What’s old is the latest thing

Improve performance! Save weight! Save money! Cut down on steering failure and cockpit clutter! Sound like an advertisement? It should be, but it isn’t. Since the tiller has little commercial value, no one pushes the clear advantages of this tough little item. Yet slowly and surely, the innovative side of our sport is turning the pages of an old book to discover a new idea. Just as long bowsprits (rig extensions) are now de rigueur on many modern race boats, tillers are making a comeback. A careful look at the advantages makes the opening statements completely justified for cruising boats and race boats up to and even longer than 40 feet (12.2 m). If you then look at some of the subtleties of designing and building the deceptively simple tiller, you might find it the most logical choice for your next boat. If you already have a tiller, some simple ideas and accessories could make it more user-friendly than ever.

Advantages of a wheel

Originally, all ships were steered with a tiller. If they were hard to steer, blocks and tackles were added to assist the helmsman. Then along came the wheel to provide easier, faster steering than a tiller with its awkward tackles. Though yachts were far smaller, and thus easier to steer than big ships, many suffered from weather helm. This tendency for the boat to want to head up into the wind if firm pressure is not held on the tiller can have some advantages, but if it is excessive, it exhausts the helmsman. Curing weather helm can mean doing anything from raking the mast forward to moving the whole mast forward, from recutting the sails to adding a bowsprit. But the simplest and most common solution used by many builders was to add extra leverage in the form of a wheel. It wasn’t a cure; it only disguised the problem, but it definitely reduced the tendency to stretch the arms of the helmsman.

Once wheels began appearing on yachts less than 40 feet (12 m) in length, other advantages became apparent. Now you could invite your favorite uncle out for a daysail, and he could take over steering immediately. No more having to explain, “Just pull the tiller this way to make the boat go that way!” You could simply say, “Steer it like your car.”

People feel good about themselves when they are standing behind a large, leather-clad wheel. This appearance can be just as important as the benefit of having a neat position for a compass and cockpit table mount on the wheel pedestal. Yet the most important reason for having a wheel remains firmly in the realm of big boat racing. Only with a wheel can the helmsman keep clear of the flying elbows of the winch crew.

There are other advantages to having a wheel. Yet, when you compare these to the advantages of a tiller, you may begin to wonder if fashion has been the main influence in making wheels so prevalent among boats less than 40 feet in length.

Advantages of a tiller

Although tillers have always had firm adherents among determinedly practical cruising sailors — ranging from Eric Hiscock to Hal Roth, and from Don Street to Bernard Moitessier — it is among the high-speed racing fraternity on their new sportboats — like the J class, Melges 24 and 30, and the Mumm 30 — that tillers have begun a swift reemergence. The reason is simple. The full-on racer on a sporty boat wants to keep weight off the ends of the boat. No quadrant, no cables, no 200-pound helmsman at the back end of the cockpit equals less hobby-horsing (pitching).

The tiller is more sensitive to boat responses than a wheel. Not only does it give faster, more positive rudder adjustments, it telegraphs information back to the helmsman to let him know if the boat is balanced properly. This is important, as even a 5- or 6-degree rudder angle can cause drag that can slow the boat.

Cruisers might not feel the extra bit of speed is important, but most will agree that a tiller makes installing some form of self-steering far easier, and self- steering is the most important aspect of enjoyable offshore voyaging. Whether wind-vane or electrically operated, it is easy to disconnect self-steering quickly from a tiller. Simply lift the control link free of the tiller lock pin. If for some reason your wind-vane self-steering or autopilot dies completely, the tiller provides a hidden option unavailable to those with wheel steering. With about $50 worth of simple gear, you can rig up a sheet-to-tiller steering system.

