A few — of many — rules to race by

Issue 126: May/June 2019

Robb Lovell introduced readers to the fun of racing (“Testing the Waters in PHRF Part 1,” January 2019) and shared tips on how to sail fast (“Testing the Waters in PHRF Part 2,” March 2019). In this issue, he provides a primer on the basic rules a sailor needs to know to compete safely and with confidence on the racecourse.

Any competitive activity needs a common set of rules to make it fair and fun. For sailors, whether racing in dinghies, good old boats, or ocean greyhounds, those rules are laid out in The Racing Rules of Sailing for 2017-2020. In book form, the rules fill nearly 200 pages. If that sounds daunting, veteran sailor and rules analyst Dave Perry’s book, Understanding the Racing Rules of Sailing Through 2020, runs to more than 300 pages. The rules are promulgated by World Sailing, the international authority for the sport, and govern sailboat racing worldwide.

No sailor new to racing need be daunted, however. The rules are based on the Navigation Rules, with which every sailor should be familiar. Specifically, they build on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972 (72 COLREGS) Rule 12 (Sailing Vessels) and Rule 13 (Overtaking) to clarify competitors’ responsibilities in the many boat-on- boat situations that arise when racing.

Most sailboat racing is conducted without referees or umpires, and racers are expected to police themselves and race within the rules, which build upon three guiding principles:

Competitors shall assist other vessels or persons in danger.

Competitors shall carry the appropriate safety gear.

Competitors shall follow and race by the rules and are expected to show good sportsmanship.

To feel confident on the racecourse, a novice racing sailor needs to understand a few basic racing rules. Understanding the finer points will come with experience and through discussions with fellow sailors.

Rule building blocks

When a fleet of boats is tacking and jibing around a racecourse, the scene on the water can appear chaotic, and sometimes intimidating to a newcomer to racing. Close encounters between boats are common, and the principal goal of the third guiding principle of the Racing Rules is to ensure that those encounters are not too close. The rules that assure this, by establishing which vessel in an encounter can maintain its course (stand on) and which must keep clear of the other (give way), are the most important ones to know. Note that 72 COLREGS do not use the term “right of way,” because no vessel has the right to sail into another.

-

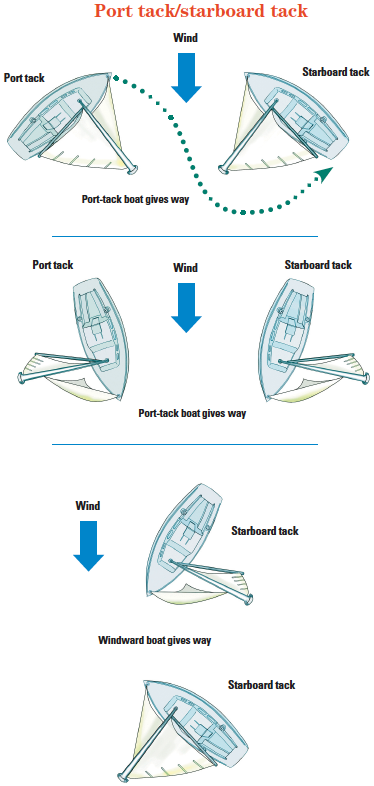

Boats on opposite tacks

A boat on port tack shall keep clear of a boat on starboard tack (see diagram “Port tack/starboard tack”).

This is the most fundamental rule in sailboat racing and is based on 72 COLREGS Rule 12.

A boat is on starboard tack when the wind is coming over its star- board side and its boom is to port.

A boat is on port tack when the wind is coming over its port side and its boom is to starboard.

The position of the boom is important. If a boat is sailing downwind by the lee, the wind might be coming over its starboard quarter, but if the boom is to starboard, the boat is deemed to be on port tack.

When sailing on port tack, whether sailing upwind or off the wind, keep an active watch for boats on starboard tack — and make sure a crewmember is watching the helmsman’s blind spot behind the headsail. At some point, you will be crossing tracks with starboard-tack boats, and it’s your obligation to keep clear of them. If you can safely cross ahead of a starboard-tack boat, do so, but if in any doubt, bear away and dip behind its stern.

When sailing on starboard tack, don’t be complacent and assume that port-tack boats are as diligent as you are. Watch for port-tack boats that might enter your space, and inform them of your presence by hailing “Starboard!”

