Set fasteners to the right tightness with a wrench torque

Issue 127: July/Aug 2019

“Remember, Eddie, one hand on the socket end of the wrench and your other hand perpendicular to the end of the handle. Now, pull gently until . . .”

Snap went the handle! “I broke it!”

“No, Eddie, that’s the way it’s supposed to work. Pull until the wrench clicks and that’s it.”

I was 16 years old, in an ice-cold Pennsylvania garage pit under a car with Big George. We were replacing the main bearings on a ’51 Plymouth and I had just used a torque wrench for the first time. I was doing a real grown-up job with a real grown-up tool and I was being taught by the best. Big George looked like Jimmy Stewart and his delivery was that same Jimmy Stewart drawl.

“Now, let’s try the other side. Left hand on the socket. Nice steady pull. When you feel the click, stop.”

Click! I was hooked!

Torque is a twisting force that operates in a way to rotate or turn an object. Those of us who get up close and familiar with our good old boats use wrenches frequently to apply torque to a nut or bolt to loosen or tighten it. When tightening, we usually keep going until that “feeling” tells us it’s tight enough, but who hasn’t at one time or another applied so much torque that the bolt has broken or the head has twisted off?

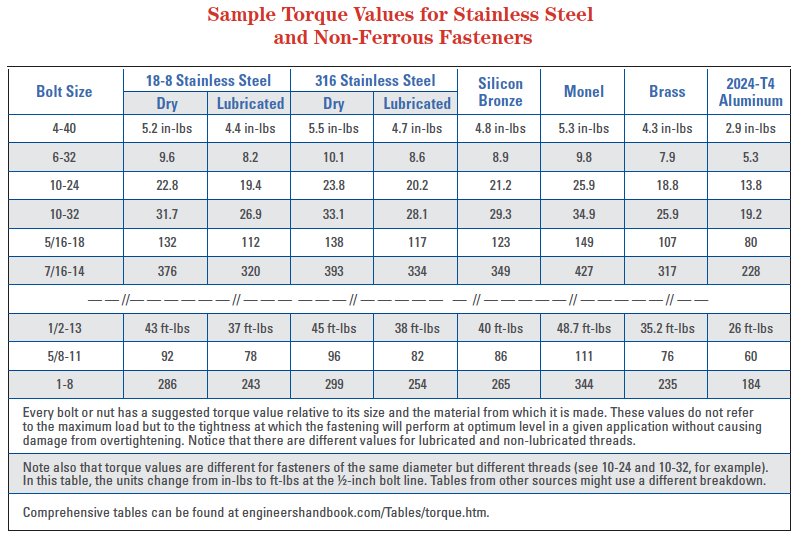

In many applications, getting the torque right is critical, and engineering organizations have calculated tables of specific torque values for every size of nut and bolt (see the table on page 25). Exceeding these values risks stretching or breaking a bolt, stripping threads, or damaging a part the bolt is being used to secure.

In a set of standard open-end or box wrenches, the length of each wrench is matched to the size of the fastener it is used for — short for smaller-diameter fasteners and longer for larger ones. The purpose is to limit the amount of torque that can be applied. If the wrench is used properly, there should be little danger of over-tightening unless you pull like Hercules. This is fine where the tightness of an assembly is not critical to its function, but when working on machinery, such as that Plymouth’s transmission or its engine’s cylinder head, torque matters. The car’s manufacturer will have developed a specific torque value for every bolt in the assembly. The mechanic must know what those values are (they are in the service manual) because over- or under-tightening can lead to serious problems.

Enter the torque wrench, a special kind of socket wrench with a built-in mechanism that can be adjusted to tighten a nut or bolt to a specific torque.

Purist engineers say that the only truly accurate way to measure tightness is by measuring bolt tension through “bolt stretch,” that the torque wrench is a poor proxy for measuring bolt tension, and that tightness derived from a torque wrench is prone to many inaccuracies. While this may be true in the strict engineering sense, such measurements are far beyond the resources of us mere mortals, especially at sea. Thus, the lowly torque wrench will have to do. Besides, manufacturers of engines and other complex machinery have done their homework and established torque values for every nut, bolt, and screw in their products. Every car, truck, boat, or aircraft engine assembly I have ever witnessed employed a torque wrench. Plus, if it’s good enough for NASA . . .

Measuring torque

In the US, the most common units used to express torque are the foot-pound (ft-lb), for larger fastenings, and the inch-pound (in-lb), for smaller fastenings that need lighter torquing.

A foot-pound of torque is defined as one pound of pull on a lever one foot long, the pull being perpendicular to the lever.

The metric units are the newton meter (N-m) for large fastenings and meter kilogram (M-kg) for small fastenings.