Sheet-to-tiller steering system

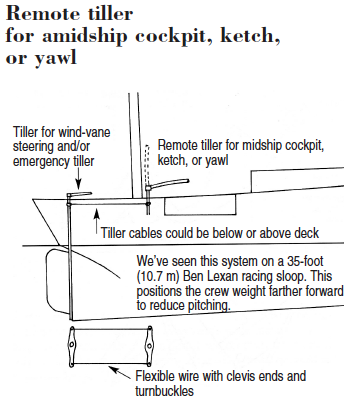

Another plus for tillers in combination with an autopilot or self- steering gear is that the best control point for the connecting lines or push rod are usually about two feet forward of the rudderhead. This makes the controls far less intrusive and much less of a hurdle for the crew than the port and starboard control lines of wind-vane steering led to a wheel. Combine this with the absence of the wheel itself, and fore-and-aft traffic in the cockpit becomes far easier.

Sculling with a tiller is a tactic so useful among smallboat racers that there are special rules governing it. Even on cruising boats up to 44 feet (13.4 m), you can use the side-to-side swinging of the rudder to move your boat toward a new breeze, or the few yards forward you need to come up to a mooring or dock for an almost-perfect landing. This tiller sculling is like a secret weapon for racing sailors and those who cruise without engines — onshore or offshore. In very light breezes, it is easy to lose steerage. With a tiller, you can use what we call “the half scull” to swing the bow of the boat so it lies at a close-hauled position to what breeze there may be. This new angle to the wind will get the boat moving faster than it would on a downwind course, because as the boat gains forward momentum, its speed is added to the actual wind speed to give a stronger apparent wind. Once you get moving, you can ease off onto a beam reach and keep sailing, despite the light wind.

To us, one of the most worrisome aspects of wheel steering — and a very important reason to choose a tiller — is the growing number of serious, wheel-inflicted injuries caused by breaking waves washing crew against wheels. Dana Dinius of 44-foot (13.4 m) Destiny had his femur shattered when a wave smashed him against the wheel during a storm north of New Zealand. Michelle Perot, on board Maiden, broke several ribs and bent the wheel so badly it jammed the steering for several minutes until the crew used tools to rebend it clear of the pedestal. Chay Blyth built special guardrails to keep crew on his latest Round the Southern Capes (west-about) Race from hitting the wheel when waves swept along the deck and into the cockpit. He told us, “Last race, wheels caused the only serious injuries, including a shattered wrist when a crew member was swept against the turning wheel.”

And finally, even if you have a wheel, you still need an emergency tiller. No matter how carefully your system is installed, the mechanical complexities leave it more susceptible to steering failure. The most common problem (other than seasickness) listed for the 1979 Fastnet Race storm and the 1994 Queen’s Birthday storm (near New Zealand) was wheel-steering breakdown. So some of the following ideas could help even if you only use a simple tiller as a backup for your wheel.

Building a stout, reliable tiller

Your tiller should be strong enough so that when a 200- pound (90 kg) crewmember falls heavily down onto it, it won’t break. How strong is that? Larry says: “I like to test a tiller by putting it in a big vise then jumping on it and heaving my whole weight on its forward end (I weigh about 180 pounds). If I can’t break it, then it should withstand the test of sailing.”

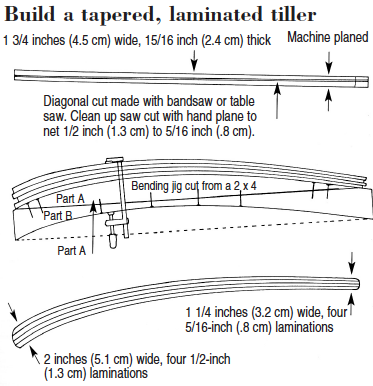

A tapered tiller will have a tendency to bend a little under severe loads and thus is less likely to shatter than a stiff, parallel-sided one. The curve you see on most tillers is for appearance’s sake or to assist in clearing obstacles or knees in the cockpit; it is not a necessity. So to make tiller-building easier, you can choose a simple tapered, straight shape. Build it out of a rot-resistant wood — such as pitch pine, black locust, or teak — to ensure longevity.

A one-piece tiller is preferable, as the ones we have seen fail are most often curved, laminated ones. If you decide to laminate a tiller, use heatproof, waterproof adhesives such as resorcinol, Aerodux 185, Aerodux 500, or Cascophen. These adhesives are reliable and can be used to laminate a teak tiller that will be left unvarnished in the tropics. The strongest, most cleverly designed laminated tiller we have seen was made from tapered pieces of wood. This meant that the outside laminations did not taper off to leave unattractive feather ends.

