Tringa side-tied near a bridge passing over the New York State Canal System in Seneca Falls.

A first cruise after downsizing

Issue 128: Sept/Oct 2019

Like many baby boomers, my husband, Chris, and I aren’t quite as quick, strong, and nimble as we once were. Increasingly attracted to the advantages of a boat with smaller sails, lighter ground tackle, and lesser draft, we sold our 32-foot sloop, Titania, a 1968 Chris Craft Cherokee, and bought a trailer-sailer, a shoal-draft 3,000- pound Compac 23 called Tringa. We like having a boat we can push around when leaving the dock and a mast we can step ourselves. Tringa doesn’t sport a 7-foot bowsprit that we have to negotiate when time to reduce the headsail, and we can keep her at home on a trailer during the off-season, where she’s easy to work on. She’s a relatively new boat by our standards, having been built in 1985, and came equipped with a relatively new motor and trailer. In sharp contrast to our last boat purchase (“That Sinking Feeling,” July 2015), she was ready to go.

We were intrigued by the notion of traveling overland at 60 miles per hour with our new boat, a gateway to distant waters and new horizons. We envisioned winter vacations spent exploring Florida’s shallow waters, or perhaps a three- week trip west to the greatest Great Lake, Superior.

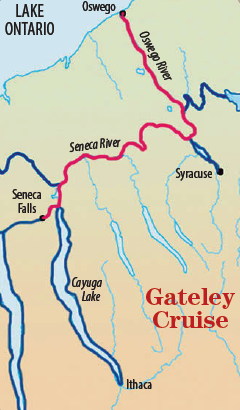

We decided our first cruise aboard Tringa would be to Ithaca, home to Cornell University and Ithaca College. It’s famous for its museums, culture, and natural beauty, but it’s also where Titania’s new owner berthed her, and visiting our old boat on our new boat sounded like a plan. Furthermore, we wouldn’t need to tow Tringa because from our home it was just 10 miles by water to Oswego, where the Oswego River connected Lake Ontario to the Seneca River (both part of the 525-mile New York State Canal System) which connected to the north end of 38-mile-long Cayuga Lake, at the southern end of which was Ithaca. We started packing.

Our first surprise was how roomy the 23-foot pocket cruiser is. I crammed the pressure cooker, a sizeable cast-iron skillet, and an amazing amount of dry and canned goods into her various spaces and lockers, and we stuffed her forepeak with bedding, more food, mast-lifting gear, and our minimal cruising wardrobe. Tringa settled on her lines, but there was still room to stretch out on the two main cabin berths. A big factor accounting for the Compac’s interior space is her lack of an inboard engine and the associated shaft, exhaust system, and fuel tank. Instead, we used the space under the cockpit to stow a large cooler, wastebasket, toolbox, and a half-dozen 1-gallon water jugs. An outboard motor (hung on a transom bracket) provided all the non-wind propulsion we needed.

Our first surprise was how roomy the 23-foot pocket cruiser is. I crammed the pressure cooker, a sizeable cast-iron skillet, and an amazing amount of dry and canned goods into her various spaces and lockers, and we stuffed her forepeak with bedding, more food, mast-lifting gear, and our minimal cruising wardrobe. Tringa settled on her lines, but there was still room to stretch out on the two main cabin berths. A big factor accounting for the Compac’s interior space is her lack of an inboard engine and the associated shaft, exhaust system, and fuel tank. Instead, we used the space under the cockpit to stow a large cooler, wastebasket, toolbox, and a half-dozen 1-gallon water jugs. An outboard motor (hung on a transom bracket) provided all the non-wind propulsion we needed.

We set sail with a light wind and arrived at Oswego in time to take the mast down and make our way through the first three locks. Canal travel on the New York State system is strictly a motoring affair, thanks to the many low bridges that traverse the waterway. Using the pivoting A-frame system and a rope come-along for controlling descent of the deck-stepped mast, we dropped the spar and secured the rig upon arrival in the Oswego River. We were surprised that this unstepping took us a couple hours. If it took two hours each way to down-rig, and then the same to raise and re-rig, was it worth it for a day’s sail? We decided it wasn’t and left the rig down, shifting our cruise destination from Ithaca to Seneca Falls. Perhaps someday we’ll drive down to visit our old boat in Ithaca.

We were pleased with the prospect of spending more time on the New York State Canal System, a National Historic Landmark. We had previously traveled the eastern part of the Canal System during a trip to the coast, so we had some idea what to expect.

Susan and Chris approach one of the locks on the Oswego Canal, which connects Lake Ontario to the New York State Canal System. To the right of the lock, water spills over the length of the damn.

Opened in 1918, the system is composed of the Erie Canal, the Oswego Canal, the Cayuga-Seneca Canal, and the Champlain Canal. While each of these canals existed prior to 1918, the New York State Canal System (formerly known as the New York State Barge Canal) was an upgrade to all the existing canals. While some of the original canal routes were preserved, much was new, and all of it was dredged to a minimum of 12 feet deep and widened to at least 120 feet wide. Modernization of the canals ceased in 1970, as commercial goods transport had largely moved to land transport. Today, there is very little commercial use of the canal system and the 57 locks are maintained strictly for private recreational vessels and flood control.

Susan waits on the foredeck next to a lock wall as the water level rises, slowly lifting Tringa and crew.

The creak, groan, and heavy thud of the lock doors and the descent into the clammy cool depths of the slime-covered lock chamber revived memories of our 1999 canal crawl, though little Tringa was far easier to manage in and out of the locks than her 9,000-pound predecessor. We found the waterway lightly traveled. As we followed the winding course of the Seneca River through the early summer landscape, we rarely shared a lock with another boat.

