Blackberries, apples, and balancing stones grace a princess’ gift in the Salish Sea.

Blackberries, apples, and balancing stones grace a princess’ gift in the Salish Sea.

Issue 129: Nov/Dec 2019

Somebody reminded me the other day that my wife June and I have been cruising around Puget Sound and the northern islands in small boats for nigh on a quarter century. The inevitable question came up: “What is your favorite destination? Is there one particular moment that stands out in your memory?”

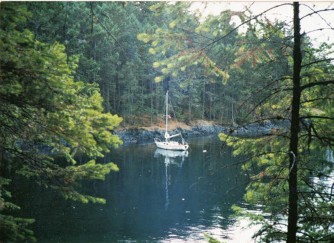

Well, as it happens, we don’t have a favorite destination. There are just too many wonderful anchorages that we’ve enjoyed to choose just one. But as for a particular moment, there is indeed one that still stands out, and it happened in a place that holds more than a little magic, British Columbia’s Portland Island.

The moment came just after anchoring. The island, green, silent, and mysterious, lay a few yards off our bow. The warm September sun struck sparks on the calm water. A snug, deserted cove wrapped itself around us like a blanket. In the cockpit, June caught her breath and pointed. An otter had poked his whiskery snout above water and was inspecting us quizzically. We stared back, as fascinated as he.

After a few moments, having decided we were harmless, he went back to work in the transparent water, catching fish and taking them ashore to dine among the rocks on a tablecloth of dark green seaweed. He was so close that we could see his teeth and hear the crunch of bones as he chewed.

Then he caught a fish, took it ashore, and left it untouched on a rock. He stared straight at us.

“What now?” June whispered.

“He’s saying ‘Grub’s up!’ ’’ I said softly. “ ‘Come and get it.’ ’’

“Yes, he’s saying ‘Welcome to Canada,’ ’’ June chuckled. “Just another friendly Canadian.”

We had experienced kindness everywhere on our first visit to British Columbia’s Gulf Islands in our 22-foot sloop, but not for one moment did we expect to be invited to lunch by an otter. We declined the invitation, of course, but it was a fascinating introduction to what turned out to be a bewitching island.

We’d been directed to Portland Island by Jen and Bernie Emms, old sailing friends we’d run across in Bedwell Harbor. We’d checked into Canadian customs there after a leisurely four-day trip from our home port of Oak Harbor, on Whidbey Island, about 60 miles north of Seattle, Washington.

The Emmses had invited us over for supper on their home-built 30-foot sloop Hepatica anchored nearby. Amid the good vittles, fine wine, and pleasant conversation, they told us of a deserted island where we would find blackberries and apples, balancing stones and oysters, purple starfish and a racetrack.

“Did Bern say something about a racetrack?” June asked as I rowed us back to Tagati under a blanket of stars. “On a deserted island?”

“Yes,” I said, “and bright purple oysters.”

“Starfish,” said June firmly. “Purple starfish. We’ll talk about it in the morning. Just try to row straight.”

The Canadian Sailing Directions are predictably gloomy about your chances of arriving at Portland Island in one piece. “Because of the dangers around it, Portland Island must be approached with extreme caution,” the good book says.

All I can say is that anyone in a small boat with a large-scale chart and an ounce of common sense should have no problems. The approaches to the two main anchorages are clean from seaward. We certainly had no problem entering Royal Cove, on the northern edge of the island, although it hid itself until the last moment, as usual.

It’s a popular spot for cruisers, just four miles from Sidney, on Vancouver Island, but it was deserted on the September Tuesday we arrived. We dropped an anchor over the stern in the southern recesses of the cove and took a line ashore from the bow to one of a series of iron rings set into the rockface at the shoreline’s edge.

Our otter continued to splash around the boat, playing and eating for more than an hour, despite our ungracious refusal to share his fishy meal. But after we’d eaten a human-type lunch in the sunny cockpit, another boat arrived. And although she moored a discreet distance away from us, our otter disappeared. We never saw him again.

