A Head-Turning Shoal-Draft Cruiser.

Issue 135: Nov/Dec 2020

Lake Mendota, just north of Madison, Wisconsin, is my home water; it’s also where the late, great Buddy Melges sailed. Wide and deep, it’s a great place for sailing an able, mid-sized boat, and Mike and Kathy Stich have found their Seaward 26RK, Blue Dancer, to be ideal.

Mike’s career has included EMS and ice diving, while Kathy is retired from banking. Mike came to sailing via his father’s Snark, later a Victoria 18, and then the Seaward.

Mike’s career has included EMS and ice diving, while Kathy is retired from banking. Mike came to sailing via his father’s Snark, later a Victoria 18, and then the Seaward.

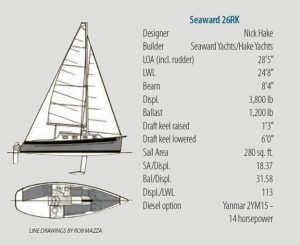

With a retractable rudder and lifting keel, the Seaward 26RK can squeeze into the skinniest waters with its 15-inch minimum draft yet perform well in a seaway. Handsome, spacious, and well- built, these boats are much loved by their owners.

History

Designer and builder Nick Hake founded Seaward Yachts of Stuart, Florida, in 1973 and began building this model in 2005. It remains in limited production with about 250 produced.

In 2010, Hake sold Seaward Yachts to a private investor who changed the name to Hake Yachts, and Hake remained on board to manage things. This same investor purchased Island Packet Yachts (IPY) and combined the companies in IPY’s Largo facilities. Later, the owner sold Seaward and Island Packet to a California Island Packet dealer. Today, this company, under the Island Packet banner, has the molds for all Seaward boats except the Seaward 46RK, which remain with Hake and a business partner who are currently negotiating for future production.

Hake continues to repair, upgrade, and broker the 2,300 Seaward Yachts out in the world. He remains the primary source for upgrading the 26RK with new keel and rudder systems, though IPY does this work as well. Hake told me that owners of early Seaward 26RKs do not hesitate to spend the $10,000 or more that it takes to upgrade the early keel and rudder systems to the latest versions, which include a more robust rudder cassette and lighter rudder blade. Blue Dancer has these upgrades, made by IPY.

Design

The 26RK is characterized by jaunty sheer, mild tumblehome, boxy trunk house, nearly plumb bow, and a practical bowsprit. It is the sort of boat you admire as you row away in your dinghy.

The road-legal beam of 8 feet 4 inches and fairly firm turn of the bilge aid in keeping the boat stiff—even with the keel and its bulb retracted (bulb weight is 800 pounds on early boats and 1,000 pounds on later builds for a total ballast of 1,200 pounds). With the keel down, draft is 6 feet, providing plenty of lift for windward sailing. There is sufficient form stability and internal lead in the hull to keep the boat upright even if the bulb is lost, which has happened on earlier boats.

The fiberglass and carbon- fiber rudder lifts clear in a cassette hung on the transom; this has been updated on more recent models to make the boat stern-beachable, a change that can be retrofitted to earlier boats. The transom is open but can be a bit cluttered by the outboard on a bracket, unless the boat has the optional inboard Yanmar diesel. Displacing 3,800 pounds, the 26RK is no Tinkerbelle, but a boat with enough weight to beat through a steep chop while providing a comfortable, dry ride.

With keel and rudder fully retracted, the 26RK can dry out on a low tide and be beached if the bottom is soft. And while not necessarily a boat one would want to trailer each time it’s used, it can be towed by appropriate vehicles and launched from a good ramp.

Construction

The hulls are mostly solid fiber- glass but with Coremat coring to provide stiffness in flat areas. The laminate schedule incorporates a blister-resistant vinylester gelcoat, a skin coat of chopped strand mat, and triaxial fabrics.

Interior features, such as berth flats and galley, are part of a pan bonded to the hull at strategic locations. While this saves man-hours over a plywood interior, it does inhibit future customizations and makes for a moister, noisier interior. Beds for an inboard engine are part of the pan to accommodate repowering an outboard- powered model with a small diesel.