Seneca Falls was once the, “pump center of the world.” Today, 150-year-old Gould’s Pumps remains and is one of the area’s largest employers. “Working Man’s Alchemy” is a sculpture along a walking/biking trail and is dedicated to Gould’s and the town’s history.

The legendary Canal that helped build a nation and change history is now largely bypassed by modern society. With its 100-year-old machinery and early-twentieth-century tugs and work boats, it’s a living history museum. As we passed through the countryside, we caught glimpses of old stone ruins of former canal locks along the shore and passed abandoned aqueducts and bridge supports from former days of canaling. In several towns, abandoned brick factories stood along the water, their windows shattered and their walls crumbling. We often traveled for miles without seeing any sign of current human habitation. In 1850, this canal was the interstate highway and 200 boats a day passed through the busier locks. Today, the pace of life on the canals is slow and the calm waters reflect the passing countryside. Along the banks, we caught glimpses of deer, fox, muskrats, fishing herons, soaring ospreys, and a mink that scampered lightly over the dead limbs of a fallen tree. We locked through several times with mother mallards and their ducklings in tow.

Tringa tied up along the free city dock in Seneca Falls, New York. A selection of restaurants and a laundromat were an easy walk away.

The canal system is about predictability. In pre-fossil-fuel days of sail, canal travel and trade could be done on a schedule, as horse- or mule-drawn barges traveled long distances at a known rate. As a result, towns prospered. Cities like Buffalo and Rochester arose, and Clinton’s Ditch made New York the Empire State.

In the mid-1800’s, Seneca Falls was a hotbed of the suffrage movement. This old knitting mill along the city’s waterfront is being remodeled to serve as a women’s rights museum.

The canal also brought a flow of fresh ideas that fueled new notions and social movements across the pre-Civil War countryside. This trade helped fuel a burst of technological development and a surge in progressive politics that fostered abolitionist and women’s rights movements, as well as a host of radical and downright odd Utopian and spiritual endeavors and communities. We learned much of the region’s history at Seneca Falls, home to several museums on technology and women’s rights.

One unknown when we cast off was our motor and its fuel consumption. Our 4-cycle 6-horsepower Mercury/Tohatsu hummed along day after day and we were pleasantly surprised at the thrifty fuel economy. Our modest 3-gallon fuel tank allowed for about a 60-mile range. With an additional 2-gallon jerry jug and the motor’s integral tank capacity, we refueled only twice during our four-day trip. The disparity of waterfront real estate we passed — everything from liveaboard boats and shacks to 5,000-square-foot McMansions — was a constant source of interest. On occasion, we passed a sailboat returning from saltwater or a trawler doing The Loop.

Tringa under sail near her homeport, Little Sodus Bay, New York, on Lake Ontario.

After experiencing a slice of upstate New York’s history and landscape to the gentle hum of our outboard, it was a pleasure, upon our return to Oswego, to raise the mast and transform back into a sailboat. And after having been constrained on a nautical highway, it was oddly exciting to look north at the watery horizon, and to contemplate our own.

The Waste Factor

Cruising aboard such a small boat, without a dedicated head or holding tank, presents a particular challenge. We considered several options before settling on the Double Doodie waste bags and Bio-Gel powder (an absorbent that deodorizes, gels, and promotes composting). This is a waste-storage system used by leave-no-trace backcountry hikers, and it’s nothing more than a heavy-duty zip-lock garbage bag reinforced with a second layer of plastic and sized to fit the standard 5-gallon bucket (with the powder added).

Bio-Gel-powder effectively turns biological waste materials from humans or animals into a gel that is safe for “direct and indirect contact.” Bio-Gel-treated waste packaged in bags like this is approved for landfill disposal and we were thus able to toss them in canal-side trash receptacles. This made our trip convenient (and possible), but the idea that we were putting perfectly compostable human manure inside two plastic bags with the half-life of plutonium offended my gardener’s aesthetic. I’ll note too that we did not have an odor problem with this system and that we also endeavored to keep urine out of the bags. For pee only, we used a 2-gallon jerry jug purchased just for this purpose. We emptied this at convenient canal rest stops.

Surprisingly, we didn’t use as many bags as forecast, as we found more waterfront restrooms than we imagined. We found facilities for boaters complete with showers, laundromat, lounge, free 48-hour docking, and flush toilets. Marinas, village lunch counters, and a canal-side restaurant also provided relief.

Despite the success of this system, we’ve not left the drawing board. Composting is still our preference and although we could not figure out a way to fit a full-scale composting toilet aboard our little boat, we’re now looking at something called C-Head, a more compact version of the composting toilets we have seen aboard other boats.

Compac 23

The Compac 23 is one of several cruising sailboats that range from 23 to 27 feet built by the Hutchins Company, Inc. of Clearwater, Florida. She’s built for comfort and practicality rather than speed, and various versions have been in production since 1979. We were attracted by the comfort of the cockpit and owner-added bimini, as well as by the quality of the boat’s hardware that included six opening ports, many lockers, ample storage areas, and the generous use of solid wood and teak veneers below. We liked the practical anchor roller, rode locker, and short bowsprit for ground tackle. Several other trailer-sailers we looked at had little or no provision for stowing and setting anchors.

Lake Ontario sailor and author Susan P. Gateley published Saving The Beautiful Lake, A Quest For Hope, that centers around a cruise aboard her 1950s-built 47-foot schooner, Sara B. Her latest book is an historic novel, Widow Maker. Visit susanpgateley.com for more information.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com