Tiller-to-rudder connections

The most reliable, easiest to build tiller-to-rudderhead connection is the mortise-and-tenon type such as shown in the photo above. This works best with an outboard rudder. For inboard rudders, a metal tillerhead-to-shaft fitting is necessary.

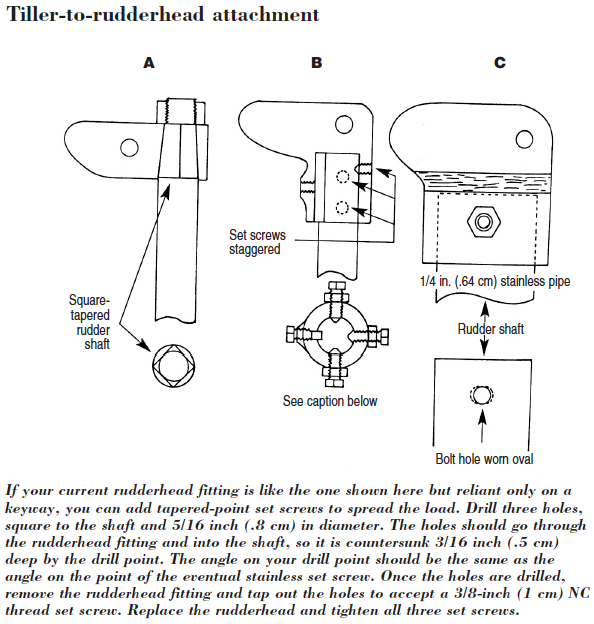

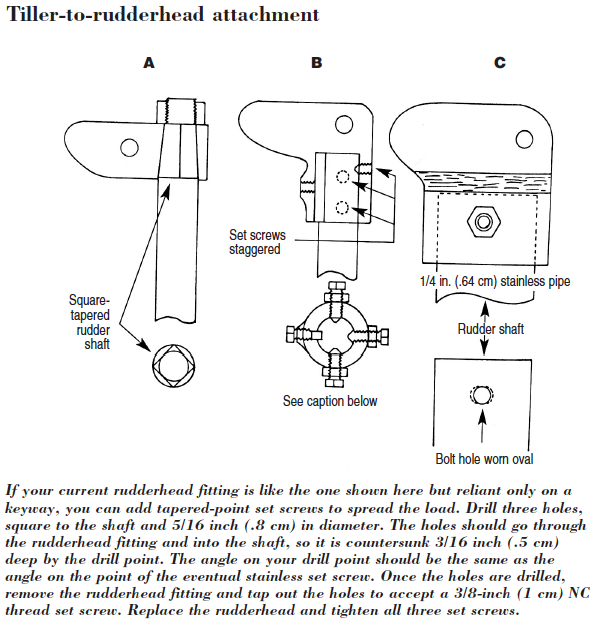

The illustration below shows three different tiller-to-shaft connections with which we have sailed. A is the most reliable, but unfortunately it is least common, because the machining time needed to get a close fit on the square taper makes it the most costly. The square-taper connection works similarly to your propeller-to-shaft connection; it is essentially a squeeze play between the two parts. But it is even better than the prop connection, as the large surface area of the square acts like a huge keyway to resist wear and loosening. B, on the other hand, is prone to loosening. The constant, often forceful, corrections from wind-vane steering gear can distort the keyway during a long tradewind passage. One way to help alleviate this keyway wear is to add tapered-point set screws, as shown at B in the illustration below. These set screws can be tightened, even at sea.

Version C below shows the worst kind of rudderhead-to-tiller connection with which we have sailed. It is extremely susceptible to wear. During the delivery of one new 35-footer (10.7 m), we had 1/4-inch (.64 cm) of wear in 1,100 miles on a 1/4-inch- thick, 4-inch (10.2 cm)-diameter stainless-pipe rudder shaft. A larger- diameter bolt can help in this situation, but the best fix would be to weld a tight-fitting compression plug, then use multiple set screws to locate the tiller more firmly, as shown in B.

