A professional yacht designer says you might be happier with one

The summer winds are fickle and light in many of the waters of North America. I’ve sailed in a number of them: Lake Ontario, Long Island Sound, the Chesapeake, and the Pacific Northwest to name a few. It’s quite common in these waters to see cruising sailboats motoring along contentedly with their sails neatly furled and covered, rather than bickering with vagrant and weary breezes and the contrary tides.

In the Northwest it’s not unusual to see skippers motoring even when the wind is fair as, in the many miles of narrow channels and reaches, an adverse tide will often carry the yacht to leeward faster than the breeze can move her to weather! Other skippers will use the engine and sails in combination in order to obtain the maximum possible performance since tacking up one of these channels can be an exercise in futility when the tide is strong against you.

These owners are using their auxiliary cruisers as if they were motorsailers. Many of them might be happier if they had a true motorsailer, as it would offer the type of cruising they prefer. Motorsailers are not necessarily sluggards under sail either. Many perform as well as a typical ocean- going auxiliary cruiser, while at the same time offering more comfortable accommodations and a well-protected helm in an all-weather pilothouse.

In 1969 I sailed a TransPac race aboard Mystic, a 56-foot ketch-rigged motorsailer of my design. During the race we ate three hearty meals every day (including roast beef with York- shire pudding), enjoyed a friendly happy hour during the first dog watch, and were able to lounge and relax on her broad quarterdeck when off watch. We were still eating three squares a day when it blew a gale.

Motion fatigue

Other boats were reporting spar or rudder damage and “crew fatigue” (a euphemism for “seasick enough to die”). The result was a rested and contented crew that pushed Mystic hard. With strong and favorable winds, we were able to finish second in Class B, and that’s not bad for a clipper-bowed, full-keeled motorsailer with a raised poop deck and a great cabin aft, racing against some fast fin-keeled speedsters.

Power/sail combinations are not new, of course, and the oared galleys of the Mediterranean carried Phoenicians, Greeks, Turks, and Romans for well over a thousand years on trading missions and military expeditions. The Vikings further perfected the oceangoing power/sail vessel and traveled as far as Greenland and North America in their light, but rugged, ships.

It wasn’t until the invention of the steam engine that the first motorsailers were developed, though. Then the navies, distrusting the radical new engines, insisted on a large sailing rig as backup propulsion on their fighting ships. These vessels, according to Douglas Phillips-Birt, a well-known British yachting writer, were “the worst powersailers the world has ever seen . . . of uncertain reliability under power and sometimes actively dangerous under sail.” Fortunately, we’ve learned a bit since those days so that modern motorsailers can combine the best of both worlds instead of being potential floating disasters.

There are some basic problems in the design of a successful motorsailer though, and these cannot be ignored. Essentially, the hull form desirable for efficient powering at higher dis- placement speeds (a V/L.5 of 1.34 or slightly above) requires a prismatic coefficient (Cp) of 0.63 to 0.64 and means a quite full stern with substantial width and depth. This is completely unsuitable for good all- around performance under sail, so auxiliary yachts generally have a Cp of 0.54 to 0.56, with finer ends, to suit their hulls to the varying speeds provided by the fickle wind. In essence, the hull shape desirable for an efficient displacement motor yacht is very different from that of a sailing yacht, so every motorsailer must be a compromise.

Ballast problem

A second problem is that of ballast. The offshore sailing yacht requires a good ballast ratio, at least 25 percent and up to 45 percent of the total displacement, to give it the stability necessary to stand up to a breeze. However, every pound of unnecessary weight detracts from a motor yacht’s efficiency and performance. In addition, the sailing yacht requires relatively deep draft to provide lateral plane for weatherliness. This adds to wetted area and increases resistance under power. This is one of the reasons that many early motorsailers were keel/centerboard yachts.

For these and other reasons, motorsailers come in a wide variety of types, depending upon the ratio of sail propulsion to power, from the 30/70 (30 percent sail and 70 percent power propulsion) to the 70/30, with many varieties of yachts in between these two extremes.

The 30/70 is primarily a motor yacht but will have considerably more rig than just a “steadying” sail, barely sufficient to slow the roll. The yacht’s primary motive power will be a husky engine, perhaps sufficient to drive her to a V/L.5 ratio of 1.34 or even slightly more. This requires a hull with a high Cp, in the 0.63 to 0.65 range, and such a vessel will resemble a displacement powerboat more than she will a sailboat.

Draft will be relatively shoal and ballast will be light or even non-existent so the yacht’s stability will be moderate. To keep the heeling moment commensurate, the rig will be of fairly small area and low aspect ratio, with a mainsail luff/foot ratio of 2.0 or even less. Actually such a sail develops higher thrust per square foot of area when the wind is abaft the beam than does a high-aspect-ratio rig (luff/foot ratio of 3.0 or more) so the low-aspect-ratio rig with its smaller heeling moment is doubly suited to the 30/70. The yacht will have the ability to sail off the wind and, perhaps, even reach along slowly in favorable conditions, but she will require her engine to assist the sails to drive her to windward.

