The catenary effect justifies carrying heavy chain rode. Right?

Issue 138: May/June 2021

Every sailor knows that in polite company, it is best not to discuss politics, religion, or anchors. But rode is fair game. After all, you will be hard pressed to find a sailor who doesn’t advocate attaching a length of chain to the anchor. Right? Are we all in agreement?

But why?

I think most folks will explain that chain adds weight to the rode, and that this weight near the anchor serves to keep the pull on the shank low. As Beth Leonard wrote in The Voyager’s Handbook, “The weight of the chain keeps the pull on the anchor parallel to the bottom, making it more difficult for the forces of wind and tide to trip the anchor.” From this, the progression is logical: the more weight, the better.

What she’s referring to is the catenary effect, the sag that results when gravity exerts its force on a length of chain supported only at its ends. The heavier the chain, the greater the catenary effect. So should you carry the heaviest chain you, your boat, and your windlass can reasonably manage? Should you use a kellet to add weight and induce further catenary effect? Are the benefits of the catenary effect worthwhile?

After more than 30 years and 100,000 miles of cruising, New Zealander Peter Smith says no. Several years ago, Smith (who co-designed the Rocna anchor with his son, Craig) published a compelling argument that the catenary effect disappears when most needed and should therefore be ignored as a consideration when selecting anchor rode.

