Leave the weight in the lake and tow a lighter boat

Issue 127: July/Aug 2019

Water can be used in various ways to increase a boat’s stability. One method is as old as yachting itself. Æmilius Jarvis recounts that, when he was racing as a youngster in the 1870s, the crew would fill the yacht’s dinghy with water and haul it up on the yacht’s leeward deck prior to a tack. After the tack, the weight of the dinghy and water was then perched well out on the weather deck, adding a substantial amount of stability when sailing upwind. At that time in the history of yachting, such a maneuver was not illegal. More recently, around-the-world racers have employed water-ballast tanks located on each side of the boat at the point of maximum beam to place a substantial weight of water well out on the weather side. However, after an accidental tack or jibe, that water ends up on the new leeward side, where it detracts from stability and increases heel angle. That is why the amount of water ballast in these applications is often restricted. These are old and easily understood uses of water ballast to achieve higher stability.

The way water has been used as ballast more recently is perhaps not as easy to understand because, unlike in the above examples, the water is housed as low in the bilge as possible, on centerline, and below the waterline. When fixed in the bilge, water makes an ideal ballast material for trailerable boats, as it can be easily taken on after the boat is launched and allowed to drain out during haulout, usually on a trailer at a launch ramp. That eliminates the need to haul several hundred pounds of deadweight behind the tow vehicle. Indeed, the use of water ballast in these applications is, to my knowledge, exclusively restricted to boats that are launched and retrieved by trailer on launch ramps.

The first boat to popularize water as ballast in this way was the ubiquitous MacGregor 26, which was introduced with a daggerboard in 1986 and a swing keel (centerboard) in 1990. Hunter and Catalina were soon to follow. When I joined Hunter Marine in February of 1992, the project on the drawing board was the water- ballasted Hunter 23.5, with a lot of the design work already completed by my then-new associate Lynn Myers. It should surprise no one that a MacGregor 26 was sitting in the Hunter test pond behind the plant. The successful Hunter 23.5 was launched in 1992, and it was quickly joined by the water-ballasted Hunter 19 in 1993 and the Hunter 26 in 1994. The water-ballasted Catalina 250 came out in 1995.

How water ballast works

Some people have trouble grasping the concept of water used as ballast in this way: How can a material that has neutral buoyancy in water act as ballast? Doesn’t ballast have to be heavier than water (lead, iron, or concrete) to increase stability? The answer is no. This harks back to the old children’s riddle of which weighs more, a ton of lead or a ton of feathers. Obviously, they both weigh a ton, and both, if used as ballast, will increase the boat’s displacement and thus stability.

Just as the ton of feathers will certainly occupy more volume than a ton of lead, the requisite weight of water will occupy more volume than an equivalent weight of lead or iron, but it is the weight that is important. As long as the water is restrained, its weight accounts for 35 to 50 percent of the total displacement or weight of the boat, and if located as low as possible in the boat, it will act as ballast. The result is that the boat’s total center of gravity has been lowered and its stability increased.

On these water-ballasted trailerable boats, the water is always carried in a tank located between the cabin sole and the hull, and acts like the inside ballast used in the broad-beamed centerboard sloops of the 19th century. This concept of ballast located low in the hull and not in the keel was used in the 1978 Canada’s Cup winner Evergreen, where the entire lead ballast was cast in the shape of the bottom of the hull and bolted to a flat on the hull designed to accept it.

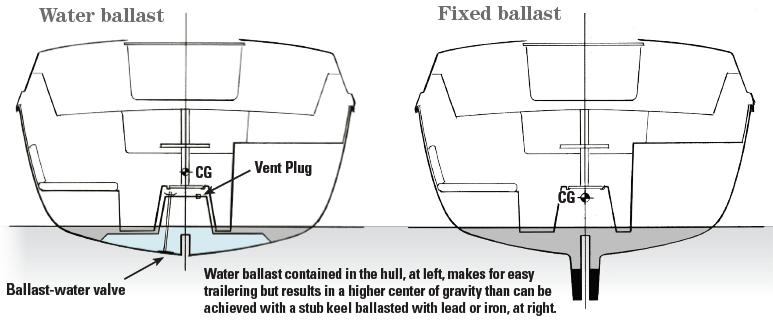

The principle behind the use of ballast, whether water or lead, is exactly the same: Stability is increased by increasing the boat’s displacement and lowering its center of gravity (CG). Keep in mind, though, that water ballast will occupy more than 10 times the volume of the same weight of lead, and this will affect the location of the CG. Due to its much smaller volume, the lead ballast would have a lower CG than the water, and this would lower the total CG of the boat more than the water ballast would. To partially compensate for the higher CG location, the weight of water ballast used is often greater than that of the lead ballast required to achieve the same stability.