After lunch, we rowed to a nearby dinghy dock and began our trek of the island. A marine park since 1967, it’s only about a mile long and a little less across — about 450 acres in all — exactly the right size for slow-but- steady explorers like us.

We meandered the northwestern trail along the island’s edge, a little- used footpath through tall evergreens interspersed with delicate deciduous trees. The main trail looped and wound its way past numerous bays, beaches, and inlets, all of them outstandingly beautiful, but we were often lured on to side trails leading to the headlands, where piles of balancing stones stood silhouetted against the bright glitter of the sea in the Satellite Channel.

They’re known to the Inuit as inuksuit and are often many feet tall, but these on Portland Island were more moderately sized. An abundance of small dark-gray rocks, all with good square edges and flat faces, made perfect geological building blocks for these intriguing stone cairns.

The first one we came across was three or four feet high, cleverly and patiently constructed on the cantilever principle. But a confirmed meddler like me can always see where a small improvement might turn a merely competent job into a wonderful work of art. “It needs a small wedge just here to change the fulcrum,” I explained to June. “Let’s see if we can find — ”

“I wouldn’t change it,” she said flatly.

“Why not?”

“We don’t know who built it. Or when. Or why.”

“You think it’s a sort of religious shrine?”

“Maybe.”

The thought that I might invoke the wrath of ancient native spirits dampened my ambitions. But not for long. “I’ll build one of my own,” I said. But the best place had been taken, and I couldn’t find another. Besides, the rest of the island was beckoning in the warm sunshine. “Maybe I’ll come back tomorrow,” I said.

“Good idea.”

We discovered later that although the island was once inhabited by Coast Salish natives, whose shell middens were still visible, the balancing stones were not ancient religious artifacts. They were simply erected by anyone passing by. And meddled with, undoubtedly, by the next passerby.

Golden plains of pale, dry grass smelling of sweet hay drifted down to the beach from meadows inland. We followed one eastward toward the middle of the island until we came into a large grassy clearing where an old cast-iron handpump reached deep into the earth for pure well water. Although it would not have been out of place in a medieval European village, it still worked perfectly, and we slaked our thirsts before heading south to Princess Bay harbor.

To our surprise, the trail turned into a newly repaired boardwalk for much of the way, and we enjoyed a wonderful lazy stroll side by side in the sunshine. Wildflowers blooming along the trail attracted bees and insects with gossamer wings. The air was laden with a spicy, sun-warmed smell we couldn’t identify, until suddenly we found ourselves among towering brambles quivering under loads of ripe blackberries.

We ate and walked, ate and walked, until we thought we’d burst. And then we came to the apple trees. Bent and ignored, untended and unpruned for decades, they still produced delicious apples. We had to taste those, too, of course, and kept a couple each to eat on the boat.

About half a dozen yachts dotted Portland Island’s pretty southern harbor, known as Princess Bay and also as Tortoise Bay, because of the Tortoise Islets that guard the entrance. We were glad we’d chosen Royal Cove, because while Princess Bay is larger and has more swinging room, it’s not as well sheltered, especially from the southeast, the direction of the frontal rain winds. A few people wandered the beach.

The island was a lot busier in years gone by. The Hudson’s Bay Company, which owned it, hired several hundred Hawaiians in the mid-1800s to work the land. The Kanakas, as they were known, quickly picked up the local Native Americans’ languages and acted as interpreters for the fur traders. Some of them decided to settle on Portland Island when their contracts came to an end, and to this day the most prominent point on the western coastline is known as Kanaka Bluff.

The person who really stirred the island up, however, was an ex-army officer. Maj. Gen. Frank “One-Arm” Sutton was a flamboyant character who earned his nickname demonstrating his bravery at Gallipoli, for which he was awarded the Military Cross. His was a restless nature, and he roamed the world looking for adventure and an opportunity to make a fortune. He found it when he was hired by a Manchurian warlord during the Chinese civil war.

