A Traditional Masterpiece

Issue 129: Nov/Dec 2019

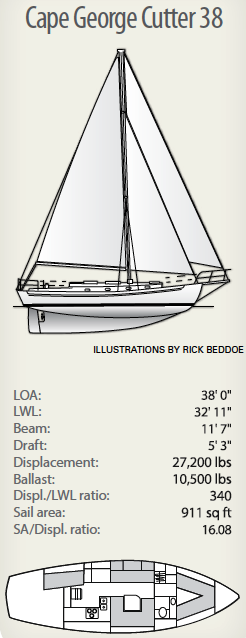

Styled by builder Cecil Lang after William Atkin’s classic Tally Ho Major, the Cape George 38 is a traditional cutter with a counter transom, fairly flat sheer, and nicely cambered coachroof.

With a seven-year circumnaviation already under his belt by the time he was 20, Dave Boots was looking to build the perfect cruising boat for himself and his wife, Melanie. The newlyweds paid a lot of money to a famous Canadian sailboat designer for a custom design built in aluminum — similar to the boat Dave’s family sailed around the world. Dave planned to go to school to learn to weld aluminum so he could build the boat. But then the price of aluminum went out of sight in the mid-1980s, and the couple looked for other options.

A friend showed them a boat he was building from a fiberglass hull. It was built by the Cecil Lang and Son boatyard in Port Townsend, Washington. The traditional full-keel boat appealed to Dave and Melanie and they ordered a hull. It took them thousands of hours over 14 years, but in 2000 they launched their beautiful Telerra, a Cape George 38.

Company History

In 1974, New Zealander Cecil Lang started a boatyard on Cape George Road outside of Port Townsend. His goal was to build a strong cruising boat modeled after William Atkin’s 34-foot Tally Ho Major. Lang enlisted the help of Seattle boat designer Ed Monk to adapt the design for fiberglass construction. That first design became the Cape George 36. Over the years Lang developed 31-, 34-, 38-, 40.5-, and 45- foot versions of the design. All are burdensome full-keelers with no cutaway forefoot, short overhangs, a cutter rig, and strong family resemblance.

Lang built the hulls out of hand-laid fiberglass, but the rest of the boat — decks, bulkheads, and interiors — was wood. Lang built each boat on a custom basis and sold the boats at any stage of completion. Many of the buyers bought only the hull and finished it themselves.

In 2000, Lang retired and the yard was largely fallow. Four years later, Todd Uecker, who worked for Lang in the 1990s, and his brother Tim bought the yard and reopened it as Cape George Marine Works. He continues to offer customers anything from a bare hull to a completed vessel.

Design and Designer

William Atkin and his son, John, created more than 300 small-boat designs during the mid-1900s. Most of them were featured in their monthly column in Motor Boating magazine. Their designs fueled the dreams of many armchair sailors and resulted in some iconic cruising boats.

A few enterprising boatbuilders adapted popular Atkin designs to fiberglass construction in the late 1960s and ’70s. Many of these were double- ended cruising boats, a development of Colin Archer designs. Bill Crealock designed the Westsail 32 based on two Atkin 32-footers, Thistle and Eric. The Westsail started a revolution in the early 1970s, helping to popularize offshore cruising. Another Atkin heart- throb, the Ingrid 38, spawned fiberglass versions from at least four builders: the Alajuela 38, the Blue Water Ingrid 38, Orca 38, and Bently 38.

Lang chose Atkin’s Tally Ho Major as his design ideal. It was a scaled-up version of Atkin’s original Tally Ho, being about 4 feet longer. Of the Major, Atkin said: “The lines show an easily driven hull … a wholesome underwater profile with reasonable forefoot depth, slight tumblehome to the topsides, and a rather straight sheer … The bow and stern overhangs balance and, of course, the rudder is hung on the transom, which is the proper location for it, and the most scientific.”

When Monk modified the design for fiberglass construction, the cutter grew another 2 feet to 36 and the beam grew 8 inches to 10 feet 6 inches. And, because the fiberglass hull was thinner, the interior volume got a boost.

By the time Dave and Melanie visited Lang’s yard in 1986, the new Cape George 38 was available. “The extra 2 feet of length, additional beam, and more tumblehome makes a huge difference in interior volume between the 36 and the 38,” Dave says. The 38 also features a rudder that is not hung on the transom, which allowed Dave to have the wheel steering he wanted. Even with the changes, there is no mistaking the 38’s lineage.

Construction Details

Cape George hulls are hand-laid fiberglass with vinylester- and polyester-based resins, biaxial glass fabrics, rovings, and mat. Nominal hull thickness is ½ inch at the bulwarks increasing to 1 inch at the keel. A beamshelf of laminated Douglas fir is integrally bonded and glassed to the hull as a foundation for the deck beams.

