World-girdling pioneers inspired generations of sailors with their writing

Issue 121: July/Aug 2018

I want to tell a story about Bernard Moitessier. It is not the famous one about him crossing his outbound track while seemingly well placed to win the 1968 Golden Globe Race around the world, only to abandon his claim on the $85,000 cash prize (today’s dollars) and tack away eastward for Tahiti, 12,000 miles distant. This one happened years earlier.

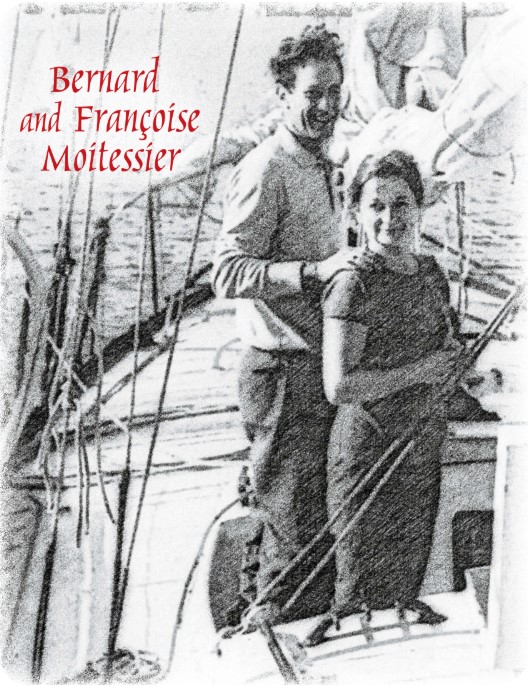

At the time of this story, Moitessier has been bluewater sailing for a dozen years. He and his wife, Françoise, have been cruising Joshua, their 39-foot ketch, through the Mediterranean, the Caribbean, and the tropical South Pacific for more than two years. It is germane that Joshua is named for Joshua Slocum.

In Cape Horn: The Logical Route, Moitessier tells how, rather than continuing west, he and Françoise have plotted their return to France the shorter way, east around Cape Horn. On December 14, 1965, they are deep in the Roaring Forties. Gales are frequent and vicious, but on this day the wind has found a higher register and is pushing the towering waves to unstable heights.

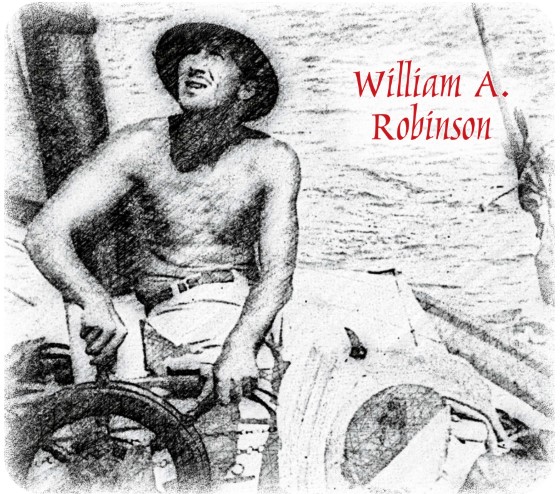

Moitessier has read Miles Smeeton’s account of his two disastrous attempts at rounding Cape Horn. William A. Robinson had been aboard Joshua in Tahiti, telling Moitessier of his own experiences in the high southern latitudes. Heeding their combined counsel, Bernard has his foot on Joshua’s brakes, dragging five weighted warps astern to slow the boat. However, this tactic limits maneuverability and the drogues lose their effect as following waves overtake. Inevitably, in a moment of inattention, Joshua yaws, then broaches, rolling enough to put the masts in the water. With renewed vigilance, Bernard steers the boat exactly stern on, only to have Joshua surf down the face of a particularly steep comber and bury the bow to the mast. Aware that an end-over-end disaster is but a single wave away, Bernard considers abandoning this route home in favor of a return through Panama. Meanwhile, Joshua has to survive the blow.