Making it work for you

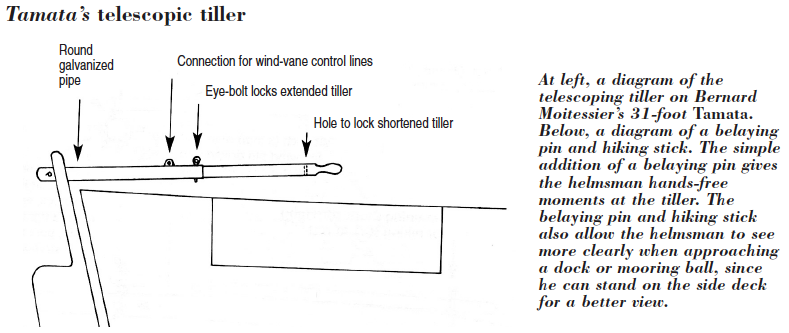

It is particularly helpful to be able to remove the tiller completely when it is not in use, as in the photo on Page 13. When we are in port, this clears the cockpit for socializing or sleeping. It also makes the boat theft-proof, as you can remove the tiller and lock it away below. At sea, it is nice to be able to shorten the tiller to make the cockpit feel more commodious. Bernard Moitessier had a telescopic tiller on his last boat, 31-foot (9.5 m) Tamata. To achieve a similar reduction in length, you could also make a folding tiller.

But with wind-vane self-steering or autopilot during a passage, it pays to have a good, long tiller. As the photo at right shows, this long tiller is accessible from the companionway, so you can luff up in a gust of wind or steer clear of floating logs or weed. We find this long tiller especially handy during wet weather, as the person on deck can go forward to drop a sail and the person down below does not have to don foulweather gear to assist in steering. He/she can just reach out and push the helm without releasing the self- steering. The boat luffs up for a bit, the sail comes down, and the wind-vane takes over again.

Simple tiller accessories

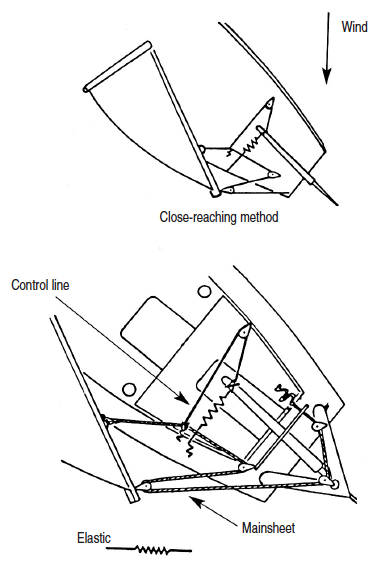

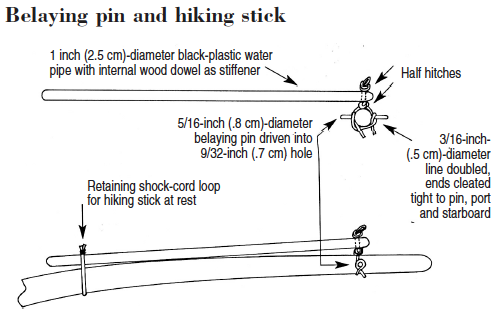

By adding a thwartships belaying pin to the inboard end of your tiller, you can use adjustable port and starboard shock cords to help your boat self-steer more comfortably in heavy winds (see illustration on Page 18). The shock cords can be adjusted to dampen the wind vane’s correcting movements and, in effect, act as a shock absorber to cut down on overcorrection. The shock cords can also be adjusted to put in a bit of lee helm or weather helm so the vane helps you track more accurately. This is especially helpful on a broad reach in fresh winds and long, rolling seas.

Even without a wind vane, the tiller belaying pin would be useful for securing sheet-to-tiller steering. Although it is usually offshore cruising sailors who need various options for self-steering, this clever system can be of interest to a wide range of sailors — whether a lone daysailor hoping to enjoy lunch with both hands free or a raceboat delivery crew heading home short-handed. We have included a couple of the basic diagrams from John Letcher’s book, Self-Steering for Sailing Craft, to help you begin experimenting. After using his methods on several boats we have to agree when he says, “Sheet-to- tiller gear can do your steering, simply and reliably, on all points of sailing.”

