… and two more proper little yachts

Issue 127: July/Aug 2019

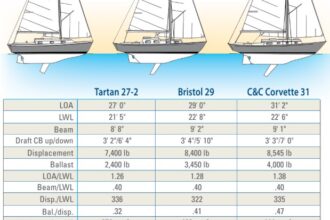

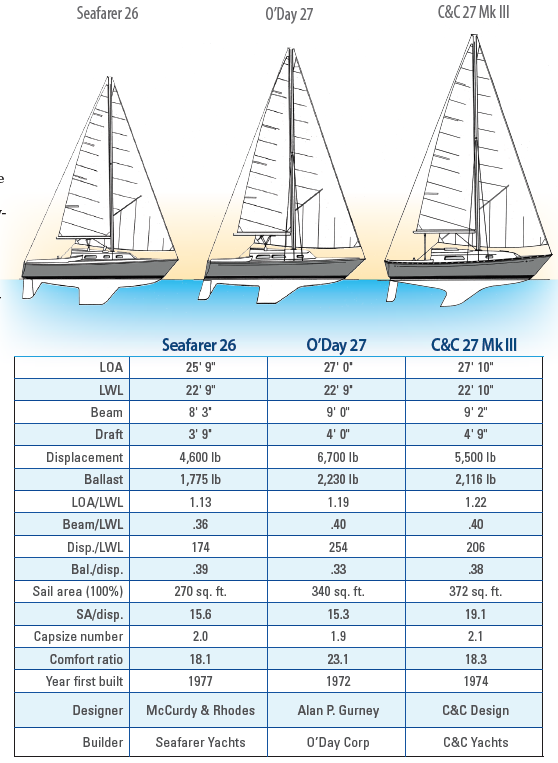

The McCurdy & Rhodes-designed Seafarer 26 is a proper little yacht, with full standing head-room, an enclosed head, a full galley, and sleeping accommodations for a family of four. It’s therefore appropriate to compare it to two other proper little yachts from the 1970s, the Alan Gurney- designed O’Day 27 and the Mk III variation of the popular C&C 27.

The C&C was a major retooling of its Cuthbertson & Cassian-designed Cruising Club of America (CCA) predecessor under the guidance of C&C’s chief designer, Rob Ball. The purpose was to make her more oriented to the International Offshore Rule (IOR) and qualify for a ½ Ton rating. This was accomplished by increasing the sail plan, paradoxically reducing the ballast, adding “bumps” at the measurement points, and updating the stern and rudder. The 6-inch increase in length that resulted pushed the LOA to almost 28 feet.

Note that the published LWLs of the three compared boats are within 1 inch of each other, which is probably as good a way as any to say that they are all the same “size.” However, the choice of criterium (dimension) for grouping boats of similar size has always been contentious, with the British traditionally using displacement or “tonnage” as the equalizer, and marketing people usually reverting to overall length as the criterium. LWL has always been the racing criterium in North America, where most rating rules have been formulated to achieve an approximation of LWL for handicap calculations.

In the tradition of the proper little yacht, each boat sports a fixed keel and an inboard, rather than transom-mounted, rudder. The LWL dimension can be artificially lengthened by the addition of a skeg over the rudder, which I expect is the case for all three of these boats. A transom-mounted rudder is never included in the measured LWL, but a skeg that fairs the top of the rudder to the hull is normally included. This skeg extends the LWL without adding any meaningful volume. As an example, the LWL for the earlier versions of the C&C 27 was 22 feet 2 inches, a full 8 inches shorter than the published LWL of the C&C 27 Mk III. At C&C, we got around this dilemma by listing the DWL (designed waterline length) as well as the LWL that included the skeg. The former was the actual distance between design stations 0 (the forward end of the waterline) and 10 (on these boats, the center of the rudder stock), and thus a better indicator of the length of the distributed volume of the hull. Needless to say, a longer LWL was a valuable marketing asset.

Each of these three designs has a deep sheltered cockpit from which to work the boat. These are boats you sit in not on, reflecting their proper-little-yacht character. However, only on the C&C was an inboard engine standard. The Seafarer and the O’Day mounted outboards instead.

Each of these boats also sets a sail plan heavily influenced by the later CCA and early IOR, with large foretriangles, overlapping headsails, and narrow “ribbon” mains. While Allen Penticoff, in his review of the Seafarer 26, maintains that 26-footers in general are well-suited to singlehanded sailing, these masthead rigs aren’t ideal, although a 130 percent jib would partially alleviate that problem. They are certainly not self-tacking, nor is it easy to reduce sail.

Displacements vary greatly, with the Seafarer being a full 2,100 pounds lighter than the O’Day and 900 pounds lighter than the C&C. Those variations in weight on boats with essentially equal waterline lengths result in a spread in displacement/length ratios from a very competitive 174 for the Seafarer, to a still sprightly 206 for the C&C, to a more moderate but accept- able 254 for the heavier O’Day.

Sail areas also vary considerably, with an anemic 270 square feet for the lighter Seafarer and 340 and 372 for the heavier O’Day and C&C. Thus the sail area/displacement (SA/D) ratios for the lighter Seafarer and the heavier O’Day are almost equal in the 15 range, but the C&C’s is a much more competitive 19.1.

There is no question that the heavier O’Day with a low SA/D ratio of 15.3 will stand up better in a breeze without having to reef early, while the C&C 27, with the highest SA/D ratio, will excel in lighter air, but will certainly be reducing sail first.

The capsize numbers are all at the high end, which is not surprising for boats of this size, as they really are not designed for offshore passages. These are three pretty little mini-cruiser/ racers. Maybe I’m biased, but to me, the C&C 27 is the prettiest of the three.

Rob Mazza is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. He began his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, working for Cuthbertson & Cassian. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new, and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com