Those nightmare threads that become unthreadable can be avoided

Issue 122: Sept/Oct 2018

Sailing is all about feel. And sometimes it’s through feel we get the first hint that things are about to go all pear-shaped . . . that funny feeling when the helm goes light because the rudder is ventilating and a knockdown is imminent unless you blow the chute, right now. On a beach cat, it’s the gust that is followed by slight lift in the transom, indicating that she’s about to dig in and pitchpole unless you bear off hard and get both feet under her.

So it is with nuts and bolts — every fault has a different feel, and the experienced hand can differentiate between threads that are dirty, bent, too tight, corroded, crossed, or on the verge of stripping or . . . galling. Continue tightening after any of the danger signs present, and ruined hardware will likely be the result. With threads, there are situations to be avoided, precautions to be taken before tightening begins, and measures that can be taken once a job is in progress.

Most of us have encountered static corrosion-based seizing, which results from expanding corrosion products filling the thread clearance and jamming the fitting or the nut. It also roughens the surfaces of the mated threads. Prevention consists of avoiding certain metal combinations, using a good anti-corrosion product on the threads, and in cases where the bolt or nut sticks anyway, spraying on the PB B’laster and waiting. A few good smacks on the bolt head with a hammer might loosen the corrosion.

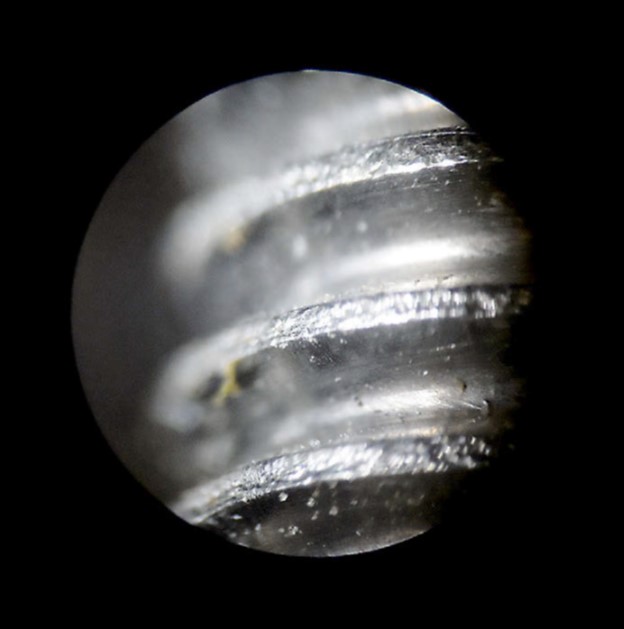

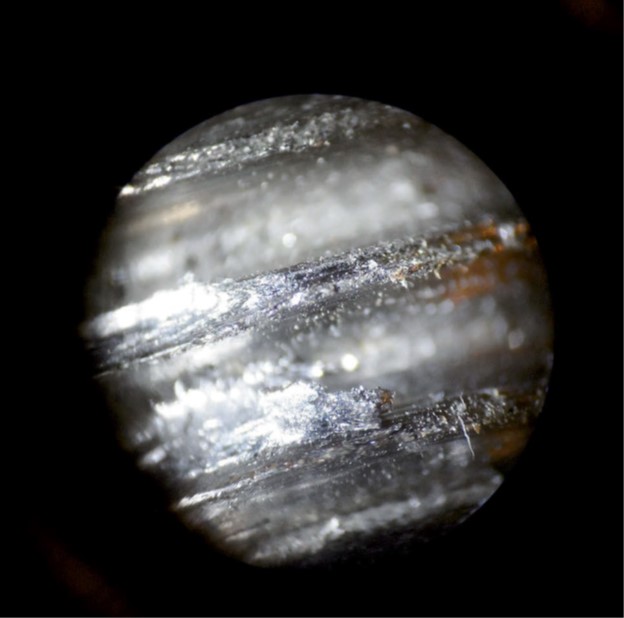

Galling is distinct from corrosion-based seizing in that it occurs while the nut is moving. On the microscopic level, metal surfaces are never perfectly smooth. So long as the loads are moderate and there is lubrication, the microscopic peaks slide over each other without significant damage. However, in the case of metals that are protected by hard oxide films, when the film begins to shear off, debris accumulates in the low areas. When too much debris clogs the threads, they will gall because, as friction increases, heat builds, and bits of good metal begin to tear away from the threads, often virtually welding the parts together. Aluminum, stainless steel, and titanium are all prone to galling, but less susceptible metals, including hardened steel, can fail if enough risk factors are present.