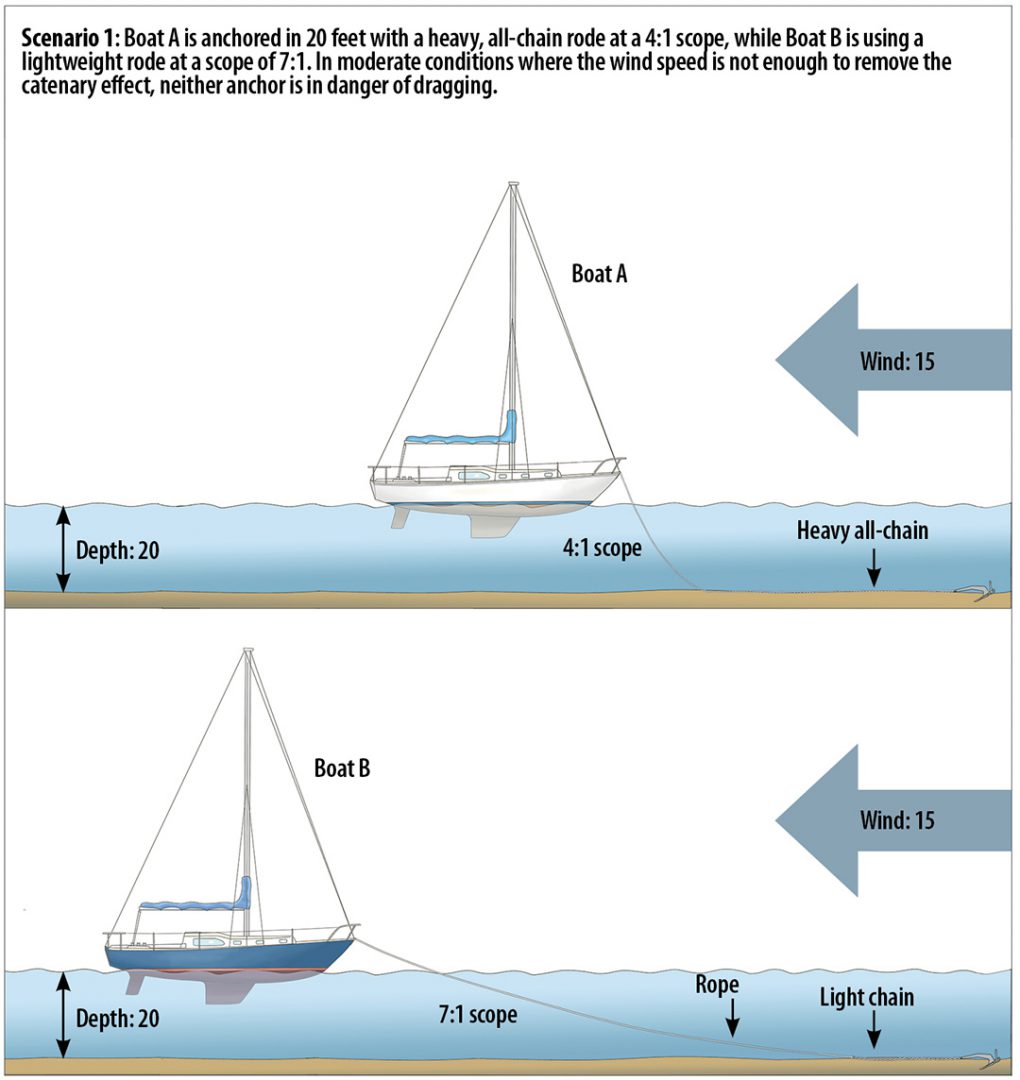

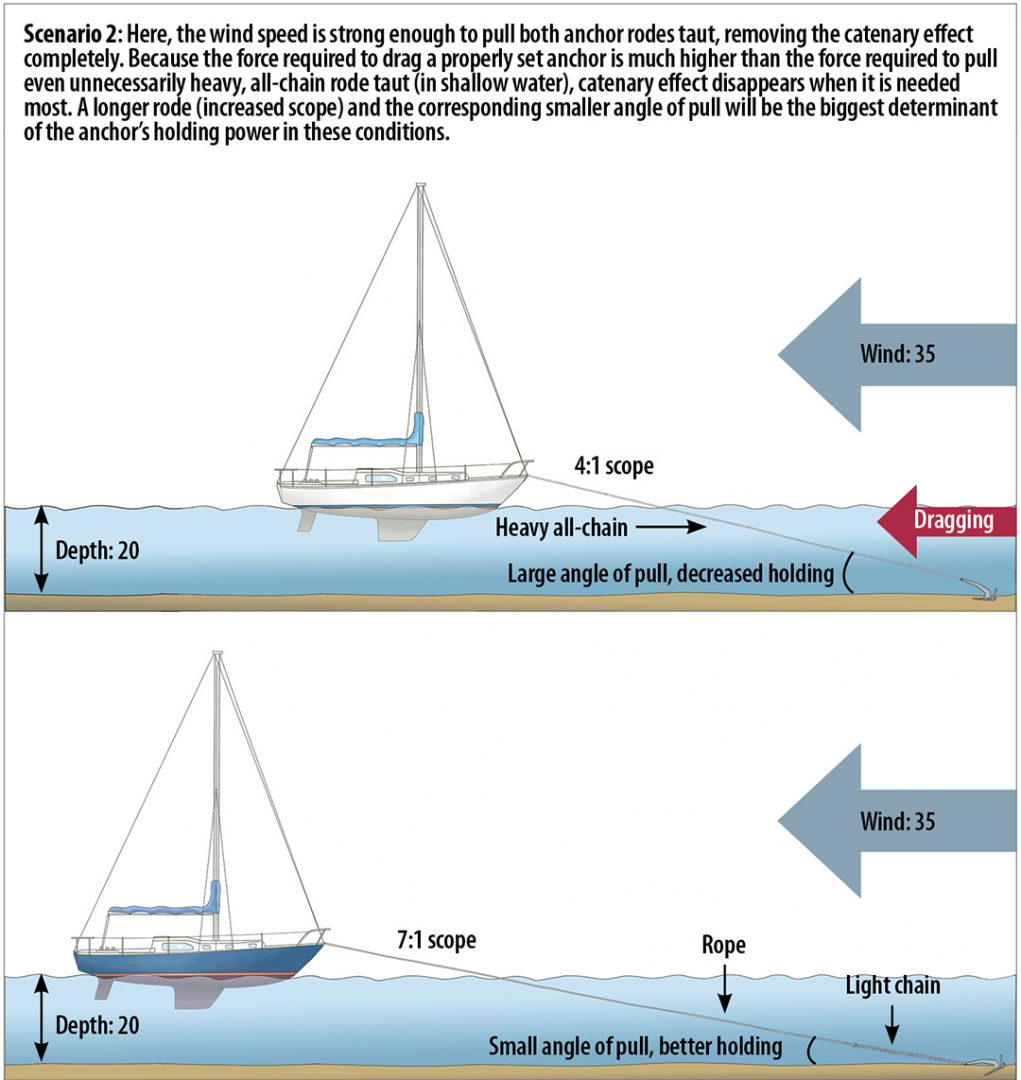

He doesn’t dispute the value of keeping the pull on an anchor shank as close to parallel with the seabed as possible—that’s how anchors are designed. But he argues that the catenary effect is not the best means to achieve this, only scope is. Citing data and mathematical models from Frenchman Alain Fraysse and Rocna Anchors of Canada, Smith says that in moderate conditions (wind speed of about 20 knots) in which the pull on the rode is not great enough to eliminate catenary (not enough force to pull the rode taut), a set anchor is not at risk of dragging.

And when conditions (wind speed of about 50 knots) exacerbate forces to the point where the rode is pulled taut and catenary is nearly gone, the angle of pull on the set anchor is primarily determined by scope; the weight of the rode is no longer a factor in the anchor’s ability to remain set.

“While catenary disappears, geometry cannot be argued with; for a constant depth, a longer rode means a lower maximum possible angle of pull on the anchor,” writes Smith. According to his argument, the catenary effect is both effective and superfluous up to the point it disappears.

Two adherents to this approach are lifelong cruisers and authors Steve and Linda Dashew. At the bow of the couple’s 83-foot, 50-ton Wind Horse is 3/8-inch chain attached to a 250-pound anchor. That’s the same weight/diameter chain we used aboard our 40-foot, 12-ton Fuji 40—and our anchor was just over one-quarter the size! (Of course, the Dashews use G7 chain, which has a much higher working load limit than our G3 chain—see sidebar).

Acknowledging that heavy chain rode is useless for increasing the holding power of a set anchor when the catenary effect is nearly eliminated, I asked Peter and Craig Smith about the role of the catenary effect in setting an anchor. Wouldn’t eliminating weight close to the shank make it harder to set an anchor in the first place?