He came back to British Columbia a millionaire, and he bought Portland Island. He quickly turned it into an estate worthy of an English country gentleman, stocking it with pheasant and other gamebirds, and building a stable and track where he could breed racehorses. One-Arm Sutton lived high on the hog for several years until the stock market crash of 1929 dragged him under, and he was forced to sell. The province of British Columbia bought the island in 1958 and presented it to Princess Margaret of Great Britain. She, no doubt prefer- ring her nice warm hideaway in the Caribbean, gave Portland Island back to the province.

On the way back to our boat, we took a small side path off the main track, and there we found the foundations of the major’s long-tumbled-down stables. Nearby, we could make out the shape of the oval track that had once been there.

The next day we took ashore a bucket, a bottle of shampoo, and two towels. We made straight for the well, where we sat down like two kids and washed our hair and some other regions that hadn’t seen a shower for a week. It felt simply wonderful, although the well water was ice-cold and gave us headaches. No matter, we spread out our towels and sat on the dry grass in the warm sun with our tops unbuttoned. Great gobs of shampoo foam lay scattered around, and we had no sooner got the place looking good and sordid when a large audience suddenly appeared — seemingly all of the crews of all of the boats anchored down south.

“Just washed our hair,” I explained lamely, gathering the towels and stamping on as many shampoo gobs as I could reach. “Lovely day, isn’t it?”

Their replies were muted, and they scurried past, averting their eyes, as if they were avoiding hoboes demanding a handout.

“City people,” I said when they were out of sight. “Still uptight.”

“Yes,” said June. “Haven’t been on the island long enough to relax.”

In our new, clean condition, we explored more that afternoon, trekking down to Kanaka Bluff and finding the rock pools full of exotic purple starfish that the Emmses had promised. There were delicious oysters, too, and I ate one straight off the rocks. I knew I’d probably go to jail if the oyster police ever found out, but at that particular moment I considered the risk justified.

That final evening at Portland Island, as we sat in Tagati’s cockpit drinking sundowners, we watched a real old-timer approach the mouth of the cove. She was the MariGladis, a 103-year-old gaff cutter, 35 feet on deck, a former Exmouth pilot cutter. She was in magnificent shape still, obviously carefully looked after and loved.

That final evening at Portland Island, as we sat in Tagati’s cockpit drinking sundowners, we watched a real old-timer approach the mouth of the cove. She was the MariGladis, a 103-year-old gaff cutter, 35 feet on deck, a former Exmouth pilot cutter. She was in magnificent shape still, obviously carefully looked after and loved.

“Wouldn’t it be nice — ’’ I began.

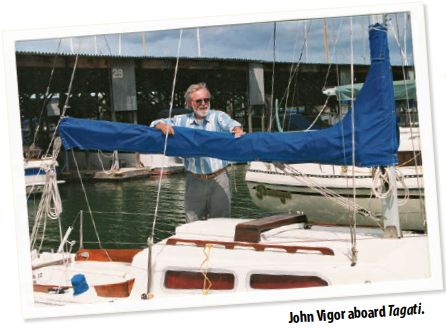

“No,” said June. “Don’t say it.” She patted the coachroof gently. “Tagati has done us very well. She’s a lovely boat.”

But we both knew this was our last cruise in her. After three seasons of nautical backpacking in Puget Sound and Canada, we felt we had done our time. We were looking for something we could stand up in to put our pants on. We had our eyes on a little Cape Dory 25D that might fill the bill.

If it all worked out, we told ourselves, we’d go back to Portland Island in a little more style. At least, we’d have 20 gallons of fresh water on board, so we wouldn’t have to wash our hair out in the open and scare the visitors.

John Vigor, a former newspaper columnist and editorial writer, is the author of 12 sailing books. John was on the Good Old Boat masthead at its inception and helped to guide the magazine through its first decade. He is a retired sailing and navigation instructor who lives in Bellingham, Washington. He can be found at johnvigor.com.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com