The classic trouble spots for sailors are turnbuckles, swageless rigging terminals (Sta-Lok and Norseman), and Swagelok tubing fittings, because all these threaded connectors are turned under high load for a considerable distance. Fortunately, if as many of the causal factors as possible can be eliminated, galling is avoidable.

Smooth the threads

Before installing a fitting, test-fit it by hand, looking for an easy fit without binding. The threads should not be overly tight or damaged. Female threads are cut with a tap, and the threads can be rough if the tap was dull, improperly lubricated, fed too fast, or if the tap drill was too small. Male threads, which are typically formed by rolling, are stronger, smoother, and can often be identified as slightly larger than the stud diameter. Run the threads together as many times as required until they turn smoothly.

Clean the threads

Even traces of salt and lime greatly increase friction as the threads come under load. Old fittings have a thicker oxide film, and polishing the male part with a wire brush can help.

Lubricate the threads

Any grease will help, but the best choices are high-viscosity products that offer good corrosion protection and high wash-out resistance. In practice and in lab testing, LanoCote, Tef-Gel, and Loctite Marine Grade Anti-Seize get high marks. Avoid non-marine anti-seize products, because these often contain metals, which in a marine environment will lead to increased dissimilar-metal corrosion. Loctite 242 is a good solution for swageless rigging fittings, as it lubricates while ensuring they stay tight.

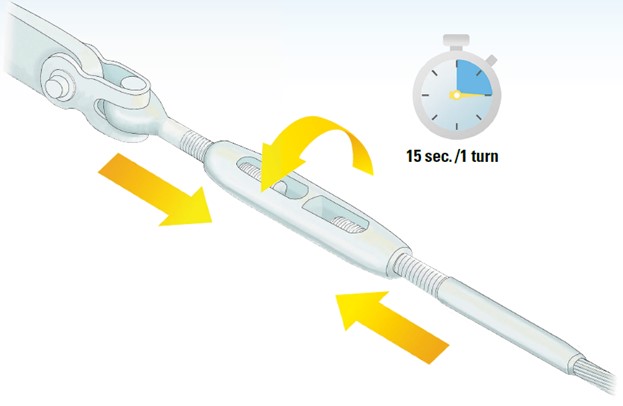

Slow down

Friction causes heat. Even when a hand wrench is used, a nut can become too hot to touch on the outside if turned under high tension for more than a short distance. Imagine how hot it is in the contact zone. Fifteen seconds per revolution may seem slow, but is common engineering advice for turnbuckles and fittings that are adjusted under load.

Tightening an all-stainless-steel turnbuckle slowly — taking 15 seconds or longer per turn — reduces heat buildup and lessens the chance of galling.

The effect of heat

Frequent exposure to high temperatures — engines, for example — increases risk by thickening oxide coatings and because of extreme pressures resulting from thermal stress. Although I recommend only marine anti-seize products for most boat applications, conventional products are effective on the engine, because heat generally boils out the water.

Relieve tension

Threads are not intended for pulling parts together. One of the most commonly encountered galling failures on sailboats occurs in turnbuckles. Tuning the rig requires turning the threads while they are under significant load, which is not something standard bolt threads are good for (acme threads, such as those found in vises and jacks, are designed for this). Before adjusting a turnbuckle, remove as much tension from the rigging wire as possible. Often this can be done by simply clipping a spare halyard to the chainplate and winching it tight. For tubing fittings and swageless wire terminals, the best we can do is lubricate and tighten slowly.

For common bolting applications, try bringing the parts as close together as possible first, so that no more than fingertip pressure is required until the last turn. If the application uses multiple bolts, bring them up evenly so that none are tightened under high load until the last turn.

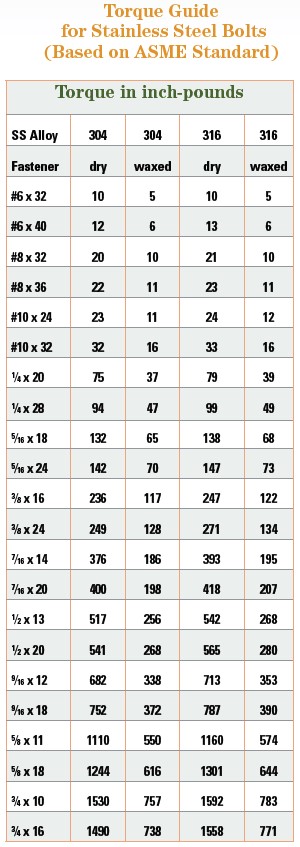

Do not exceed the recommended torque. Yes, the bolt will hold more than that, but stainless steel is already at risk of galling at these values. If your gut tells you it needs to be tighter so it doesn’t come loose, use a second locking nut or a thread-locking compound, or consider a larger bolt.

