Size evokes no envy when sailing is its own reward

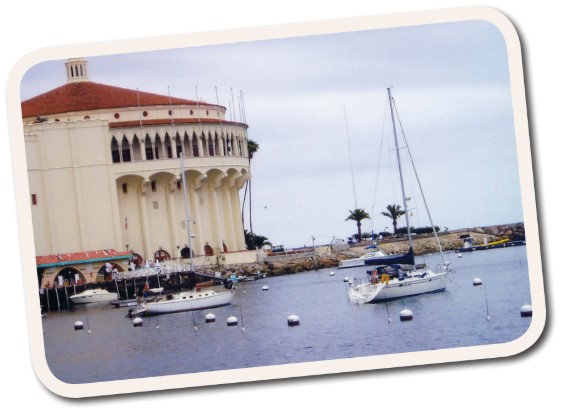

My wife, Jen, and I were settling down in one of our favorite anchorages after a hard but rewarding day of sailing. We’d broken out the margaritas and were enjoying the last of the hot summer day. Out in the lake, we could see another boat approaching our popular little bay. She was, as Jen likes to say, “a big girl” and obviously very new. She certainly was an impressive sight, her perfect white hull and sails gleaming as she slashed across Lake Champlain toward us. As she neared the entrance to the anchorage, she turned into the wind and her main and genoa simultaneously began to furl. “They must have electric furling,” Jen said.

I nodded in agreement, “I think they were on autopilot as they sailed up; I didn’t see anyone near the wheel.”

Sails furled, the boat turned into the bay. There was a spot open next to us, and her skipper steered her over. She towered above our 30-footer, her diesel barely making a sound. A nice looking couple in their thirties were in the cockpit. We exchanged waves, and a moment later their electric windlass began dropping their anchor. The couple fussed about the cockpit for a few moments, then disappeared below. The sound of a generator and air conditioner thrummed in the quiet little bay.

We wondered what they thought of us.

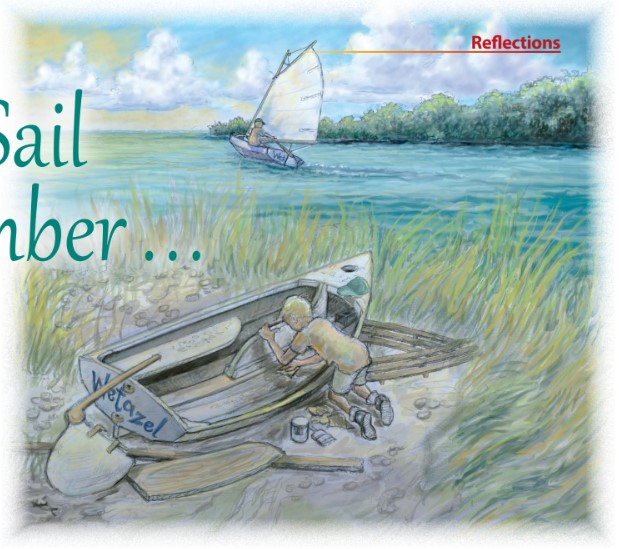

Almost off to the landfill

I should explain that our boat, Ismitta, was a week away from being cut into pieces by a chain saw and hauled off to the dump when we took ownership of her. She had been damaged in a hurricane and written off by the insurance company. Jen and I worked on her for two years before she was ready for the water. Every spring, we upgrade her a little more. Jen is masterful at restoring wood, and Ismitta’s brilliantly finished woodwork gleams. While Jen has applied her good taste and design skills to decorating our lovely little cabin, I have focused on the structural and mechanical aspects. We make a good team, and we’re proud of our boat and our accomplishments. However, our brave little vessel appeared a little shabby and quaint next to the gleaming behemoth nearby.

That afternoon and evening, Jen and I swam, chatted, got a little tipsy on margaritas, grilled our dinner, and gossiped about the goings-on in the anchorage. We then had a cutthroat game of rummy in the cabin before retiring. The couple next to us spent the day in the luxury of their air condition- ing. From the sounds and the purplish light that flickered from their ports, we imagined they were watching a DVD.