The deck is cored with Divinycell foam and secured to the hull with a proprietary putty and stainless steel machine screws every 6 inches. Deck hardware such as cleats are fastened to tapped 1/8-inch aluminum plates embedded in the laminate.

Owner Ken Lee says, “The early models (2005 to 2009 or so) had a design flaw in the way the lead bulb was attached to the keel blade. There was about 200 pounds of lead in the blade and an 800-pound bulb attached to the blade with fiberglass. A number of boats lost their bulbs for various reasons. We knocked ours off hitting a reef on Lake Havasu going maybe 2 knots. We eventually had the keel replaced with the new design, which has all 1,000 pounds of lead in a manatee tail-shaped bulb bolted to the blade. The boat was noticeably stiffer after that.

“The other design issue with early boats is a rudder that couldn’t be fully retracted. It extended about 12-18 inches below the hull. This stopped you from being able to beach the stern of the boat. Worse yet, you had to be careful hauling the boat, so you didn’t scrape the rudder when towing through steep dips in the pavement. By 2010, I believe the keel design had been changed to bolt-on and the rudder redesigned so it lifted all the way up in the cassette.”

On Deck

The tall topsides, combined with the tall cabin trunk, give standing headroom of around 5 feet 10 inches below. The sidedecks have well-designed molded non-skid with a bulwark below the lifelines that provides great foot-stopping power.

The jib sheet car is right at the joint between the sidedeck and cabin trunk—out of the way, yet handy to the cockpit, which provides for tight sheeting.

The cockpit is quite roomy with long seats that have deep storage below. The lifelines terminate at two stainless steel pulpits that incorporate catbird seats—a favorite spot for crew to hang out. The starboard seat swings up for fuel tank access.

The open transom quickly disperses any water that comes aboard, and handles on either side make it easier to climb in from the water. A removable arched seat spans the opening for the helmsperson. The Edson wheel is a bit in the way to get around, and it does not really work well for a swing-up table addition (the seats are too low).

The traveler occupies the tiny bridge deck, bringing the mainsheet readily to the helm on tiller-steered boats, but a bit out of a reach for someone at a wheel. Some owners put the mainsheet on a pennant to raise the cam cleat to an easier-to-use height, but Mike reports this tends to bang about.

Forward are two teak or metal handholds on each side of the cabintop. Four opening portlights on each side plus a forward hatch provide plenty of light and fresh air. All are top quality materials, with swing-up inner glass lenses and two hold-down dogs. In fact, all over the Seaward 26RK you will find almost anything metal to be chromed for protection; it is one of the first things that catches your eye, no more so than on the 2-foot bowsprit.

There is plenty of deck space, and placing the anchor at the end of the bowsprit keeps the foredeck uncluttered and the anchor well clear of the hull. Some owners complain that the chain locker and hawsepipe are small and troublesome, particularly if a powered windlass is installed.

Rig

The mast is supported by a 7/8-fractional rig with single spreaders. Shrouds and inner stays are mounted inside the sidedeck walkway, keeping passage forward clear. Inside the cabin, chromed rods anchor these stays, transferring the load down low to the hull structure. Hake claims the backstay is redundant and that the mast will stand without it and is too stiff to bend.

Below Deck

The Seaward 26RK is fairly comfy for a 26-footer. While the centerboard trunk occupies space visually and physically, one soon learns to live with it. The dining table has an innovative mechanism to swing up out of the way around the trunk.

The 48-inch-long galley is to port with an icebox, stove, and sink. To starboard is an enclosed head compartment with shower and toilet; some may have a sink. To port is a short settee while to starboard is a much longer settee that could be a berth. The V-berth is the main sleeping choice, but it is open to all else except for curtains—unless an owner asked for the bulkhead and door option—and is a bit short for taller crew.

Forward of the V-berth is access to the anchor rode locker. Bulk storage is some-what lacking, with the portside quarter berth becoming the catch-all. Boats with a diesel inboard lose much of the quarter berth and lazarette space under the cockpit.