They responded, citing anchor tests: “A modern anchor of adequate size will quickly offer resistance force as it begins to set. In testing, we routinely see the test line chain leader being mostly straightened before the anchor is even half set. The amount of force required to fully set an anchor is well over the forces catenary contributes.”

Some may point out the beneficial shock absorbing characteristic the catenary effect offers—especially when induced with a heavy all-chain rode. But the same argument applies: if the catenary effect that produces this benefit disappears with the onset of heavier conditions, a proper snubber should be rigged anyway, negating the value of the catenary effect.

Even discounting any benefits of the catenary effect, others will claim that heavy chain lying on the seabed produces friction that can serve to limit anchor re-sets in conditions where moderate winds are expected to shift. This may be a benefit of a rode made up of only heavy chain, but absent other reasons for otherwise unnecessary weight, this use case seems too limited to justify the approach.

So, are there any conditions for which it makes sense to carry heavier rode to induce a catenary effect? What about the Pacific Northwest, where anchorages often offer challenges that include deep water, fast-changing weather, and strong tidal currents?

It turns out that deep water is a special case.

The models Peter Smith uses in his technical article are based on depths (from the seabed to the roller) of about 25 feet. He readily concedes that in the case of an all-chain rode—and only in the case of an all-chain rode—the role of the catenary effect in deeper anchorages is greater (and the role in shallower depths is lesser).

This is because while all of the other forces remain constant, as the depth increases, the weight of the vertical column of chain increases and can be significantly greater when anchored in 85 feet of water, for example. To understand this, imagine you and your friend each holding the ends of a length of chain. If that length of chain is only 6 feet, it will be easy for you both to pull it straight. If that length of chain is 85 feet…you get the idea.