-

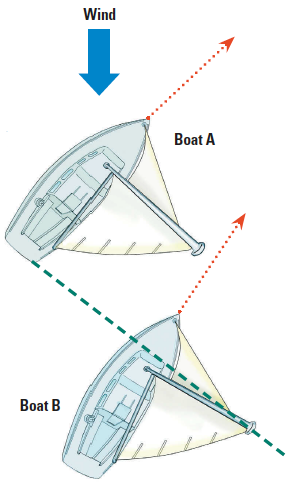

Boats on the same tack

Where two boats on the same tack are overlapped, the windward boat must keep clear of the leeward boat. An overlap is established when the bow of the boat behind is forward of a line extending from the aftmost point of the boat in front perpendicular to its centerline.

The windward boat is the boat that is closer to where the wind is coming from. So if your boom is pointed toward the side the boat overlapping you is on, you are the windward vessel and must keep clear of the leeward boat. If the leeward boat can out-point your boat upwind, it has the right to take you up to weather.

-

On the same tack, not overlapped

When one boat is overtaking another, the overtaking boat must keep clear of the boat being over- taken (72 COLREGS Rule 13). Once the overtaking boat has established an overlap, the windward/leeward and overlap rules come into effect.

-

On the same tack, meeting

When boats on the same tack are in a meeting or crossing situation, the windward boat must keep clear of the boat to leeward (see diagram “Port tack/starboard tack”).

- Changing tacks

When tacking, a boat must keep clear of all other vessels.

You must not tack into another vessel or into its path. A tack begins when a boat’s bow passes through the wind and is complete when the boat is on its proper course on the new tack.

-

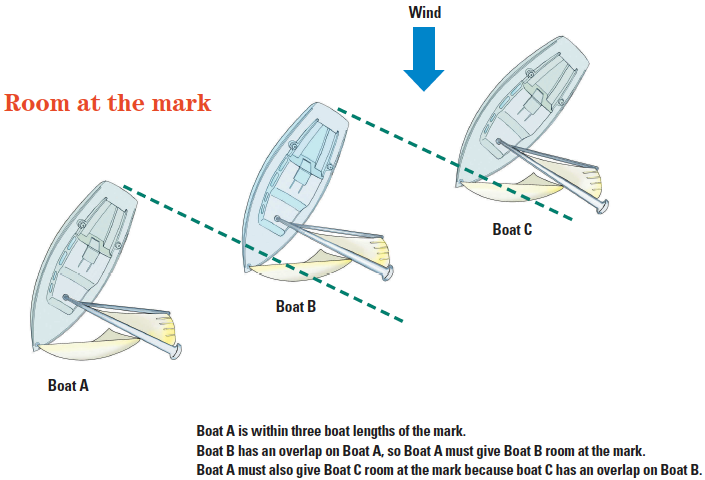

The mark zone

Mark roundings can bring a lot of boats into close quarters, and the racing rules are designed to bring order to the potential chaos. As soon as a boat is within three boat lengths of the mark, it is in the mark zone.

A boat in the mark zone must give “room at the mark” to any boat on its mark side that has established an overlap. (This rule also applies to obstructions on the course.)

This rule can create a chain effect, because the boat with the overlap must give mark room to any boat that has an overlap on it.

When approaching a mark, keep a sharp eye out for boats on courses that could bring them between you and the mark. If you are the following boat with an established overlap, hail the overlapped boat with “Room at the mark!”

- Changing course

If your boat is the stand-on vessel and you wish to change course, you must give any give-way vessel in close proximity the opportunity to avoid a collision. Before changing course, hail the other boats to inform them of your intentions and give them time to take action. Simply put, a stand-on vessel cannot make a course change that causes a collision.

-

Avoid contact

Collisions are to be avoided. If a give-way vessel does not appear to be taking action to keep clear of a stand-on vessel, the stand-on vessel must take action (72 COLREGS Rule 2). Just because you are on starboard tack, you do not have the right to ram a port-tack boat that’s in your path. Collisions can cause injuries, damage to boats, and bad blood between sailors, none of which contribute to making racing fun.

Protests, penalties, and redress

In sailboat racing at the club level, where most of us with good old boats race, there are no referees. We racers are expected to govern ourselves and one another. Central to this concept is the protest. If another boat on the course fouls yours, you can protest. You can also protest a boat that breaks a rule by, for example, neglecting to round a mark. There are several requirements for a protest to be valid:

You must be directly involved in or have directly witnessed the offense against which you are protesting.