Moitessier’s emotion at this critical moment is more disappointment than fear. He has also read the account of Vito Dumas sailing around the globe south of the three great capes two decades earlier. Was big steel Joshua less capable than Dumas’ wooden 31-footer? That made little sense to Bernard. He asked Françoise to search through their small ship’s considerable library for the account of Dumas’ voyage. Dumas claimed to have carried some sail always, surfing down overtaking waves at a shallow angle to avoid both pitchpole and broach. Turning slightly off the waves, Bernard watched as Joshua heeled and planed on her leeward bow. With each subsequent wave, Moitessier became more convinced that this was the better tactic for the buoyant Joshua. Picking his moment, he dashed aft with a razor-sharp Opinel knife and severed all the trailing lines. In that instant, Joshua became a different boat. A hundred days later, and halfway around the world, boat and crew safely sailed back into the Mediterranean.

I am fond of this story because it brings together at a single moment, in one of the most remote spots on the globe, Joshua Slocum, William A. Robinson, Vito Dumas, Miles and Beryl Smeeton, and Bernard Moitessier. I tell it here just to ask a single question: Are these legendary sailors familiar to you?

With this issue, Good Old Boat magazine celebrates two decades of delivering sound and relatable guidance for choosing, maintaining, and improving venerable sailboats, many constructed 30, 40, even 50 years ago. This admirable milestone offers the perfect moment to ponder continuity in our community.

The inspired design and solid construction that give our old boats both value and longevity trace directly back to the handful of sailors in my story. Not to just them, but these sailors are representative of an era and culture that, from the early days of fiberglass boat construction, gave birth to the abundance of cheap, strong, seaworthy, seakindly, and timelessly graceful sailboats that would be capable of undertaking a similar adventure.

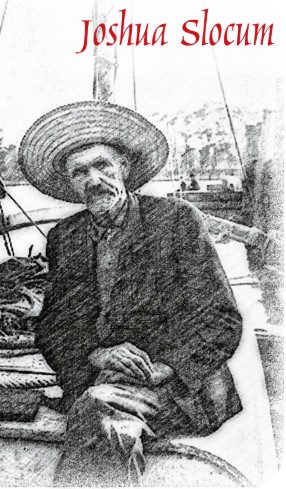

“I had resolved on a voyage around the world, and as the wind on the morning of April 24, 1895, was fair, at noon I weighed anchor, set sail, and filled away from Boston, where the Spray had been moored snugly all winter.” With this matter-of-fact sentence, Joshua Slocum describes the beginning of a revolutionary new possibility, that of sailing a small boat around the world with neither crew nor extraordinary expense. It would be three years before he returned to New England, having indeed circled the globe. Slocum’s account of his voyage, Sailing Alone Around the World, was initially published in 1900. It remains in print today, 118 years later.

Sailing Alone Around the World was a revelation, igniting the imaginations of the next generation of sailors. One of those was another Yankee, William A. Robinson. As a boy he sailed a 15-foot canoe on Lake Michigan, but dreamed of the possibility Slocum had shown. By age 26, Robinson had acquired a 32-foot Alden ketch that he named Svaap—“dream” in Sanskrit. He entered Svaap in the 1928 New York to Bermuda race, with a private plan to sail beyond. In fact, Robinson would sail on to some of the most exotic ports in the world, transit both the Panama and Suez Canals, and not return home until the very end of 1931. Like Slocum, Robinson would write a book about his voyage, Deep Water and Shoal, first published in 1932. To this day there may not be a more interesting and entertaining sailing book. (Robinson is more famous for his 1936 book, Voyage to Galapagos, in which he tells of the ruptured appendix that left him three days from near-certain death. The good fortune and heroic efforts that saved his life are both miraculous and a tribute to the best in humanity.)

Slocum’s voyage had taken him through the Strait of Magellan, so his story was well known to Argentine sailors. One of those was Vito Dumas, who in 1933 commissioned a 31-foot Colin Archer-inspired ketch to follow in Slocum’s wake. But life interfered with Dumas’ plans. He sold the boat but kept the dream. In 1942, with war raging literally around the world, Dumas bought his boat back and embarked on an east-about circumnavigation beneath the three great southern capes. It was Dumas’ account of his experience that Moitessier drew upon to rescue his own high-latitude voyage. My personal takeaway from reading Dumas is far more modest: after a particularly difficult passage, he declared, “I will never, never sail again!” It was a sentiment I was all too familiar with, so hearing it from someone of Dumas’ stature was reassuring. Of course, Dumas wasn’t finished with sailing. A month later, he was at sea again and would continue to make significant passages for most of the remainder of his life.

