still serves him well.

Craig and his father were looking for a boat they could race offshore and on the Columbia River near their home in Portland, Oregon. As soon as they bought Adios they started racing her hard. She was a regular in many classic Northwest races, including the Swiftsure, Bridge to Bridge, Oregon Offshore, Whidbey Island Race Week, Oregon Race Week, and the Pacific Cup, which sails from San Francisco to Hawaii. In the skillful hands of the Shaws, Adios proved a tough competitor, usually finishing in the top of her class. About two dozen awards cover one bulkhead on Adios, including one for first overall in the 1985 Oregon Offshore Race from Astoria, Oregon, to Victoria, B.C.

After Adios finished fourth in class in the 1988 Pacific Cup from San Francisco to Oahu, Craig’s parents spent a year cruising in Hawaii. The following June, Craig and a friend brought Adios back to Oregon. As they neared the coast, the boat was surfing at speeds up to 15.5 knots under only a small headsail.

In 1994, Craig’s father bought a Hunter 54. Craig bought Adios and began converting her from a highly competitive racer to a cruising boat. He rented out his home and moved aboard. “Once I did that,” he told me, “it was a lot harder to race the boat.”

Over the last decade, Adios has become a regular in the Baja Ha-Ha, a cruising rally, sponsored by the West Coast sailing magazine Latitude 38, that sets sail every October from San Diego to the Sea of Cortez. Craig, a professional yacht rigger, enjoys the break from the wet Northwest winters and occasionally helps out other cruising boats with their rigs during his winters in Mexico. He also pits Adios against other boats in regattas in Banderas Bay and Zihuatanejo.

History

Columbia Yachts was one of the first West Coast builders of fiberglass sailboats. Founded in 1960 as Glas Laminates, it made camper tops and shower stalls, and built its first sailboat, a 24-footer, in 1961. The company changed its name to Columbia Yachts the following year when it built its second boat, the Sparkman & Stephens-designed Columbia 29.

In 1965, Columbia hired William Tripp Jr. to design a 50-foot yacht. The resulting Columbia 50 was the largest production fiberglass sailboat then available in the United States, and marked the beginning of a productive relationship between Tripp and Columbia during which he designed more than 20 boats for Columbia and its sister company, Coronado Yachts. It ended when Tripp died in an auto accident in 1971 at age 51. (For more on the designer, see “The Legacy of Bill Tripp,” November 2011; for more on the builder, see “The History of Columbia Yachts,” May 2002.)

Design

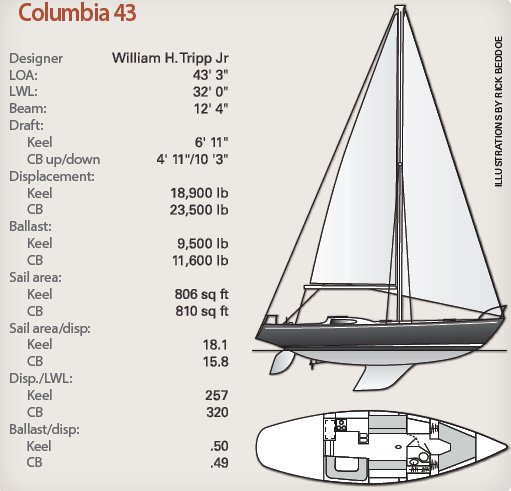

The Columbia 50 and Columbia 43 have some striking similarities. They have the same beam, 12 feet 4 inches, and the waterline of the 43 is only 15 inches shorter than that on the 50. The two boats are similar enough that hull #1 of the Columbia 43 had the same deck, house, and cockpit as a Columbia 50 — and it looked good! (The story is that it was a special request from a personal friend of Dick Valdes, Columbia’s president at the time.) At 18,900 pounds, 13,000 pounds lighter than the Columbia 50, the Columbia 43 was considered light-displacement in 1969. That and its hull shape enabled it to surf and compete effectively against the Cal 40, which dominated downwind offshore races of the day. This paid off in 1971 when Encore, a Columbia 43, placed first in class and 11th in fleet in the Transpac from San Pedro, California, to Honolulu, the West Coast’s premier yacht race. Racing wins were important to Columbia, which had about 40 percent of the auxiliary-sailboat market at the time. Even non-racers wanted a fast boat. One of Columbia’s advertising tactics was to tout its “race-proven” hulls.