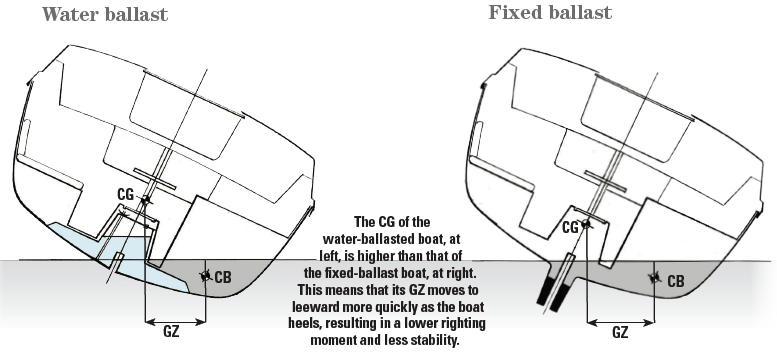

There is a reason to concentrate as much ballast as low in the keel as possible. A yacht’s heeled stability is generated by the shift of the center of buoyancy to leeward as the boat heels under a press of sail. The center of buoyancy (CB) is the center of the volume of the hull below the waterline.

The buoyancy, equal to the total displacement of the hull, acts as a force upward through the CB. The weight of the boat, which is equal to its displacement (Archimedes established that a body floating in water displaces its own weight of water), acts downward through the boat’s CG. The horizontal distance between these two forces is the righting arm, referred to by naval architects as the GZ. A “moment” is a force times a distance, so the “righting moment” is equal to GZ times the weight of the vessel.

When a boat is upright, the CB and the CG are in the same vertical line and the GZ is zero. As the boat heels, the CB and CG separate horizontally and GZ increases until the righting moment is equal and opposite to the heeling moment generated by the wind force on the sails and the hydrodynamic lift on the hull and keel. Therefore, for a given weight of boat, the righting arm, and thus the righting moment and stability, can be increased by maximizing the horizontal distance between these two forces of buoyancy and weight.

The righting arm can be lengthened by increasing the beam of the vessel so that more hull is immersed farther to leeward as the boat heels. The wider beam is said to contribute to form stability. The righting arm can also be increased by lowering the center of gravity of the vessel so that there is little movement to leeward of the CG as the boat heels.

Stability constraints

Water-ballasted trailerable boats, unfortunately, are caught in a bit of a bind with both paths to higher stability. With regard to form stability, increasing beam is limited by the maximum vehicle width allowed on the highways, which is almost universally 8 feet, and possibly 8 feet 6 inches in some jurisdictions. Any boat wider than that will require a wide-load permit for each state or province through which it travels. The MacGregor 26 mentioned above has a 7-foot 10-inch beam, the Hunter 23.5’s is 8 feet 3 inches, the Catalina’s is 8 feet 6 inches, and that of the Hunter 26 is a pushing- the-limits 9 feet. So, increasing form stability by increasing beam on boats in this size range is strictly limited. This is also the reason that, to maximize beam at the waterline, most water-ballasted trailerable boats are somewhat slab-sided.

Water-ballasted trailerable boats, unfortunately, are caught in a bit of a bind with both paths to higher stability. With regard to form stability, increasing beam is limited by the maximum vehicle width allowed on the highways, which is almost universally 8 feet, and possibly 8 feet 6 inches in some jurisdictions. Any boat wider than that will require a wide-load permit for each state or province through which it travels. The MacGregor 26 mentioned above has a 7-foot 10-inch beam, the Hunter 23.5’s is 8 feet 3 inches, the Catalina’s is 8 feet 6 inches, and that of the Hunter 26 is a pushing- the-limits 9 feet. So, increasing form stability by increasing beam on boats in this size range is strictly limited. This is also the reason that, to maximize beam at the waterline, most water-ballasted trailerable boats are somewhat slab-sided.