In all, the cabin is easy to clean with smooth-finished fiberglass surfaces in an off-white color, yet with enough wood, cloth, and other materials to make it feel elegant. Thoughtful handholds make sailing safer as well. As a final unique feature, everything can be removed from the cabin and the inside cleaned with a hose!

Underway

The Seaward 26RK makes way best with about 10 degrees of heel but feels entirely solid at 20 degrees. Most owners reduce sail at 15-17 knots of wind. Designed for single-handed sailing with a sport- boat feel, it can spin within the length of its hull, although it is not truly sport-boat quick.

The 26RK moves through tacking maneuvers quickly and will track to 45 degrees true wind without effort. Downwind, the boat requires a fair amount of attention to hold a course. Although some consider the boat under-can-vased, its sail area/displacement ratio of 18.45 is still above that of many cruisers. Blue Dancer has a 130 percent genoa, while stock is 110 percent.

I found it better to steer from the stern pulpit seats than from the longer seats. Because the wheel is high relative to the leeward seat, I found it uncomfortable trying to steer in this position. Also, the transom helm seat seemed a bit too far away from the wheel for comfortable steering. Standing at the wheel feels very natural. If using the starboard pulpit seat to steer, the backstay is a bit intrusive. It was easy enough to move around the wheel to access the sheets.

The helm feel is mildly stiff, typical of a transom-hung rudder. Fortunately, it tracks very straight, particularly to windward, so well that the steering can be friction locked for long periods without wheel input. Visibility is great from any position, as the headsail and main both are cut high at the clew. The boom angles up, creating good headroom for standing in the cockpit and improving visibility at the helm. I did not see a provision for an emergency tiller, but it would not be difficult to fabricate one.

We collected some weed while underway. Lifting the rudder cleared it, while backing up cleared the keel. A majority of 26RK owners seem to prefer deploying the keel and rudder at midpoints.

To raise or lower the keel, you pull one of two lines that lead to a rotating switch at the battery-powered lift winch. It is rather noisy but doesn’t take long. There’s also a manual override in case you lose power, although a battery-pow- ered electric drill can be helpful with this otherwise tedious job.

The unusual vertical shaft in front of the mast has a large removable pin that locks the keel in place—whether up, mid-keel, or down—in case of a winch cable failure. This shaft also serves as a base for the gin pole when raising the mast.

Should one run aground, getting going again is as easy as pulling a cockpit line that operates the keel winch. Up it comes and away you go. (I use this technique on my MacGregor 26D to explore shallow areas and snug anchorages.)

The rudder is easy to raise by hand, but one must stand on the transom to do so. With the newer design, a lever locks the blade into place with notches at the trailing edge. Older versions had a locking pin. In either case, it must be done with prudence in a seaway; falling overboard would be easy during this operation.

All boats with a lifting keel, daggerboard, or centerboard that do not have a stub keel will suffer in docking maneuver- ability if some of the board/fin/ keel is not extended. Even then it is less predictable than a boat with more bite on the water. With rudder and keel retracted, they will handle like paddling a canoe solo from the stern in a wind. But then again, you can back up to the beach and sometimes step off without getting a foot wet. In calm water you can also use the keel as a temporary anchor; drop it into the muck and the boat will stay put until you raise it.

Conclusion

When the Seaward 26RK was introduced, the base price was a mere $29,900, intended to get folks of modest means into a Seaward boat. However, the model had an extensive options list that could nearly double that price, and many have all that and more. Being a good quality boat, it tends to be a keeper with its owners, who often upgrade hardware, sails, and electronics.

A brief online search found two 2005 boats listed for $39,500 and $49,900, and several newer boats ranging quickly upward, with a 2018 listed for $99,900—about the price of a new boat. So, these are not inexpensive fixer-uppers. They are boats for a specific mission that they accomplish well.

Allen Penticoff, a Good Old Boat contributing editor, is a freelance writer, sailor, and longtime avia¬tor. He has trailer-sailed on every Great Lake and on many inland waters and has had keelboat adventures on fresh and saltwater. He owns an American 14.5, a MacGregor 26D, and a 1955 Beister 42-foot steel cutter that he stores as a “someday project.”

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com