You must hail the boat being protested and inform the crew that you are protesting. This must usually be done immediately after the incident that prompted the protest, but if the boat is out of hailing range you must inform it of your protest as soon as possible. The hail can simply be “Protest!” Although not required, you may also inform the crew of the rule they breached.

You must, at the earliest opportunity after the incident, display a 6- by 6-inch red protest flag and fly it (usually off the backstay) for the remainder of the race. The protest-flag requirement is waived for boats under 6 meters in length, but failing to fly a protest flag on a larger vessel can lead to the protest being thrown out, as the flag is considered an important part of informing the offending vessel of your intent to protest.

You must inform the race committee as soon as possible of your protest.

For most rule offenses, the penalty incurred by the offending vessel is to complete two 360-degree turns once it’s clear of other boats. (Usually, the offending boat will make its penalty turns as soon as the crew acknowledges the hail from the protesting boat.) But if an offending boat isn’t aware it’s being protested, or disagrees with the protest, it won’t make the penalty turns and the matter will be taken up by a protest committee post race. Statements will be taken from both skippers, a protest hearing will be convened, witnesses will be heard, facts gathered, and a ruling issued. If the protest is deemed valid, the protest committee will assess a penalty appropriate to the infraction.

If a protest on the course involves a serious incident, such as a collision that results in damage to a vessel or injury to a sailor, or if the offense gave the offending vessel a substantial advantage in the race, the protesting boat may request redress or a penalty more severe than penalty turns.

Racing your boat in close proximity to others is thrilling, but skippers need clear rules to follow so the boats don’t get too close, and they need to know and understand those rules. It’s a cool — athough often frustrating — aspect of the sport of sailboat racing at the club level that the racers are self- governed. Because there are few, if any, officials or referees on the course, that the sailors know and respect the rules is important for them and for the sport. It is truly the integrity of the skippers that makes the sport honest and fun.

Tips for Sailors New to the Racing Rules

Racing at the club level is supposed to be fun, so keep it that way by taking the time to study and know the basic rules.

Obtain a copy of the The Racing Rules of Sailing. Although lengthy, the rules are well-written and reader-friendly.

Use the off-season to expand your knowledge by reading books about the racing rules.

Before a race, read the Notice of Race and the Sailing Instructions published by the club or organizing body, as they will provide you with valuable information specific to the race or series you will be competing in.

During a race, don’t get closer to other boats than your skills and comfort level allow. If in doubt, back off. Remember that your competitors are fellow sailors, club members, and friends. Action on

the racecourse can get heated, but do your best to keep it civil, and mend fences as soon as possible when there is an issue or protest.

After a race, think about encounters you had during the race and try to apply the rules. If you have questions about the rules, don’t be afraid to ask a knowledgeable sailor for help. At my club, after almost every race, somebody commandeers a chalkboard on which to illustrate an encounter someone had on the course. The ensuing discussion informs us of the rules that apply to the encounter and helps us all understand them better.

These sessions have taught me that two sailors can look at an encounter from very different perspectives, apply different rules based on those perspectives, and come to widely different conclusions. But it is through these discussions that we all come to a better understanding of the rules and become better able to govern ourselves as sailboat racers.

Protests do arise at our club, but they are rare, and most issues are worked out with penalty turns or treated as learning opportunities.

Resources

The Racing Rules of Sailing with the US Sailing prescriptions is available as a book and, to members of US Sailing, as a free download and an app: ussailing.org/competition/rules-officiating/racing-rules

The navigation rules for international waters are laid out in the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972 (72 COLREGS). In the US, the Inland Navigation Rules are published in 33 CFR 83. Both sets of rules are printed on facing pages in The Navigation Rules and Regulations Handbook, published by the US Coast Guard and available online and through marine retailers. navcen.uscg.gov

Canadian sailors can find links to the Racing Rules of Sailing and the Sail Canada prescriptions at: sailing.ca/rules-prescriptions-s15703

The Canadian Collision Regulations can be found at: laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/C.R.C.,_c._1416

Robb Lovell grew up sailing on Lake Huron aboard his family’s Endeavor 40, where he caught the sailing bug. That was about 20 boats ago. Rob enjoys buying and restoring boats, and is an avid racer and cruiser based out of LaSalle Mariner’s Yacht Club (LMYC) in Ontario. He currently races on a Cal 9.2 named Jade but owns three other sailboats and a tugboat . . . yes, he has a problem!

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com