A close look at a modern practitioner of a very old trade

His voice had an easy, reassuring, and ageless quality about it. Brion Toss was calling back to clarify what work we wanted to have done on our boat. I explained that we were relocating our boat, Sirius, a 1997 J/32, from Lake Superior to the Olympic Peninsula and needed to get her re-rigged. But, beyond that, I wanted to have him review the vessel critically with this question in mind: What would you change if you were sailing this boat to Alaska?

“I like that,” he said and wrote us into his calendar.

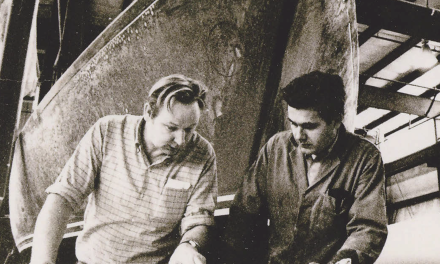

Working with Brion and his team of young riggers turned out to be a remarkably positive and unexpectedly educational experience. I met with Brion and Peter Bates to take the measure of Sirius’ rig. Two hours passed before I realized it. Brion’s enjoyment in teaching was evident from the first as he explained their observations and passed along many valuable tips.

He wore a vest of many pockets from which he pulled tools and materials: a Vernier caliper and small magnet to determine size and composition of the shrouds and stays and a 50x hand microscope (from Edmond Scientific) to examine the wire and swages for signs of corrosion or fatigue. Tip: by the time you can see cracks in a swage, there is no safety factor left.

Each tool was secured to Brion’s vest with a retractable lanyard. This way, he pointed out, you don’t do any serious knitting with the lanyards when working aloft. Another useful tip.

From yet another pocket came a ratcheting driver to extract a screw here and there to look for corrosion. Brion keeps a small syringe on an elastic lanyard loaded with Tef-Gel to lubricate the threads before setting them home again. Another good tip: this stuff seems to be the best corrosion blocker going, and it’s approved by Brion and the U.S. Navy.

Critical examination

Satisfied that the wire was all in good health and appropriately sized, we moved on to a critical examination of the mast, boom, and the roller-furling unit. They liked the Schaefer roller furler. Brion commented that they have very few field problems with them. The Schaefer units are also installer friendly and so the installations are more often done correctly than with some of the other popular models that they see on clients’ boats.

Next, we sat in the cockpit and examined the running rigging. Brion noted the stainless wire jacklines that I had installed in the cockpit just above the sole. He commented that the Sta-Lok fittings on them should be sealed as they are assembled, to prevent corrosion. And yes, the 3M 101 (polysulfide) I had aboard would work fine. Another good tip. Brion commented that a properly sealed and installed Sta-Lok or Norseman terminal has a longer service life than a swage. He is not a fan of swages.

We worked our way systematically to the foredeck, stopping to verify that the main and jib halyards were of appropriately low-stretch construction. Brion is quite fond of StaSet-X (New England Ropes) for these applications on cruising boats. This line offers lower elasticity and higher strength than Dacron double braid for only slightly higher cost and is relatively easy to splice.

Brion pointed out the relatively large distance between the bow chocks and their associated cleats. The larger this span, the greater the concern about chafe during cyclic loading of a nylon mooring line. I was cautioned to take preventive measures. One solution he recommends is splicing a length of Dacron line into the mooring line long enough to run from the cleat to well outboard of the boat. This takes advantage of the much greater chafe resistance of Dacron in the areas where chafe is of most concern, while retaining the elasticity of nylon for the rest of the mooring line.

Brion inspects the rigging on Ono with a 50x handheld microscope.

Stepping the mast

I was invited to join in the drama of stepping the mast, assisting Jennifer Bates with the backstay. She cautioned me that the legs of the bronze cotter pin I was securing should each be bent to about 10 degrees. (Brion’s gift for teaching flows through his team of younger riggers.) Bending the legs of the cotter pin through a large angle makes them harder to remove later and increases the chances of work-hardening or stress fatigue. The same is true of stainless-steel cotter pins. Yet another pointer.

Why bronze? Brion explained later as we were securing the rig temporarily with light tensions before Sirius was launched. The rig would be tuned to final tensions after she had been in the water for a couple of days. The bronze cotter keys are strong enough for temporary duty and easier to remove than stainless-steel pins. However, some would remain permanently. The toggles at the chain-plate end of the shroud turnbuckles were secured with bronze cotter pins. They are not subject to shear loads in this application and will hold up well. If the rig ever fails, it will be easier to remove the bronze cotter pin and drift out the clevis pin than to remove a stainless-steel pin or cut away the wire.

After the rig was tuned, the shroud turnbuckle studs were secured with stainless-steel tungsten-inert-gas (TIG) welding rod. This solution is strong, corrosion resistant, and neat looking. It has no sharp ends sticking out to snag lines or crewmembers. See Brion’s book, The Complete Rigger’s Apprentice, for a better description.