Applying 65 pounds of “pull” to a 1-foot-long wrench creates 65 foot-pounds of torque. The torque wrench is designed to measure this exactly. Torque wrenches are made in lengths to suit the torque values they are intended to measure — shorter for lower values and longer for higher values. Whatever the actual length of a particular torque wrench, it is constructed and calibrated to precisely achieve the desired torque.

Types of torque wrench

The beam wrench is simple and inexpensive. While not terribly accurate, it is better than nothing. The main drawback to this design is that reading the gauge at any angle other than from directly above can result in a serious error. Because the head does not ratchet, I found this wrench very difficult to use in the confines of our engine room aboard Entr’acte, where there was insufficient room to swing the wrench and read it correctly.

The click wrench is a vast improvement over the beam wrench. It is built with internal mechanisms that can be preset to the desired torque. To operate it, twist the handle until the indicator reads the desired torque, fit the wrench to the fastener, and pull gently. When the applied torque reaches the set value, the handle flexes with an obvious “click” that can be felt as well as heard. A lock at the bottom of the handle prevents the setting from changing while the wrench is being operated. This design is far more accurate than the beam wrench and not overly expensive. The click wrench is most desirable because its accuracy does not depend on the user being able to see anything. You can be in the most convoluted position putting all of your thought and energy into pulling that handle until you hear that rewarding “click.” The click wrench has a ratchet head that makes it easier to work with in a confined space.

Torque wrenches come in many sizes. Larger ones are calibrated in foot-pounds (newton meters) and smaller ones are calibrated in inch pounds (meter kilograms). They typically have the US scale printed on one side and the equivalent metric scale on the other.

The range of settings for a standard torque wrench can vary. The most common ranges are 10 to 150 foot- pounds, 20 to 200 foot-pounds, and 30 to 250 foot-pounds. For torque values above 220 foot-pounds, a larger wrench or a “torque multiplier” would be needed, but such high torque values are extremely rare.

Using a torque wrench

When embarking on a project that requires the use of a torque wrench, first determine, from the engine service manual or a table of torque specifications, the torque values needed for each fastener, and write them down. Then check them again.

Make certain that whatever you are torquing cannot move! Applying 60 foot-pounds of torque even to a heavy engine could move the engine unless it is properly secured, and that could lead to injury or damage to the boat.

Clean all friction surfaces thoroughly using either brake cleaner or acetone.

Lubricate all threads and friction surfaces with a quality oil. Engine oil works best. Avoid light oils such as 3-in-1 or WD-40.

Install each fastener in the proper sequence and turn them by hand until they are finger tight.

Set the torque wrench to one-third of the final desired torque (click wrenches). For a final torque of 88 foot-pounds, begin by applying 29 foot-pounds to each fastener in the prescribed sequence.

Using a torque wrench is always a two-handed operation. If you neglect to support the fulcrum with one hand you will at best be inaccurate but will also stand a very good chance of breaking a bolt or your hand.

Position your body and brace yourself so that you can make a nice smooth steady pull. (This can be a real challenge in a confined engine room.)

Make certain the ratchet is fully engaged.

Use precisely the right size socket for the fastener.

Never use a socket that is worn or has visible cracks — if the ratchet or socket slips or breaks it can damage the fastener or cause a hand injury.

Fit the socket onto the bolt or nut and place one hand on the socket end of the wrench to support the fulcrum. With your other hand, grasp the handle of the wrench perpendicular to the handle with your fingers facing into the direction of pull. Yes, this matters! Look directly at the needle (beam wrench), and with a gentle motion, pull steadily until the gauge reads 29 and stop. Do not jerk on the wrench and do not push it! With a click wrench, pull steadily until you hear and feel that unmistakable “click” and stop. Do this for each fastener according to the prescribed sequence.

Reset the wrench to 58 foot-pounds (two-thirds) and repeat the sequence.

Finally, reset the wrench to the final figure of 88. In confined spaces with limited swinging room, the ratchet head of the click wrench is a definite advantage, but be careful. When using a click wrench it is possible to overtighten a fastening. As soon as the wrench clicks, stop! That’s it!

Avoid long extensions and crowfoot accessories, as they flex and result in false readings.

Using a torque wrench is serious business. If visitors drop by, ask that they return when you are done. There is a real danger that any distraction from the task could cause you to misread the manual or make some other dumb mistake.

To loosen and remove bolts, use a breaker bar, not the torque wrench. Working in the reverse sequence to that used for installing them, release the tension in stages of approximately one-third at a time. This prevents undue stresses and damage to critical metal castings.

Maintenance

A torque wrench is a fine precision instrument and should be treated as such. Keep it in a sealed plastic box and stow the box where it cannot be splashed on or become immersed in water. Should the wrench get wet, rinse it with fresh water, dry it, and oil it well. Rust will destroy it. Inspect it periodically. After 25 years, our wrench looks and behaves as if new.

Never store a click wrench with the spring under tension, not even a little, but release the tension completely after use. A spring stored under tension will weaken and compromise the wrench’s accuracy, which could result in stretched, broken, or stripped bolts, stripped nuts, cracked engine castings, and prematurely blown gaskets.