Choose coarse threads

Although fine threads allow for fine adjustment, they make little sense in stainless steel. There is less room for corrosion products and oxide breakdown, and they are more prone to both galling and stripping. Use coarse bolts where there is a choice.

Working with longer threads

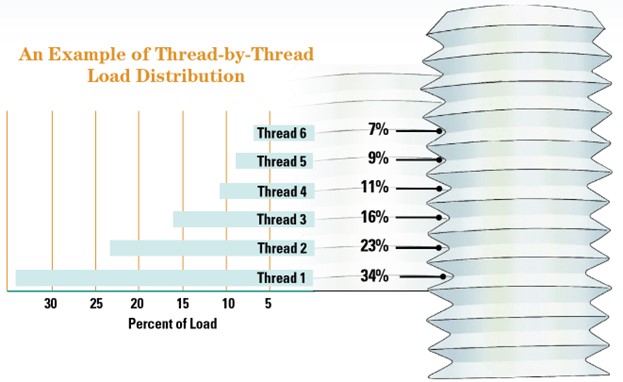

Turnbuckle threads are much longer than standard nuts on the theory that this reduces loading per unit area and allows adjustment under load. This is largely myth (see illustration “An Example of Thread-by-Thread Load Distribution”). Because the bolt stretches under load, only the first four to six threads carry any material portion of the load; the rest are just along for the ride. It’s sort of like playing tug-of-war with a rubber band — it’s hard to share the work if you can’t move your feet (the turnbuckle barrel is thick and does not stretch as much as the stud.)

If you have a nut that simply must be tightened for a long distance under load, lube it well, and use two nuts threaded on until they are just touching. Tighten the second nut just until the flats align within the wrench (with a 12-point box wrench or socket they can be half a flat off) and tighten the two nuts as one. This doubles the thread area, reduces the point load some, and is often enough to prevent galling and stripping. I’ve used this cheat in many tests where I’ve purposely over-tightened bolts over considerable distances to test backing plates, washers, and cored-composite strength. In general, the bolt will break before it galls or strips.

Bronze is better

Sailors are lectured to avoid dissimilar metals wherever possible, but this is the exception. Bronze turnbuckles with stainless steel studs are well proven in rigging applications. For the most part, open turnbuckles are usually bronze or chrome-plated bronze, and closed-body turnbuckles are 316 stainless steel, but check to be certain; some open turnbuckles are stainless steel, and some closed-body turnbuckles have bronze inserts.

In general, stainless steel turnbuckle bodies are only suitable for small-boat rigs and lifelines, neither of which need to be tightened under high loads.

Mixing stainless steel alloys is also a possibility. Using 304 nuts on 316 stainless steel bolts reduces the likelihood of galling while allowing the more corrosion-resistant material to be used for the bolt.

Hot-dipped galvanized nuts

Although this is a slightly different problem, it’s worth mentioning. Hot-dipped galvanized nuts have greater thread clearance to allow for the coating and for any corrosion products that may accumulate. Using zinc-plated nuts with hot-dipped bolts is a sure recipe for seizing, either during installation or within a few years. Always match hot-dipped with hot-dipped.

Like preventing sailing mishaps, avoiding galling is about taking a few preventive steps based on understanding the cause.

Galling in Turnbuckles — Jeremy McGeary

My first encounter with galling was in 1976 when I was working at Gulfstar Yachts, which Vince Lazzara, an early investor in Columbia Yachts, founded in St. Petersburg, Florida, after his non-compete agreement with Columbia expired.

Gulfstar’s first boats were motorsailers and trawlers that used the same hulls. Lazzara’s aim, in the time of oil embargoes, was to lure customers from his previous venture, Sea Rover houseboats, into sailboats. His next move was to design “proper” sailboats, and when he started selling the Gulfstar 50 into the charter fleets of Stevens Yachts and The Moorings, he knew he had reached a more sophisticated market, and took steps to improve the quality, and the perception of quality, across the Gulfstar line.

One way he did that was to use hardware and fittings from manufacturers with good reputations, and among those fittings were Navtec stainless steel turnbuckles. It wasn’t long, though, before he began to receive complaints from Gulfstar dealers who, when rigging boats they had sold, were running into problems with the turnbuckle threads galling. Gulfstar’s rigger encountered the same problem at the company’s commissioning yard. Lazzara was displeased, and the upshot was that Navtec subsequently supplied turnbuckles with stainless steel bodies and bronze studs. Problem solved.

Drew Frye draws on his training as a chemical engineer and pastimes of climbing and sailing when solving boating problems. He cruises Chesapeake Bay and the mid-Atlantic coast in his Corsair F24 trimaran, using its shoal draft to venture into shallow and less-explored waters.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com