Mark Sinclair’s choice for the solo nonstop race around the world

Issue 124: Jan/Feb 2019

“This retro race could not have come at a better time,” says Mark Sinclair about the Golden Globe Race 2018. “When I first read about it, I was exploring remote areas of Australia’s coastline in my S&S 41, Starwave, often singlehanded.” Within seven days of first hearing about the race, Mark had mailed in his entry, sold Starwave, and purchased the Lello 34, Coconut, for £20,000 ($26,000). “I’d watched a YouTube video of Coconut sailing in the Roaring Forties from South Africa to Adelaide,” he says, “and I was so impressed I didn’t look elsewhere.”

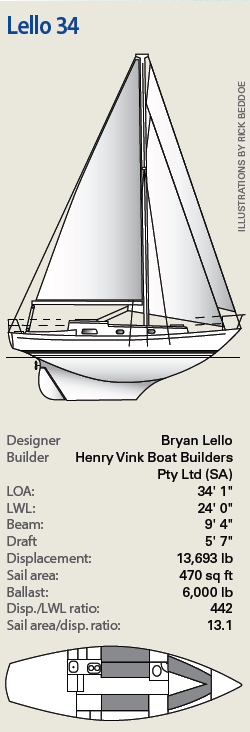

The Lello 34 is a traditional long- keeled fiberglass ocean cruiser/racer designed by South African Bryan Lello for cruising in the challenging conditions around the Cape of Good Hope and with the first Cape to Rio race in mind. This heavily built, narrow-gutted design displaces more than 7 tons in load condition, and with one of the highest sail area/displacement ratios in the GGR fleet, is clearly performance-oriented. Several hundred were built between 1966 and 1985. Early versions had a plywood deck and coachroof, but Coconut, built in 1981, is all fiberglass. Many have been cruised to all corners of the world.

But it’s one thing for a production sailboat to have a record of successfully completing long passages, another for it to sail non-stop around the planet — an endurance test like no other. Like the rest of the aged production sailboats competing in this race, Coconut would require well-thought-out modifications to ensure she is prepared to withstand the rigors of time and sea.

Mark is a recycler at heart and set about stripping Coconut with the aim of reusing as much of her gear and equipment as possible. He rebuilt her original Barlow winches, V-twin Farymann 22-horsepower diesel engine, mast, rudder, and Aries self-steering. Although he retained the original mahogany furniture, he removed the interior to fit new bulkheads. He also installed a smaller watertight deck hatch above the forepeak and replaced all the rigging, chainplates, sails, electrics, and safety equipment.

Hull and deck

Coconut’s hull and deck moldings were sound, but Mark was concerned about the power of green water. (Fifty years ago, the weight of water shifted the entire cabin trunk of Robin Knox- Johnston’s Suhaili). He set about reinforcing the hull-to-deck joint, and strengthened the coachroof with three sets of hanging knees. To protect the companionway hatch and provide some shelter for himself, he built a substantial doghouse over the aft end of the coachroof. The doghouse carries three solar panels, and two more are sited on the coachroof.

He glassed a plywood crash bulk- head into the forepeak, and a watertight main bulkhead beneath the mast fitted with an aluminum watertight door to close off the forward quarters. That the head remains just forward of the bulkhead is purely coincidental. He also replaced the compression post beneath the mast.

Mark retained the original mahogany furniture in the saloon, but modified the upper sections to carry storage boxes on the port side, and bookcases and a bank of batteries to starboard, to reduce the risk of their being flooded.

Mark originally positioned his life raft on deck, forward of the mast, but later built a wooden shelf for it in the after part of the cockpit. In this, he followed the lead of other entrants who adapted space within a cockpit locker following the experience of Australian Shane Freeman, who abandoned his Tradewind 35 after it was capsized and dismasted west of Cape Horn while en route to the start of the race. The broken mast damaged the life raft casing, leaving Freeman unsure that the raft would still inflate. He cited this as one of the reasons he chose to seek rescue from a passing ship and abandon the boat.

Mark had some stainless steel cleats (king posts) and solid fairleads fabricated. These encase the stern quarters and protect them from damage. To make a stronger enclosure around the deck perimeter, Mark replaced Coconut’s upper lifelines with a stainless steel tubular rail connecting the pulpit and pushpit.

Rudder and self-steering

Mark found on close inspection that Coconut’s rudder was in bad shape. Particularly troubling were cracks in the welds between the stock and the framework that supports the blade. He replaced the stock but had the original framework welded to it. Then, using one of the original sides as a base, he filled the interior space with high-density foam as a core and encapsulated the entire rudder with fiberglass.

He has also made a novel emergency rudder that deploys inside the windvane. Two fiberglass cheeks have gudgeons that slip over a pintle bolted to the stern in a cassette-type arrangement. Into that, Mark inserts a dagger- board rudder foil, which is then held in place with three “nutcracker” screws on one side. A 2-meter-long emergency tiller bolts into the top of the cassette.