Who needs a torque wrench?

A torque wrench is not needed for tightening every nut or bolt on board. In most cases a standard open-end or box wrench will do nicely. A torque wrench will more than earn its keep, though, should a cylinder-head or exhaust gasket blow in an area far from the nearest mechanic (see “Dead in the Water,” January 2015). Even if you carry the engine manual and spares for these two gaskets on board, and you should, without a torque wrench, your repair will be very short-lived and lead to serious engine damage. Perhaps you don’t have the confidence to perform the engine work yourself, but having a torque wrench on board would enable someone with the experience to assist you who, without the proper tool, would be powerless to help.

A torque wrench is not needed for tightening every nut or bolt on board. In most cases a standard open-end or box wrench will do nicely. A torque wrench will more than earn its keep, though, should a cylinder-head or exhaust gasket blow in an area far from the nearest mechanic (see “Dead in the Water,” January 2015). Even if you carry the engine manual and spares for these two gaskets on board, and you should, without a torque wrench, your repair will be very short-lived and lead to serious engine damage. Perhaps you don’t have the confidence to perform the engine work yourself, but having a torque wrench on board would enable someone with the experience to assist you who, without the proper tool, would be powerless to help.

Aside from complicated internal engine work, the torque wrench is valuable for many seemingly mundane tasks as well. Almost every part of an engine is designed to be installed and tightened to a specified torque. When installing such items as water pumps, fuel pumps, and thermostats, we usually tighten them by feel, but when is a bolt or nut tight enough that it won’t vibrate loose? When is it too tight? Reading the sections about these items in the engine manual will reveal that their torque values are surprisingly light. When you use a torque wrench, there is no doubt when you have the tension right.

Even the lowly hose clamp is assigned a suggested torque value; for a #8 clamp (½-inch hose) it’s 24 to 35 in-lbs and for the #20 clamp (1½-inch hose) it’s 45 to 60 in-lbs. These are quite low values, far lower than we are tempted to apply by feel, and explains why our attempts at clamping hoses fail, either by cutting the hose or by overstressing the clamp.

I also use the wrench in certain rigging applications, such as chainplate installations or whenever multiple fastenings are involved, to ensure that they are all uniformly tight.

Choosing a torque wrench

When buying a torque wrench, assess your personal needs and select what works for you. I find that a small wrench of 20 to 200 inch-pounds (16 foot-pounds) and a larger one of 10 to150 foot-pounds have covered the entire range of anything I have encountered on board. The only exception is the large trailer-hitch bolts (250 foot-pounds) for our 15,000-pound-capacity trailer.

A quality click wrench can be purchased for as little as $50 and upwards. Don’t look for a bargain. Whatever you might pay, remember, if it saves you a single dockside mechanic’s bill, it has paid for itself three times over. Yes, using it is an acquired skill, but with a bit of practice you take one giant step closer to being self-sufficient when dealing with your good old boat.

Read, Check, and Check Again

I learned the hard way how important it is to read the engine manual carefully more than once and to write down the torque values and tightening sequence before working on the cylinder head.

Way back in the “before time,” I was retorquing Entr’acte’s cylinder head. I had clearly read the number 13 in the manual, and even though a little voice told me that this was a ridiculously light cylinder-head torque, I set the bolts at 13 foot-pounds. The engine started and ran well, and we proceeded to cross the North Atlantic without incident. After we’d arrived in the Azores, we had to change our mooring. The engine started, then immediately shut down with a sudden belch as water ran freely from the air intake, a classic example of a blown cylinder-head gasket.

The head-bolt torque in the manual was indeed 13 — newton meters — and next to it in parentheses was its equivalent: 86.8 foot-pounds. The manual had clearly given figures for both metric and US units, and had I read it more closely, I would have used the 86.8-foot-pounds number in parentheses. This is a very common mistake.

We were perhaps lucky that I made my mistake on the cylinder head, and luckier that the damage was not greater — an improperly tightened cylinder-head gasket will leak and allow cooling water to mix with the lubricating oil, or warp or crack the cylinder head causing an engine failure, perhaps at an inopportune moment. Had I made the same mistake on the exhaust manifold, the result might have been exhaust gases inside the boat, which could have been deadly, as those gases include carbon monoxide.

Ed Zacko is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. Ed, the drummer, and Ellen, the violinist, met while playing in the orchestra of a Broadway musical. They built their Nor’Sea 27, Entr’acte, from a bare hull, and since 1980 have made four transatlantic and one transpacific crossing. After spending a couple of summers in southern Spain, Ellen and Ed shipped themselves and Entr’acte to Phoenix, Arizona, where they refitted her. They have since towed her to the Southwest US and have also been cruising on her in the Bahamas. Follow them on enezacko.com.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com