Dave and Melanie welcomed hull #6 to a 50-foot-long, fully enclosed boatshed. They built it in front of the cabinet shop Dave used for his business as a general contractor next to their house on land they had cleared themselves. Once the hull was inside, they finished building the end wall of the shed. That’s where the boat stayed for 14 years.

Dave cast his own lead ballast. It is 10,000 pounds, about a quarter of that from used tire weights he collected from local tire shops.

He built integral water and fuel tanks above the ballast and in the bilge below the cabin sole to save space and keep the weight low. Every foot or so he glassed in baffles, and each of the compartments has its own bronze inspection port for cleaning. Telerra has 160 gallons of fuel tankage and 160 gallons of water tankage, not counting the 17-gallon freshwater tank for flushing the head. It also has a 40-gallon blackwater tank.

While the hull was still pretty bare, Dave bonded 100 square feet of copper mesh to the inside of the hull to serve as a counterpoise for his shortwave radio. He credits this for the great reception on his Icom 802. “It just booms,” he says.

He then installed ½-inch surfboard foam on the inside of the hull for insulation before installing the bulkheads and a ceiling made from Port Orford cedar.

By far the biggest job was building the deck, cabintop, and cockpit. None of the Cape George models has molds for the boats’ “lids”; they are all made from wood. Many of the trunk cabins are square, flat-sided affairs. Some even split the deckhouse at the mast, giving the boats an old-fashioned look.

Dave wanted curved cabin sides, so he built a bending jig 20 feet long on which he laminated five layers of ¼-inch plywood. He used about 5 tons of lead bricks to clamp the lamination. The result is a beautiful sweeping curve that parallels the curve of the boat’s bulwarks. It worked so well that the bending jig is now employed by Cape George Marine Works for the boats they build.

Dave laminated the deck beams from Port Orford cedar with the under- side lamination of mahogany to match the rest of the interior wood. Before attaching the cabintop he carefully taped off where the inside would attach to the deck beams and painted several coats of white paint in between. The contrast between the white paint and bright-finished deck beams is still beautiful 19 years later and gives the interior a traditional feel.

On the outside, Dave covered the decks in fiberglass and multiple coats of gelcoat, which he then sanded smooth before applying two finish coats. The result is a smooth professional finish that looks like a molded fiberglass deck.

Interior

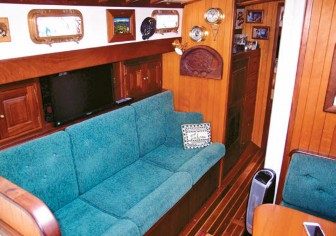

The bridge deck and small companionway necessitates a five-step ladder to enter the boat. To starboard is a large, stand-up chart table with an impressive array of mahogany drawers below it. In port it serves as additional countertop space for the port-side galley, which features a gimballed electric stove and a large top-loading refrigerator and freezer. “When I can’t reach the bottom of the freezer, it will be time for us to move off the boat,” Melanie quips.

Forward of the galley is a 7-foot settee that converts to upper and lower bunks with leecloths that make excellent sea berths. On the starboard side is a large U-shaped dinette. Forward of the dinette is the door to the head, which has a separate shower. Opposite the shower is a hanging locker and storage. The bow is home to a cozy V-berth and the anchor chain locker.

The layout is well thought out and should be comfortable both in port and at sea. Two large hatches and several bronze portlights provide plenty of light and ventilation. The Port Orford cedar and mahogany keep the interior subdued, even with the white Formica countertops and white paint on the overhead and cabin sides. Dave’s skill as a cabinetmaker is evident in all the beautiful drawers and raised-panel doors throughout the boat. He chose 6 feet 2 inches as the headroom under the deck beams, which is plenty for him and his wife. Other Cape George Cutters have more or less headroom, depending on the builder.

Mechanical

The elegant and simple cabin layout belies Telerra’s complex mechanical systems under the cockpit. Behind the companionway ladder are two large, raised-panel doors. They open to give full access to a 76-horsepower Mercedes 240 marinized diesel. It’s the same size as many Mercedes diesels in cars, but based on the commercial block. Dave paid $4,000 for the new engine from another boatbuilder whose dreams — and marriage — didn’t work out.

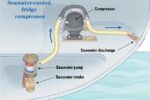

To starboard of the engine is a 4.5-kW, 35-amp Entec diesel generator. The clean and well-organized engine room is also home to a 15-gallon-per- hour watermaker, a 1,000 amp-hour battery bank, a 2,500-watt inverter, and a Wabasco diesel heater. The heater not only heats the cabin, but also the lockers, including the chain locker, and provides domestic hot water. When the boat’s main engine is running, the waste heat from the engine provides heat for the system.

As Dave installed all the equipment himself, he made sure that it was accessible and easy to service. At the time he was building Telerra, solar and wind were costly and not reliable. The diesel generator was the best option for an electric stove and oven along with other amenities. When Dave sailed around the world with his family as a teenager he lived with alcohol and kerosene cookers. He knew he didn’t want either of those. He also did not want to have propane aboard. The most livable option, he and Melanie decided, was electric.

