“I really don’t know why it is that all of us are so committed to the sea, except I think it’s because in addition to the fact that the sea changes, and the light changes, and ships change, it’s because we all came from the sea. And it is an interesting biological fact that all of us have in our veins the exact same percentage of salt in our blood that exists in the ocean, and, therefore, we have salt in our blood, in our sweat, in our tears. We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea, whether it is to sail or to watch it, we are going back from whence we came.”

“I really don’t know why it is that all of us are so committed to the sea, except I think it’s because in addition to the fact that the sea changes, and the light changes, and ships change, it’s because we all came from the sea. And it is an interesting biological fact that all of us have in our veins the exact same percentage of salt in our blood that exists in the ocean, and, therefore, we have salt in our blood, in our sweat, in our tears. We are tied to the ocean. And when we go back to the sea, whether it is to sail or to watch it, we are going back from whence we came.”

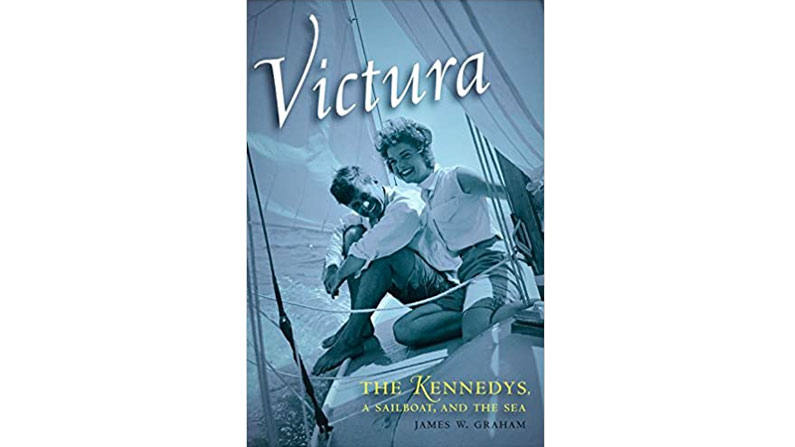

With these words at a dinner for the America’s Cup crews in September 1962, President John F. Kennedy spoke, I believe, for all sailors. It is well known that he and his brothers were sailors, but the impact of this sport on the lives of the Kennedys has not really been explored before this fine book by James W. Graham. For readers who have read full-length biographies of Jack or of his brothers Bobby and Ted, much of the broad story of the Kennedy family will be familiar. But here the role that sailing played in their lives steps forward, front and center.

This is a wise book as well as a great read. As Graham observes early on, “Sailors learn more from mistakes and close calls than from successes.” The Kennedy brothers plainly benefited from this truth, and that process began early in their lives. The brothers were fortunate to live in Hyannis Port on Cape Cod, and Jack and his older brother, Joe Jr., bought the family’s first sailboat, Rose Elisabeth, in 1927. Their youthful days were filled with sailing, first mastering the 16-foot Wianno Junior. In 1932, the family bought a 25-foot Wianno Senior (built then and still by the Crosby Yacht Yard in Osterville, Massachusetts), which they named Victura (“about to conquer” in Latin) and which they raced regularly in one-design class regattas. The next boat to master was a Star, and Joe and Jack each acquired Stars during the 1930s. Bobby also sailed Stars in the 1950s, but the Wianno Senior remained their favorite sailboat.

Graham spends three chapters tracing Kennedys through World War II, the 1950s, and JFK’s presidency. Here sailing takes a back seat to the broader story of the Kennedys, but the sport’s importance to the family is never lost. Jack particularly embraced sailing and the sea into his psyche, and as with many of us who sail, he was drawn strongly to images of sailing and the sea in literature and art. They became for him, and also similarly for his younger brother Ted, expressions of himself. Jack brought sailing and seafaring imagery in to his political speeches and, like Franklin Delano Roosevelt (who once served as Secretary of the Navy), Jack brought a seafaring décor to the oval office.

For the Kennedys, sailing was the family sport (despite the focus of media on their family football scrimmages), which regardless of gender all could participate in equally. Eunice, Jack’s younger sister, was a very good sailor, and Ethel, Bobby’s wife, was an excellent sailor and particularly turned to sailing following Bobby’s death. Jack’s nephew, Patrick, perhaps summed it up best that the sea, both arbitrary and constant, “is evolving, and yet it is also predictive, the tides come in and out. What a great metaphor for life.”

Victura is a lovely book. You’ll learn a bit about the history of sailing as well as a lot about one of America’s first families. This is a book for sailors and for admirers of the Kennedys.

Victura: The Kennedys, a Sailboat, and the Sea by James W. Graham (Foreedge, Imprint of the University Press of New England, 2014, 265 pages, 28 illustrations)