Accordingly, sailors with enough all-chain rode to deploy adequate scope in 100 feet of water may never see the wind speeds necessary to reduce the catenary effect to the point where it doesn’t play a role. In this case, heavier chain than needed—in terms of working load—may serve you well. Perhaps that is what John Rousmaniere meant when he wrote in 1983 about anchoring, in the first edition of The Annapolis Book of Seamanship, “While it won’t stretch, a chain rode is so heavy that it will take a hurricane to straighten it out.”

And of course, sailors who have long anchored successfully on ground tackle that is bought and paid for (including the gypsy), may not have much incentive to make an expensive, wholesale change. In fact, Peter Smith outfitted his Kiwi Roa back in the 1990s with both a windlass and a 300-foot length of heavy chain at each end (bow and stern)—and still used that setup decades later. Despite being a proponent for a contrary approach, cost kept him from changing.

Just as no two cruising boats are alike and no two anchorages are alike, no two ground tackle approaches are the same. Most cruisers swear by the anchor and approach that has worked for them and that allows them to sleep at night. But for those unsettled on a ground tackle solution or approaching the problem anew, it may make sense to reconsider the anchor rode, to rethink using heavy chain for the sake of inducing the catenary effect. And if you decide you can shed some pounds in the form of lighter or less chain, you may reduce pitching motion and improve sailing performance and fuel economy. Anchors aweigh!

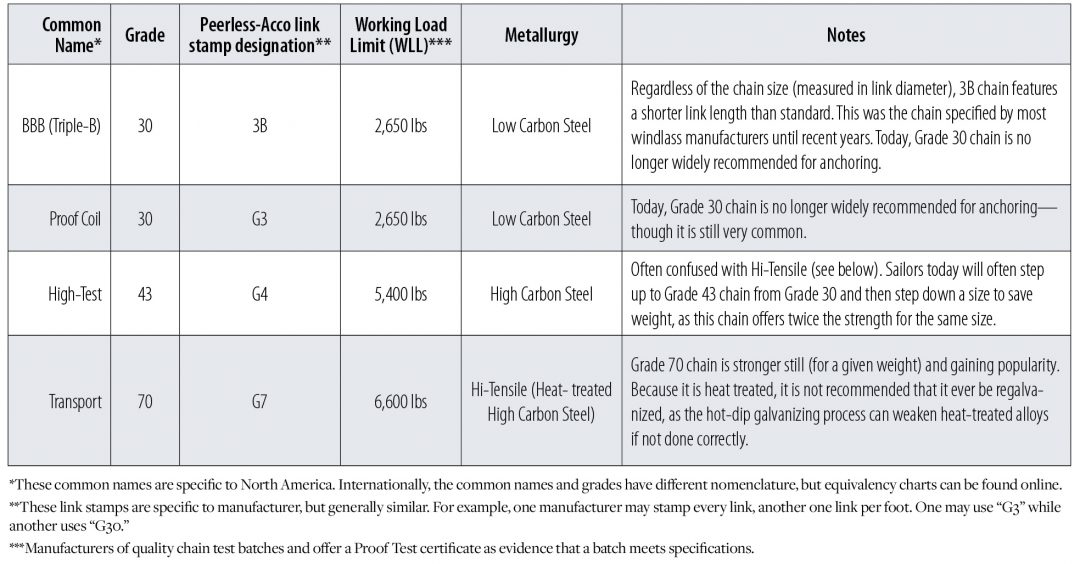

Chain, Chain, Chain

Years ago, when I first started investigating the windlass gypsy problems I had aboard our 1978 Fuji 40, I didn’t even know what it meant that my chain was stamped “G3”—and none of my dockmates at the time knew more than I did. I’ve since learned about chain, including what the G3 stamp means…and more. The following specs compare 10mm (3/8-inch) chain.

Michael Robertson is the editor of Good Old Boat.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com