Needs extra urge

A particularly nice example of this type is the 1949 Sparkman & Stephens design, Maraa. This ruggedly hand- some 40-footer achieved 10 knots under power and had a 1,000-mile range with her 500 gallons of fuel. However, her SA/D ratio of under 8.0 will not provide sparkling performance unless her husky diesel is supplying considerable extra urge.

A step up from the 30/70 is the 50/50, but in between these two we might see something like the Fisher 37 with a Disp./LWL ratio of over 400, 42.8 percent ballast ratio, and an SA/D ratio of only 9.25. We might call her a 40/60, but she will still require considerable engine power to contribute to her sail power for reasonable performance to windward. Even having the engine ticking over at a fast idle can make a substantial difference in reduced leeway and improved weatherliness. It is rather a synergistic effect as the drive of the engine increases boat speed which, in turn, increases the speed of the apparent wind and the propulsive power of the sails.

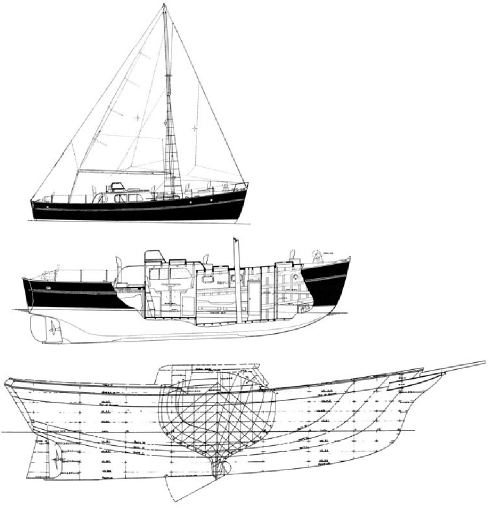

The 50/50 is an even closer balance of sail and power, and my 1970 design, the 44-foot centerboard ketch, Zig Zag, is one example of the type. She had a Disp./LWL ratio of 345, an SA/D ratio of 11 and a Cp of 0.56. Powered by an 80-horsepower diesel, this husky motorsailer toured the western world from the blue Danube to the Mississippi River and points between. She was equally at home in oceans, lakes, rivers, and canals.

From her builders in Holland, Zig Zag cruised to Denmark and then motored down through the canals to the Mediterranean, which she covered thoroughly from Constantinople to Gibraltar. A transatlantic passage took her to the Caribbean and from there she island-hopped to Florida, over to ol’ Miss and up that mighty river to Chicago.

The Great Lakes took her to the Erie Canal, and then it was down the Hudson to New York and up the east coast to Maine, where I had the pleasure of seeing her skipper again and having dinner aboard.

From Maine, she sailed to Florida once more and zigzagged through the Caribbean to the Panama Canal. At last, Zig Zag pointed her bows north, to finally arrive at her home port of Sacramento, nine years after her launch.

The Danube waltz

Her second voyage was equally ad- venturous involving a 90-mile journey on a flatbed trailer, from a German canal to the Danube. After that it was the Blue Danube waltz through Austria, Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Rumania to the Black Sea and back to Constantinople. It is fortunate that Zig Zag’s masts were tabernacle mounted, as the spars must have been up and down like fiddlers’ elbows on these land/sea voyages!

The 50/50 will often, like Zig Zag, be a centerboarder or perhaps sport twin bilge fins in order to keep draft shoal and still provide the lateral area necessary to minimize leeway. The hull will be finer and deeper than the 30/70, with a Cp in the 0.55 to 0.60 range, and will have a reasonable ballast ratio, say 20 to 35 percent, in order to carry a more efficient rig for windward work. Her sail area will be greater, with SA/D ratios of 10 to 12 and the rig taller, with luff/boom ratios of 2.5 or so. Such a vessel will sail to windward, tacking through 100 to 110 degrees perhaps and, when pushed with a fast idling engine, she might well surprise the skippers of pure auxiliary yachts.

Hoisting sail causes the boat to heel of course, and this can in crease resistance by 20 percent or more. The engine, running at a fast idle, can offset this increased drag and add considerably to the efficiency of the sail/power combination.

A well- designed 50/50, under sail and power, will point as high, make as little leeway, and probably produce as many knots as a good auxiliary cruiser/racer — and do it more comfortably. To many skippers, this is the best of two worlds.