Floating gauges

The shrouds were tuned using appropriately sized Loos tension gauges, which had foam pads attached so, as Brion put it, when they go overboard they will float. The shrouds were taken up progressively, starting with the lowers and working up. The final step was what Brion called “ear boinging.” Two shrouds with the same dimensions (length and diameter) when tuned to the same tension should resonate at the same frequency. So when they are struck, or boinged, by hand or with the handle of a tool, they should sound the same pitch — another handy trick for skippers without tension gauges aboard.

Brion tightened turnbuckles by hand to near 10 percent of the breaking strength of the wire. He rotated the turnbuckle and wire terminal as a unit to tighten the lower thread then, holding the turnbuckle stationary, he tightened just the wire terminal by rotating it back the same amount. A quick, easy two-step motion. He pointed out that at about 10 percent tension, the wire will just begin to sound a pitch when thumped by hand. More good insights.

Brion indicated that a final tweak might be required after testing on the water. With a correctly tuned rig, the mast will remain straight (laterally), and the leeward shrouds will still have a taste of tension left when working to weather in heavy air. At the end of the afternoon, Sirius was ready to sail in better condition than ever, and I felt as though I had just attended a rigging course.

Sharing knowledge

Brion’s mastery of his craft is clearly evident, and he is remarkably generous in sharing this knowledge with students of all kinds. It is a rare combination. It all began with the Book of Survival, which focused on urban survival. It included among other things, two knots: a sheet bend and the square knot. Brion was about 17 or 18 at the time. Those two knots fascinated him, and he quickly learned to tie them.

He demonstrated his new skills to a friend, an accomplished sailor, who then handed him a copy of The Encyclopedia of Knots and Fancy Rope Work, by Raoul Graumont and John Hensel. It was, Brion recalls, a terrible book in terms of execution and presentation. But he fell into it like Alice down the rabbit hole. He spent months learning to tie them all.

Later, Brion’s mind began to turn to the question of why these knots existed and how to apply them. This led him into rigging and design and an awareness that ultimately all the forces lead back to the person at the helm. This people relationship still infuses his shop.

Brion became an apprentice under master rigger Nick Benton. It was a rather sporadic apprenticeship since Brion was living in the Puget Sound area where he had grown up, and Nick lived in Maine. Brion first worked with Nick in Port Townsend. He spent the first two Wooden Boat Festivals at Nick’s knee. His first hands-on work on a boat with Nick was aboard the gaff ketch, Flying Lady, in Anacortes, Washington.

The two were working aloft at the crosstrees. The yacht had not yet been ballasted and was swaying alarmingly, at least in Brion’s mind. Brion was beginning to look at adjacent slips to estimate whether they would land in the water or on a dock. To allay his fears, Nick discussed the principles of righting moments, lever arms, form stability, and ballast stability while continuing to work quickly and deftly on the project at hand.

Greatest gift

Brion recalled that Nick had a way of saying very basic things very clearly and then expanding on them over time. “Quality first, then speed.” Nick repeated this twice more for added emphasis then continued, “Once you have the rhythm of it, you can work on efficiencies.” Brion believes his greatest gift from Nick was that Nick set the bar so high.

Brion had the opportunity to spend about six weeks in training with him before Nick died in a rigging accident. Brion was teaching a rigging class in a boat shop in Maine when he heard the news. Even now, when he recalls that day, Brion becomes quietly contemplative.

The teaching of rigging was the only real disagreement between the two. Nick was from the old school, in which apprentices were discouraged from going out and widely sharing the knowledge of the master for fear that this would take food out of the mouths of the master’s children. Brion’s instinct was that it should somehow be good for the craft if more people were aware of the principles involved in the design and implementation of a good rig.

Included in Brion’s formative days as a young rigger was a six-month tour of duty aboard Sea Cloud, a four-masted bark, 300 feet on deck and setting nearly 15,000 square feet of canvas. He was recruited because of his skills in splicing and seizing wire rope and was expected to train a pool of riggers to sustain the ship. He also spent a winter in Galveston, Texas, helping to restore the bark, Elisa.

Brion lived and worked as a rigger in his own shop in Maine for about five years before returning to the Northwest. He set up shop in Anacortes in a ballroom in what had been the city hall. He shared the space with Emiliano Marion, author of The Sailmaker’s Apprentice. In 1979 the two of them promised that they would write their books: The Sailmaker’s Apprentice and The Rigger’s Apprentice.

Also retail

Brion subsequently moved to Point Hudson at the north end of Port Townsend, where he has had his shop for 15 years. Brion Toss Yacht Riggers usually has four or five full-time riggers, counting Brion. Five additional staff members manage the retail side of the business, do the accounting, and manage all the other aspects of running a business.

The retail side of the shop is unusual for a rigging business. They sell tools, some of their own design; books (Brion’s and others he recommends); training videos; and materials such as rigging tape, bronze cotter keys, TIG wire, Tef-Gel, and loggers’ tapes.

For many years, Brion’s writing subsidized the rigging operation. He readily acknowledges the important role that his wife, Christian, has played in changing Brion Toss Yacht Riggers from a hobby to a business. He also feels blessed to have an astonishing staff with great skills, including people skills and lots of enthusiasm.