Columbia built a third of the 153 Columbia 43s in Portsmouth, Virginia, and the rest in Costa Mesa, California. Most Columbia 43s are the Mk I version with the cast-iron deep fin keel and a design draft of 6 feet 11 inches. The Mk II version is a keel-centerboarder with a board-up draft of 4 feet 11 inches and a maximum draft of 10 feet 3 inches. The Mk II also carries about 1,000 pounds more ballast.

Columbia made the 43 from 1969 to 1974, and in the last two years produced a Mk III version. This had a redesigned lead-ballasted keel to reduce the wetted surface area, a skeg-hung rudder, a mast taller by 6 feet, and a 1-foot- shorter boom. The top of the bow was extended 6 inches, and this, with the rig changes, created a higher-aspect-ratio sail plan with the large foretriangle favored by the International Offshore Rule (IOR), the rating rule that replaced the Cruising Club of America (CCA) rule in the early 1970s.

Construction

A 1971 article in Boating magazine disclosed the layup schedule for the hull: 10- to 20-mil gelcoat, two layers of 3-ounce mat, one 24-ounce woven roving, one 3-ounce mat, one 20-ounce roving, one 1.5-ounce mat, 3⁄8-inch balsa core, a 2-ounce mat, and a 24-ounce roving. All the 43s had balsa-cored decks and balsa coring in the hull from near the keel to a little above the waterline. Adios has the expensive option taken by some original buyers of a fully cored hull, which improves its structural stiffness and provides some insulation.

Most of the interior features — the galley cabinets, dinette, and furniture — are part of a molded fiberglass pan dropped in before the deck was put on. Unfortunately, the pan was not well bonded to the hull. This is usually done with a putty applied wherever the pan contacts the hull, but it seems not to have been done well with many Columbias, and some owners have reported that the pan seems to “float” inside the hull. The woodwork, which was fitted after the pan was installed, looks good in most boats, but would not be judged high-quality. Some owners glassed over the inside of the hull-to- deck joint to stop leaks.

Accommodations

The 43’s versatile accommodations plan puts an efficient galley to port. It has double sinks near the boat’s centerline and two top-loading iceboxes. Craig stores dry and canned food in the larger icebox. The other icebox, outboard of the sinks, is refrigerated, and big enough that Craig’s mother could keep a turkey frozen so she could make a celebratory dinner at the halfway point during the Pacific Cup race. The galley is convenient to the cockpit, as is a U-shaped dinette to starboard that can accommodate six adults or more. Headroom in the galley and dinette is 6 feet 7 inches.

One step down, forward of the small gun-turret house and under the flush deck, the saloon has 6 feet 2 inches of headroom. The facing settees convert into four excellent sea berths. Forward of the saloon is a spacious head to starboard, and to port, a stand-up chart table with plenty of room for charts and electronics. The forward owner’s cabin has 6 feet 4 inches of headroom, a large V-berth, and two hanging lockers, one to port and one to starboard. The overall arrangement feels roomy and open.

The standard boat carried 48 gallons of fuel and 50 gallons of water in tanks under the facing settees in the saloon. Many owners ordered boats with an optional 70-gallon water tank under the V-berth.

Deck

The large flush deck is a boon both when sailing and at anchor. It eliminates that dangerous step up onto a coachroof and makes working at the mast feel safer. A dinghy can be stored in the 9 feet of space between the mast and the mainsheet traveler, so the foredeck can be kept clear while under way. For those who like a larger dinghy and don’t mind working around it, the foredeck will easily accommodate a 12-footer.

One of the boat’s most outstanding features is

its 10-foot-long cockpit. It’s comfortable, dry, and secure, and big enough to make grinding the winches easy, but not too big for snuggling into for a night watch. At anchor, the cockpit can accommodate at least eight people.