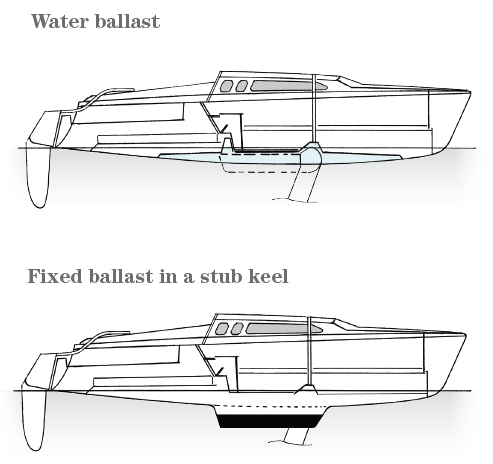

Increasing stability by lowering the ballast CG is limited because these boats are designed to be launched off trailers at boat ramps. A number of trailerable boats use lead ballast contained in a short stub keel that also houses the centerboard. This locates the CG of the ballast as low as it possibly can go, but the ballast is fixed, and adds about 40 percent of the weight of the boat to the load on the tow vehicle when compared to a water-ballasted boat.

However, by concentrating and lowering the ballast, the boat’s total CG is also lowered substantially. As seen in the accompanying illustrations (above) of both ballast configurations at 25 degrees of heel, the righting arm (GZ) of the water-ballasted boat is about 15 percent shorter than that of the shoal-draft boat with fixed lead ballast. This results in a direct 15 percent reduction in stability and sail-carrying ability. Obviously, if a deeper-draft fixed keel were used, the CGs of the ballast and the boat would be lowered even more, with a corresponding increase in GZ and stability.

Because of the lower stability of the water-ballasted boat, it’s advisable to be able to quickly dump wind from the mainsail when hit by a gust. For that reason, all the water-ballasted trailer- able boats, with the exception of the Catalina 250, have fractional rigs with larger mains and smaller jibs.

Water-ballast management

Water ballast used in place of the same weight of fixed lead ballast occupies 10 times as much volume. This greater volume consumes most of the space between the sole and the hull, and there needs to be some way to admit water into the ballast tank after the boat has been launched. This is achieved by removing a vent plug from the top of the tank and opening a valve in the hull bottom to let water flood the tank. The vent plug must be well above the waterline so that, when the tank is completely filled, water will cease to enter, despite the valve and vent still being open. For that reason it is often located in a molded step at the companionway. When the tank is full, and water has stopped flowing, the hull valve is closed, usually against a rubber pad, and the vent plug is reinstalled.

For the system to work properly, the tank must be completely full and the valve tightly closed. If the tank is only partially filled, not only is the amount of ballast reduced and the boat’s total CG higher, but a “free surface” is created, and when the boat heels, water will flow to the leeward side of the tank, shifting the ballast CG to leeward and further shortening the righting arm.

Ensuring that the tank is completely filled might require “burping” it by walking around the boat to heel it on both sides and trimming it bow-down so any air in the tank shifts aft to the vent plug. To encourage trapped air to flow to the area of the vent plug, the top of the ballast tank is usually sloped fore and aft.

Because the vent plug sometimes does not provide a completely airtight seal, especially if it’s not installed properly, it is important not to overload the boat to the extent that the vent plug might go beneath the boat’s flotation plane. This can happen if there are too many people in the cockpit and the boat is fully loaded for extensive cruising. If the boat is overloaded and the vent plug is not installed properly, water might weep into the boat, causing it to float even lower in the water, making the situation worse. (Just such an incident at a Hunter Rendezvous led to an associate of mine coming to the rescue of a family aboard a 23.5, which later led to a romance with the daughter and a very happy marriage.) It is also important that the vent plug be high enough on centerline that water in the ballast tank does not reach the level of the plug even at high angles of heel.

One other caution with water ballast, especially on freshwater lakes, is the obvious fact that in cold temperatures, water will freeze, and when it does, it expands 2 percent in all directions. If the water in the ballast tank is allowed to freeze it can do severe structural damage to the hull or ballast tank. It’s advisable, therefore, to always drain the tank completely after hauling the boat, and to avoid leaving the boat in the water in freezing conditions.

If transporting the boat between different lakes, it is certainly necessary to drain the tank so as not to transport invasive species. A useful precaution is to add a little bleach to the water as the tank is filling.

The use of water ballast has created an expanded market for trailerable pocket cruisers, because these lighter boats can be hauled great distances behind smaller vehicles and easily launched and retrieved from most public launch ramps. The concept works well, but it’s important to recognize the compromises in reduced stability as a result of a higher CG and the restriction on beam. These boats were designed primarily for inshore and lake use, and perform that function very well. Any departure from that should be considered carefully.

Rob Mazza is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. He began his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, working for Cuthbertson & Cassian. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new, and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com