Miles and Beryl Smeeton had never sailed before when, at ages 44 and 45, they encountered Tzu Hang for sale in England. I do not know if they had read Slocum, but the year was 1950 and the possibility Slocum spawned had by now become the norm for sailing yachts. A good design could take you anywhere. They bought the boat and sailed her across the Atlantic, through the Panama Canal, and up the North American west coast to their home in British Columbia, learning to be sailors on the trip. Soon enough, they went back aboard, sailing to Australia. Attracted by the mountain-climber’s mantra, “Because it’s there,” they left Melbourne in December of 1956 to sail around Cape Horn and back to England. Nearing the Horn, Tzu Hang was pitchpoled and severely damaged. They nursed the crippled boat to Chile, made repairs, then set off again almost a year later. In the same waters, Tzu Hang was capsized for a second time. The book Miles would write after limping back to Chile and shipping the yacht to England would be perfectly titled Once Is Enough. Smeeton’s voice epitomizes the British slogan to “keep calm and carry on.”

This brings us back to Bernard Moitessier, whose early sailing was less stellar than his early writing. His first book, Sailing to the Reefs, was about his vagabond existence aboard his first two boats, which both come to grief on reefs, but it was written with such honesty and humor that it still found an appreciative French audience. It also funded the construction of Joshua. Later, Moitessier would write such compelling books about his larger-than-life exploits in Joshua that he would become a celebrity and his books would launch a veritable fleet of French sailors sailing to distant ports. The takeaway here is that Moitessier was voyaging because of Slocum, sailing for Cape Horn because of the Smeetons, prepared because of Robinson, and successful because of Dumas. Take any one out of the equation and the outcome of my story is different, Moitessier does not write more books, and the path of every sailor who points to Moitessier as his or her inspiration is altered.

In the UK at this time, and in other English-speaking countries, Eric and Susan Hiscock, Francis Chichester, Edward Allcard, and others were providing this inspiration. In the US, it was Sterling Hayden, Robin Graham, Hal and Margaret Roth, and Lin and Larry Pardey, to name just a few.

Forty years ago, at least name familiarity with these sailors was unavoidable, as every major boating magazine included in nearly every issue a Book-of-the-Month cardstock insert featuring full-color images of the books written by them and others. Publishers were also sending out truckloads of targeted direct mail. The result of such promotion and ready availability was robust book sales and wide readership. But by the time the first issue of Good Old Boat went to print, the distribution channels for sailing books had all but disappeared. Even the best-known titles often could be found only in a big-city library or perhaps a used-book store. The predictable consequence was that these sailors faded from our shared consciousness. The link between the current generation of sailors and those who inspired the boats we so revere was broken.

If this describes you, there is good news. After a two-decade hiatus, most of these classic accounts are again readily available. Of the sailors named in my story, only Vito Dumas is not available on Amazon Kindle. Amazon also provides easy access to used-book sellers around the world, where you will find books by literally all the other sailors already mentioned, plus John “Venturesome” Voss, Richard Maury, John Guzzwell, Alain Gerbault, Ann Davison, H.W. Tilman, and a host of others. Even Good Old Boat listed Slocum and Guzzwell among its audiobook offerings.

Like our old boats, these old sailors offer value undiminished by years. There is much to be gained reading their stories and, for the sailing community at large, in sharing them. Aside from being thoroughly entertained, you are likely to learn a great deal about sailing, about sailboats, about the world, perhaps even about yourself. And maybe, at some critical moment, the words of one of these sailors will save your bacon.

Don Casey’s This Old Boat has been the reigning go-to guide for sailboat maintenance and upgrade for two generations of sailors. A friend of Good Old Boat from the first issue, he gave his approval for the magazine’s title.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com