The final use for the tiller belaying pin is, to us, one of the most important. It can be the basis of a cheap, easy-to-make hiking stick. A hiking stick on an 8-ton cruising boat? Yes, we find it really useful when we are approaching a dock or mooring ball, as it lets the helmsman stand on either the port or the starboard side deck to get a perfect view of the objective. Since you are now out of the cockpit, it is easy to hand someone the aft mooring line, or to step off and secure the line to the dock. If you are approaching someone’s boat, they are reassured by seeing you standing on the side deck holding a mooring line for them to use to stop your boat as it glides alongside under power or sail. The simple system shown at right includes a shock-cord loop to keep the hiking stick out of the way when you don’t need it. Complete removal of the hiking stick is easy for offshore sailing.

For the prudent sailor, a potential backup tiller is probably on board right now. Before you set off cruising, adjust one of your dinghy oars so it will fit your rudderhead fitting.

The new wave of sport boats is encouraging designers to recycle the tiller. As they do, they are working to make new boat designs more balanced, so that tiller steering is a breeze. The good news for owners of all types of boats — ketches, yawls, sloops, or cutters with inboard or outboard rudders — can be read in the balance sheet. You could use the money you save to get out cruising sooner.

Pros and cons: Comparing the wheel with the tiller

Wheel

- Makes steering less tiring by controlling weather helm

- Increases mechanical advantage

- Feels familiar — steers like a car

- People feel good standing behind a wheel

- Pedestal makes a good center-of-cockpit grabrail, compass mount, and table mount

- Does not sweep across cockpit so is less worrisome to visitors

- Makes installation of a below-decks electronic autopilot easier (definitely better for salt-sensitive electronic gear)

- Keeps crew clear of helmsman for racing

- Clears cockpit for thwartship crew traffic

- Makes installation of a second steering station easier, i.e., for inside and outside stations

Tiller

- Ultimately reliable

- Ultimately inspectable

- Low maintenance (few moving parts)

- Simple installation

- Low weight

- Low purchase price

- Clears cockpit for fore-and-aft traffic

- Lets helmsman reach winches easily for sheet adjustments (Important for short-handed sailing)

- Easy to remove to clear cockpit area

- Easier to rig vane or autopilot steering

- Faster steering, i.e., you can make radical course changes more quickly

- Lets you sense small changes in sail trim or balance of rig

- Serves as an obvious rudder-angle indicator for the whole crew (also for photographers)

- Enables you to use rudder to scull the boat in light winds

- Lets you put tiller between your legs to steer temporarily and free up your hands to handle jibs or toss a mooring line

- Lets you steer the boat from various positions inside and outside the cockpit – especially with a hiking stick

- Less liable to injure crew

- Provides a base for tiller-to-sheet self-steering

- Keeps weight of crew and gear out of end of the boat

- No need for separate emergency-tiller arrangement

- Lets helmsman get out on side deck with hiking stick (two wheels needed to do this on racing boats)

Fitting a wheel to a modern 30-to 33-footer

(This information is based on an average of prices provided by West Marine Products using Edson International components, for boats such as the Pearson 30, Columbia 32.)

Materials only — including pedestal, stainless-steel destroyer- type wheel, chain and rope assembly, and all gear to connect this system to the rudderhead, below cockpit floor level average $1,232.00

Normal accessories

Pedestal guard: 109.00

Steering brake: 92.95

Labor at $35 per hour, average 16 hours:560.00

Estimated cost: $1,993.95

Tiller steering

Materials – tiller: 54.92

Rudderhead fitting: 119.00

Estimated cost: $173.92

(Tiller and rudderhead fitting would still be required with wheel for emergency steering.)

Excerpted from Cost-Conscious Cruiser, Lin and Larry’s newest book. This and other Pardey books are available from Paradise Cay Publications, 800-736-4509.