Ever keen to recycle, Mark has retained Coconut’s original Aries windvane self-steering. He returned it to the factory in the Netherlands, where it was identified as being at least 40 years old, so it may well have been secondhand when installed on Coconut. It has been around the world at least once, but the aluminum components and stainless steel framework were sound, so Aries simply replaced the bearings, control lines, and blocks and pronounced it all “as good as new.”

Mast

Mark retained Coconut’s original mast extrusion after an examination showed it to be sound, but he has modified and strengthened it. He changed the single-spreader configuration to one with double spreaders and stiffened the mast’s sidewalls with riveted-on strips cut from an old mast.

He had new halyard sheave boxes made for the top of the mast and the base of the mast, and fitted a new gooseneck and a staysail sheave box. He replaced the shroud tangs on the mast and bolted much stronger chain-plates to the outside of the hull.

All the halyards and control lines now exit from the bottom of the mast and lead aft to winches and clutch stoppers sited inside the doghouse, where Mark can tend them without leaving the relative safety of the cockpit.

The final job was to rivet aluminum steps up both sides of the mast to facilitate going aloft to inspect halyards and rigging for chafe and damage.

Winches

The Barlow winches were in poor condition. The pawl housings had cracked and were so badly worn that the pawls often fell out and jammed the gears. The drums were fine, so rather than replace the winches, Mark had his local motorcycle engineering shop produce new pawl housings from a better grade of bronze. They are splined to bind onto the original stainless steel shafts. The shop also produced spares for him to carry on the GGR and plenty of pawl springs, which Mark has found have a tendency to go “peow” and fire off into inaccessible places or straight over the side when he disassembles a winch for service.

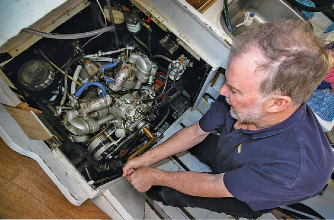

Engine

The Farymann 22-horsepower diesel engine had clearly seen huge use over the years, but rather than replace it, Mark chose to have it rebuilt. Because of a hole in the cylinder head and badly pitted valves, the top end of the engine had to be rebuilt, and with new piston rings, valve seats, alternator, and water pump the engine performs like new.

“The Farymann is a great piece of German engineering — some would say over-engineered,” says Mark. “Now, she starts first time, runs beautifully, and should be good for another 35 years.” The engine is mandatory safety equipment in the GGR, but after he motors out to the start line, Mark says it won’t be in gear again unless the proverbial hits the fan.

Under the GGR rules, competitors can use their engines in gear during the race, but are limited to carrying 40 gallons of fuel, so they have to balance motoring in periods of calm with the need to recharge batteries.

To reduce drag when sailing, Mark replaced Coconut’s original three-blade prop with a folding prop.

Navigation

The GGR sailors are restricted to using traditional navigation tools — sextant, chronometer, paper charts — and writing up their logs by hand. The golden rule is simple: if Robin Knox- Johnston couldn’t have it on Suhaili in 1968, then it is not allowed.

That cuts out electronic self-steering, GPS plotters, and anything digital, including calculators, chronometers, computers, and even iPods. “I was brought up in the Navy relying on a sextant and logarithm tables, so I’m quite happy with this,” says Mark.

Indeed, in keeping with this traditional culture, he has armed himself with two classic timepieces: a 1946 Hamilton 48-hour deck watch and a 1904-vintage Waltham eight-day chronometer. “I had both disassembled and serviced by a watchmaker in Adelaide, who cleaned all the small parts, removed the old mineral oils that tend to thicken and harden over time, and reseated everything in a modern synthetic oil that remains just as viscous in cold weather. Both have been carefully calibrated, and now the Waltham is running just 1.5 seconds fast per day and the Hamilton gains 3 seconds a day, which is easy to account for.”

Organizers of the Golden Globe Race 2018 approved only a short list of seaworthy production sailboats to compete in this solo nonstop around-the-world race. This list included the Westsail 32, Tradewind 35, Vancouver 32/34, Baba 35, Cape Dory 36, Rustler 36, Hans Christian 33T, and Lello 34. All of the 17 sailors who started the race worked hard to ensure their boats were ready to withstand the months of punishment that the Southern Ocean was sure to inflict. Here we take a close look at some of the pre-race modifications made by a couple of sailors, so we can learn where they thought their production sailboats were most vulnerable.

Barry Pickthall is the former yachting correspondent for Britain’s The Times and Sunday Times newspapers. A lifelong sailor, he trained as a boatbuilder and naval architect before turning to writing about the sport he loves. Barry lives in the UK and owns a classic wooden Rhodes 6 tonner, built in 1965, which he has faithfully restored to her original state. As a teenager, he was an avid follower of the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race, and has been instrumental in setting up the current GGR 2018 celebrating the 50th anniversary of Sir Robin Knox-Johnston’s victory and achievement in becoming the first to sail solo nonstop around the world.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com