In the morning, as we were having coffee, they reappeared. Wishing us good morning, they pushed a button on their windlass and their anchor began to reel itself in. A few moments later, their sails unfurling as if by magic, they were off down the lake.

“That was a nice boat,” Jen observed.

Economic realities

For those of us with good old boats like Ismitta, certain economic realities play a role in our sailing experiences. Sometimes we find it intimidating to be in the proximity of the boats of wealthy people. Jen and I acquired Ismitta for complex reasons. We felt sorry for her; we liked how she looked, and we thought we could save her. But the primary reason was that a boat like her, in the condition she was in, was all we could afford. We could no more buy the boat that had spent the evening beside us than we could a Lear Jet.

These economic realities permeate sailing and the sailing community.

Socio-economic factors play a role in every aspect of what sailing is. Consider the spring rituals associated with getting our boats ready for the sailing season. Many of the lovely new boats at our marina are professionally maintained. As Jen and I labor over Ismitta, checking off items on a very long to-do list, we might see a car pull up to one of these boats. A couple emerges and looks things over for an hour or so. In a couple of days, a professional detailer shows up with buffers and wax and goes to work. Yard workers appear, scurrying over her hull. A couple of days after that, the cradle is empty, and the gleaming vessel is in the water. We labor on, partly because our boat needs more attention and partly because it takes us longer to do things than it does the professionals.

At our marina, the yard workers have been generous with their time as they explained how to do some of the trickier operations we have tackled. We like to think they have respect for people who are willing to do their own work. They probably feel sympathy when they see my skinned knuckles and grease-stained clothes. On the other hand, I recently did for less than $30 a repair to our engine for which the yard had submitted an estimate of $1,200. Jen’s remodeling of the interior and woodwork would have cost untold thousands of dollars.

Fellowship in labor

We work together, learning as we go, and we are slowly acquiring complementary and wide-ranging sets of skills and knowledge. We have found that our days spent getting Ismitta ready for the sailing season are nearly as rewarding as the days we actually sail her. Other owners of good old boats are there too, and the sounds of power tools in the air are joined by those of conversation and laughter. They come to visit us, to chat, to borrow tools, and to offer and seek advice. As Ismitta nears completion, Jen and I often step back and look at her on her stands, admiring our work and the beauty of our vessel. We have now sanded, painted, varnished, or otherwise reworked every square inch of Ismitta. She is now approaching the point where she is just the way we want her. We love her.

Altering the experience

The choices inherent in having a lot of, or very little, money have the effect of altering the essential experience of sailing. I believe these choices have both positive and negative aspects. While it might be nice to have other people do the dirty and unpleasant jobs associated with sailboat restoration and maintenance, we would have been denied the pride and pleasure that comes from doing something ourselves. The security that some feel from knowing a job was done by professionals is tempered by the fact that those folks haven’t acquired the skills to do it themselves, should the need arise. Having an advanced, highly automated boat means that you are not as involved in sailing her. And, at least for some sailors, these boats serve to isolate and disengage their sailors from the very things I treasure the most from the sailing experience.

That is the central point for me. How involved are you in your sailing? At what point do you evolve from being a sailor to being a passenger? I argue that one of the primary pleasures of restoring/maintaining/sailing a good old boat is the absolute level of involvement it entails. We know Ismitta inside and out. We are involved in every aspect of her existence. When we sail, we are a team of three — or maybe more accurately, a single entity.

Familiar rituals

An hour later, I went forward to lift the anchor as Jen started the engine. She has a little trick she uses to start the engine when it’s cold. This anchorage has a muddy bottom, and the anchor can get bogged down and difficult to extract. I have a little technique that I use to draw on the boat’s momentum to free it. I take the helm while Jen goes forward and hoists the sails.

Soon we were surging through the clear blue waves. We could see our evening neighbor on the horizon, a slash of white against the sky. “If we could trade Ismitta for that nice big boat, would you?’ I asked.

Jen turned to me, surprise on her face. “No! Ismitta is our child. She is not for trade and not for sale. Ever.” She paused, “Furthermore, don’t talk like that in front of Ismitta, you’ll upset her.”

Somehow, I doubt that the young couple over there on the horizon feel the same about their boat.