About 75 percent of the company’s business comes from the Puget Sound area (including Vancouver and Victoria, British Columbia). The rest of the business is in North America or the Caribbean. Often they work on boats via email or fax; they get the data required to do rigging design and construction, then they package the materials for installation by others.

The wall of the rigging shop had clipboards for seven project boats when I stopped by to visit with Brion. They typically have between six and eight at a time. Brion is quick to point out that they get far too much work because of work which was poorly done originally. He feels that rigging is the single least regulated aspect of sailing; there are no meaningful standards by which to assess the training or competency of a rigger. This is one reason that Brion is actively helping SAMS (the Society of Accredited Marine Surveyors) and NAMS (the National Association of Marine Surveyors) to develop standards.

Optimum design

A practical definition of a rigger that Brion once heard is someone who can take a boat and rig it. Implicit in that definition is the knowledge to create an optimum design for a specific boat and its intended use and the hands-on skills to construct and install that rig. These disciplines form the core of the curriculum for his apprentice riggers.

Brion requires a two-year commitment from an apprentice. At the end of this time the apprentice becomes a journeyer. The journeyer knows how to measure the righting moment of a boat, can compute from this the loads on the rigging, can design an optimum rig including calculating the required mast section, and has the skills required to fabricate and install the rig.

Peter Bates was the first to complete this program and has chosen to stay on at Brion Toss Yacht Riggers, where he has become the rigging manager. In Brion’s view, a journeyer can be turned loose with little supervision, although he still has much to learn.

Apprentices are encouraged to get offshore experience, and several have crewed on yacht deliveries. Brion knows that the vigorous conditions of a difficult passage will help them gain a deeper appreciation of the forces that a rig must withstand.

When asked about opportunities for young riggers, Brion says that although many of his apprentices have gone on to rewarding positions, his journeyers are over-qualified for most rigging jobs available (which are not very rewarding anyway). He notes that people who fabricate rigging fall prey to machine capability and availability.

Most wire terminals today are swages, not because they are superior solutions (which they are not), but because the machines to produce them are readily available, the components are produced in volume at relatively low cost, and the operation of these machines is not usually viewed as a highly skilled task. This last point may be the reason for the excessively high number of banana-shaped swages and aircraft eye swages (instead of marine eyes) that Brion finds on clients’ boats.

Brion and Christian Toss enjoy the lighter side of life.

Industry trend

Brion sees the continued development of new fibers and ropes as an important industry trend. We may soon look back, he believes, and realize that the use of wire for rigging was a 150-year anomaly.

The part of his business that Brion enjoys the most is boat surveys. Every rig is a puzzle with many possible solutions. The best one must also integrate the owner’s needs and aspirations. He prefers that owners be aboard during the survey so that he can discuss his findings and suggestions for improvements as they go along. These clients can usually make more informed decisions than the ones who simply read the final report. He also enjoys the drama of stepping a mast, tuning a well-designed rig and watching the boat become a vessel — in the many senses of the word — for its owners.

Brion owns a Sam Crocker-designed catboat, which is moored in Maine. Since this is quite a commute, he does most of his sailing on other people’s boats. He tries to get offshore at least every four or five years. His interests, apart from boats and rigging, are wide ranging. He is a student of Aikido. He loves drumming — especially African and Caribbean — reads widely and loves his home whose renovation is receiving much of Christian’s boundless energy.

Brion’s classroom is the great out-of-doors on boats of all descriptions.

Brion the teacher

Brion is very serious about teaching the principles of good rigging. His efforts include books, magazine articles, training videos, presentations, and seminars. Brion has two books in print: The Complete Rigger’s Apprentice and Knots, a Chapman Nautical Guide.

Topics in The Complete Rigger’s Apprentice range from knotting and splicing, to rig design, loft procedures, installation, and maintenance. The introduction includes a summary of Brion’s rigging style: 1. Adapt the traditional; 2. Invent the new; 3. Work out the bugs. It was the result of integrating two earlier works The Rigger’s Apprentice, and The Rigger’s Locker. There are a lot of books on knotting and splicing, but Knots is a little gem. It encourages the reader to develop a personal list of core knots to address his specific needs.

Two more book projects are underway, jointly with his wife, Christian, with plans for a third one later on.

Brion Toss Yacht Riggers offers five two-day seminars each year. Most seminars are intended for boatowners. Some are geared toward the needs of riggers, delivery skippers, and other professionals. Brion limits seminar size to 10 students.

He has also created a wonderful series of instructional videos produced by Cruiser Guide Videos. They include: Tuning Your Rig, Inspecting Your Rig, Going Aloft, Installing Sta-Loks, and Making Eye Splices. His old love of knotting gets a chance to show off in Fancy Ropework, More Fancy Ropework, and Still More Fancy Ropework. He finishes off with String Magic in which the thespian in him takes the stage to dazzle the audience with rope tricks and teach how they are done.