Excellent performance

Between the 50/50 and the 70/30, we have motorsailers that can offer excellent sailing performance and have hull forms that are akin to the pure auxiliary in many ways. The 60/40 is represented here by my 1967 Mystic. This husky 56-foot center- board ketch has a Disp./LWL ratio of only 240, very low for her era; a SA/Disp. ratio of 15.5; and a Cp of 0.57. She often achieved V/L.5 ratios of over 1.6 when reaching and running in a good breeze and, with her board down, sailed reasonably to weather considering her shoal 6-foot draft. Mystic did not like light air though; her sail area was moderate and her wetted area was on the high side due to her long, full keel.

The 70/30 motorsailer closely resembles the pure auxiliary in hull form, general performance, and wind-ward ability. Indeed, the contemporary 70/30 will often be of fin-keel design and of moderate displacement with a good ballast ratio and a modern high- aspect ratio rig. The biggest difference between the pure auxiliary cruiser and the 70/30 seems to lie more with shallower draft, increased accommodations, and helm protection on the motorsailer.

The Scandinavian countries have produced some interesting production motorsailers. The late 1970s Finnsailer 38 is a good example with a low-wetted-area, fin- keel/spade-rudder hull of 263 Disp./LWL ratio. Her rig is low and the SA/D ratio is still on the low side at 11.6, so a big genoa will be essential for light air. But the hull should prove quite weatherly, and performance should be generally good.

My own impression of this yacht is that, given her 20,000-pound displacement and 11-foot 6-inch beam, she could readily carry a taller rig and another 150 to 175 square feet of sail. Actually, for windward sailing a high-aspect ratio rig, one with a luff/foot ratio of 3.0 or higher, is desirable for the efficient 70/30 motorsailer, as such a rig develops increased drive along with reduced side force when the wind is forward of the beam.

Higher displacement

Higher displacement

The modern 70/30 will resemble the auxiliary cruiser in most respects. She may have a slightly higher Cp, say 0.55 to 0.58, and will usually have somewhat higher displacement in order to carry the weight of a larger engine and fuel capacity. There will be more consideration given to helm protection, perhaps, and she will usually sport a centerboard, winged keel, or twin fins to keep the draft reasonable.

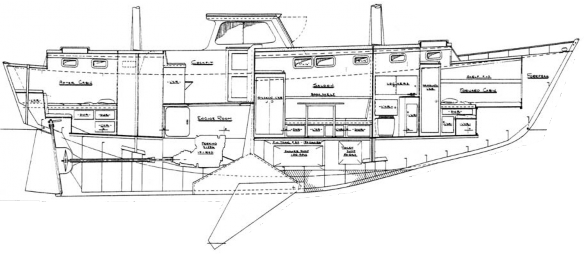

Indeed, modern pilothouse auxiliary cruisers, when designed with fin keels and given generous power, have all the attributes of a 70/30 motorsailer. I’m not certain whether Ahquabi is an auxiliary or a 70/30. Her 39,000-pound displacement and 5-foot 11-inch draft on a 38-foot waterline might well place her in the latter category despite the tall rig with 1,153 square feet of sail, and a 16.04 SA/D ratio. Perhaps we should call her a 75/25 or even an 80/20.

The amount of power required to motor the yacht along at or near hull speed can vary widely depending on the hull type, the waterline length, the displacement, and the speed required. Each design has to be considered individually. There is no simple answer. It is usual for designers to double the power required for a given speed in calm water in order to allow for the high seas and headwinds where good performance under power is so very desirable.

In any case, one of the problems of effectively powering a motorsailer has been that a large-diameter propeller turning at lower speeds is essential for maximum efficiency under power. Small diameter, high-speed egg beaters simply will not do the job. But that large three-blade prop is a tremendous drag when under sail alone.

This was a major problem 35 years ago and there were many discussions about whether to let the prop rotate freely in order to reduce resistance. However, this rarely decreases the drag and too often increases it. It can also damage the transmission. Don’t do it.

Special propellers

Today, the answer is a three-blade feathering propeller, such as the well- proven Brunton or the popular Max Prop. The usual folding propeller is relatively inefficient, but Gori has a three-blade geared model now that should suit many applications. For larger yachts there is also the old standby Hundested unit that has the propeller pitch adjustable from the helm through a hollow prop shaft. With this system the skipper can feed in the amount of pitch to suit the conditions. I’ve had a 45,000-pound yacht powered by a 30-hp Saab engine which did the job nicely when hooked up to just such an adjustable pitch wheel of large diameter.

One of the advantages of the motorsailer is its versatility. Zig Zag’s adventures proved to me that a good motorsailer can go virtually anywhere in the world and, indeed, can go places forbidden to a deep-draft auxiliary. So whether you want to cruise the canals, the lakes, or the oceans, a motorsailer of one type or another may well suit your cruising needs better than a more conventional sailing yacht.

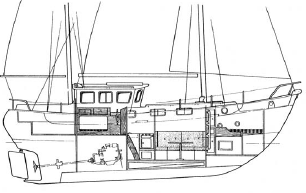

The profile of Zig Zag, above, shows a full keel/centerboard.