Rig

The Columbia 43 was rigged as a masthead sloop, but the boats came with hounds three-quarters of the way up the keel-stepped mast and a deck fitting to allow for setting a staysail with a wire luff. Racing skippers used this feature to set a deck-sweeping reaching staysail under a spinnaker. It’s also handy for setting a storm staysail. Bridge clearance for the Mk I and Mk II is 58 feet, and 64 feet for the Mk III.

As might be expected of a professional rigger, Craig made many modifications to Adios’ rig. One of the most noticeable is the roller furler fitted forward of the headstay, for which he added a cantilevered extension at the masthead and a 2-foot bowsprit at the bow. While cruising, Craig sets a self- tacking 90 percent jib from the inside furler and a 130 percent genoa from the outside one. For racing, he replaces the jib with the 130 and puts the asymmetric spinnaker on a top-down furler on the outside. The track for the self-tacking jib is simply a wire running between two pad-eyes on the deck in front of the mast. The sheet attaches to a large block, which he built out of an old masthead sheave, that runs along the wire.

Craig replaced two halyard winches with much-maligned wire-reel winches. He prefers wire over rope-to-wire halyards because of the cheaper cost and longer life of the wire, and he doesn’t have two big coils of line blocking his forward view. “A wire-reel winch is safe as long as you never release the brake with a winch handle in it,” he says. He also likes the old-style wire-reel winch that has a step cast into the horizontal top, a handy feature when furling the main, the foot of which is about 7 feet off the deck.

The single-spreader rig is robust, but Craig reinforced the deck attachments for the four lower shrouds because he sails the boat hard, sometimes in extreme conditions. He also replaced the mid-boom mainsail-sheet track with a heavy-duty Harken track.

Sailing

Adios sails well on any point of sail, and Craig particularly likes her performance in heavy weather. “These boats will break out and surf when conditions get extreme,” he says. “It’s safer and more comfortable than heavier traditional boats that dig a hole” as the wind increases. About the only condition she doesn’t do well in is light air and sloppy seas, he says.

On the Columbia 43, as on many boats built in the 1960s and early 1970s, the waterline length increases as the boat heels. So, even when motoring, Craig tries to induce moderate heel by setting the mainsail. He also tries to pack as many people as possible on the lee rail during light-air races, when heeling the boat with rail meat helps the sails set better.

What to watch out for

Columbia 43s have end-grain balsa-cored decks, so check for soft spots. Columbia used plywood as the core at the mast partners, shrouds, mooring cleats, and in other high-stress areas. Although the 43s had balsa core in part or all of the hull, problems do not usually arise because, unlike in the deck, there are few penetrations where moisture can intrude.

Although the standard engine was gas, most original owners spent the extra $2,050 (in 1971) for the Perkins 4-107 diesel option. These are famously reliable engines, so most boats still have them, although they usually have been rebuilt at least once.

Two times, Adios bent her rudder stock offshore: once when she broached while flying a spinnaker during an offshore race, and again when she hit a submerged log. “These are big boats with big rudders and the 3-inch rudder stock seems undersized to me,” Craig says, so he increased the size of the rudder stock himself with a 4-inch stainless steel tube and Harken rudder bearings.

Conclusion

Although considered a light-displacement racing machine in 1969, the Columbia 43 feels downright conservative nearly 50 years on. Its flush deck and relatively high freeboard are pure Tripp — shocking when compared to other designs of the day, but now unremarkable. It’s a boat that engenders a lot of love from owners, some of whom keep their boats too long and let the maintenance slip. But these are tough boats, and most can be brought back to Bristol condition with sweat and treasure. The good news is the effort is worth it: The Columbia 43 is a classic boat from a legendary designer that sails extremely well and has a comfortable interior.

Asking prices for the Columbia 43s vary widely depending on condition and location, but are usually between $25,000 and $60,000.

Brandon Ford, a former reporter, editor, and public information officer, and his wife, Virginia, recently returned from a two-year cruise to California, Mexico, and seven of the eight main Hawaiian Islands. Before their cruise they spent three years refitting their 1971 Columbia 43, Oceanus. Lifelong sailors, they continue to live aboard Oceanus and cruise the Salish Sea from their home base in Olympia, Washington.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com