“We knew we were going to live aboard for a long time and we wanted to be comfortable,” Melanie says. “We didn’t want to feel like we were camping.”

Rig

Many Cape George cutters have owner-built spruce box masts. Dave said he could have built a wood mast for about $4,000 at the time. Instead, he spent around $20,000 to have a custom aluminum mast built. “I have enough maintenance to do without varnishing a mast every year,” Dave says.

When Dave and Melanie launched Telerra in 2000, SparTec had a six-month wait between order and delivery. Eager to use Telerra, they didn’t wait for a mast and motor-cruised the San Juan Islands shortly after launch.

Now, a shiny grey, keel-stepped mast with double spreaders supports their cutter rig. The standing rigging is 3⁄8-inch stainless steel wire with Norseman fittings. Both the jib and staysail have roller furlers. A custom aluminum bridge spans the storm hood supporting the track for the mainsheet traveler.

Deck

Spacious sidedecks, substantial bulwarks, and extra-high double lifelines make moving around on deck feel secure. Dave had his lifeline stanchions made of 1¼-inch stainless steel tubing and through-bolted them to the bulwarks. He needed the extra strength because the lifelines are a full 37 inches above the deck. Telerra’s other hardware feels solid and oversized. The electric windlass, for instance, looks like it would be at home on a 50-footer. “I pulled up about a million miles of chain by hand while I was sailing around the world with my family,” Dave says. “That was enough.”

Telerra to New Zealand

In 2006, Telerra and her crew left the San Juan Islands and headed south. After stopping at several ports along the Oregon and California coasts, they joined the Baja Haha, a cruising rally that leaves San Diego at the end of October each year for Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. They cruised the Sea of Cortez and south to Zihuatanejo, Mexico. From there they sailed to the Marquesas Islands, a passage of 25 days. There was no rain for the entire passage. “The boats in front of us and behind us that we talked to on the radio all took a beating, but we had a great sail,” Dave says.

They cruised the Society, Cook, Tonga, and Fiji islands and landed in New Zealand where they stayed for one-and-a-half years. (Dave went to school there during his family’s circumnavigation. He also has an older brother who jumped ship and still lives there.) From there they sailed to Samoa and then against the trade winds to Christmas Island and Hawaii and then home to Olympia, Washington — a total of 66 sea days. “It was not scary, just noisy,” Melanie says.

Sailing

Telerra ghosted along well in winds of about 5 knots on the day of our test sail. Her considerable weight kept her going through each tack, her stately pace barely changing. Dave set up running rigging so everything is just where it should be, making trimming and tacking quick and easy. Lazy-jacks and the absence of battens make the mainsail easy to handle. It doesn’t take much imagination to see her sailing like a thoroughbred in big winds and heavy seas.

“The boat balances well in any weather and sails like a dream,” Dave says. “The boat is stiff and quite fast, but takes a bit of wind to get her going. She tacks well and has the right amount of sail.”

During long ocean passages, like the one from Mexico to French Polynesia, Dave usually kept a reef in the mainsail. “We kept it comfortable and aimed for 5 knots,” he says. “We could have pushed it to 6 knots, but I wanted it comfortable for Melanie.”

Things to Look Out For

When the boat mover came to Dave and Melanie’s home to take Telerra to her launch site, he told Dave, “You are one in a thousand; most of my moves are from one boat shed to another.” Therein lies the tale: many boats sold as bare hulls do not get finished, at least not by the original owner. And some that do are not finished well, certainly not to the high level Dave and Melanie insisted upon. Their skills and commitment are too often the exception instead of the rule.

One of Lang’s concerns about boats built from his hulls was that homebuilders sometimes scrimped and did not put enough lead ballast in their boats. Another concern for Cape George cutters, even the professionally built ones, is rot, particularly on the inside of the bulwarks. Dave didn’t want this to happen to his boat, so he laminated the inside of the bulwarks with 2 inches of solid fiberglass.

Conclusion

Atkin’s original Tally Ho Major is a yachting masterpiece. Lang (with Monk’s help) only improved an already great boat. The siblings spawned from the original Cape George 36 remain true to the vision of strong, seaworthy, and seakindly boats. If you are looking for a traditional passagemaker, you can’t do much better than a Cape George Cutter. If you are lucky, you will find one as well-built as Telerra.

Brandon Ford, a former reporter, editor, and public information officer, and his wife, Virginia, recently returned from a two-year cruise to California, Mexico, and seven of the eight main Hawaiian Islands. Before their cruise they spent three years refitting their 1971 Columbia 43, Oceanus. Lifelong sailors, they continue to live aboard Oceanus and cruise the Salish Sea from their home base in Olympia, Washington.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com