The visually impaired rely on their other senses to keep them on course

Issue 122: Sept/Oct 2018

We sailors often say that much more than sight is involved in sailing, that feeling is just as important as seeing — we feel the direction and intensity of the wind or the heel of the boat more than we see them. But would we really be able to sail comfortably and confidently if we were blind? Can we even imagine it?

I have been sailing — cruising as well as racing and teaching — for more than 20 years, but only two years ago discovered the world of blind sailing. Having recently moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, I was looking for sailing opportunities and stumbled upon a chance to instruct people who are blind and want to sail. That opened a whole new world to me, a world that has continued to expand and deliver wonderful and enriching experiences.

Despite my expertise as a sailor, I was quite nervous the first time I went out as a sailing instructor on a J/24 with two people who were visually impaired, and I was very grateful to have had the support of another sighted instructor on board. However, my tension dissolved almost as soon as we set sail and I saw the incredible sensitivity of our two students to wind, heel angle, sounds, and other non-visual inputs. They were a sweet recently engaged couple who had sailed only once before. Their enthusiasm, delight, and readiness to learn were contagious. They eagerly took turns steering the boat and trimming the mainsail. The only interventions we two sighted instructors made, for safety reasons, were jib trimming, course directions, and docking.

As we sailed around the area of San Francisco Bay behind Treasure Island, we instructors painted the scene around us in words for our visually impaired students. While they steered and trimmed, we offered only the minimum input necessary and answered their questions. For example, I might offer the student at the helm guidance on how much to move the tiller to point the boat more into the wind or to bear away. I might tell the student trimmer how much sheet to ease to trim the mainsail. Normal practice in this kind of instruction is to use a numeric scale to give the students relative quantitative information, such as 1 up, 2 up, 3 up, for the helmsman to point the boat more into the wind, or 1 down, 2 down, 3 down, to bear away.

This first experience really opened my eyes and made me want to engage more with the world of blind sailing. As I continued volunteering with Blind Sail SF Bay, and got involved with the Bay Area Association of Disabled Sailors (BAADS), I discovered something astonishing: organizations in the Bay Area and other locations in North America and around the world hold fleet and match-racing regattas for sailors who are blind!

A fleet regatta involves several boats with crews of four, two of whom are sighted and two of whom are blind. The sighted crew oversee the jib, foredeck, and tactics (the tactician is not allowed to touch any of the sail controls), while the blind members of the crew work the helm and mainsail trim from the cockpit.

In the blind match race, on the other hand, all the sailors are visually impaired and the course is set around buoys that emit sounds. The sailors use those sounds to judge their range and bearing from the buoys, and judge where the competing boat is using the audible tack indicators fitted on each boat. Other than the use of the audible equipment, the boats and rules of blind match racing are identical to those used by sighted crews.

Incredible as this might seem, the most amazing aspect of this feat is the way blind sailors process the information they receive from their environment. I learned a lot about their techniques from Walt Raineri, director of blind sailing at BAADS. Raineri says he attempts to internalize a visual image to keep the course and the other boats he places on a mental map. He adds that it’s even more important to “understand the algorithm to employ in a given situation so that I can react, in real time, to changing circumstances.”

Raineri started to go blind in his mid-40s, 12 years ago, because of a hereditary disease, and lost 95 percent of his vision within five months. Remarkably, before going blind he had never sailed. He started sailing as a way to “keep the walls from caving in,” his description of the feeling he experienced after losing his sight.

Going blind as an adult required many adaptations, several of them practical but many of them psychological. And sailing, for Raineri, was one of the keys to his successful adaptation to his new condition.

Raineri sees life in general as a series of steps that each person accomplishes on a daily basis, and sailing is just a very special task in which we have to apply a series of steps to get things done. Acknowledging that blind sailors cannot see objects that might be hazards, such as a floating log or another boat, the acts of sailing and sailboat racing can be successfully accomplished by the application of algorithms, using the auditory information (sound buoys, waves slapping the keel, wind blowing) as well as tactile data (points of contact of the body on the boat, the wind on the face, neck, and ears, the heeling of the boat, and the feel of the helm).

I had the opportunity to witness this algorithmic approach the couple of times I went sailing with Raineri and I was his eyes. Once, practicing a man-overboard drill, he was at the helm, listening to my constant feedback and directions as to where the “person” was in the water with respect to the boat. But Raineri was also listening to various other sounds. He was feeling the wind on his face and the degree of heel with his body.

Personal drive, sharper awareness, a methodological approach, and keen sensitivity are traits I have witnessed in other visually impaired people with whom I have sailed.

Taking it offshore

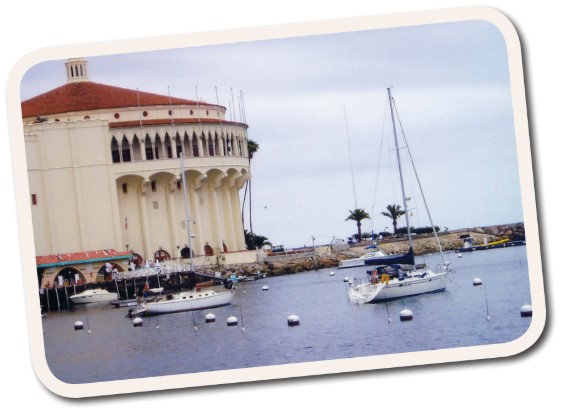

One recent summer, I had the opportunity to be the lead instructor and skipper for one of two boats making an excursion organized by the non-profit organization Peace of Adventure. I was in charge of a Dufour 375 that I and a small crew of sighted volunteers sailed from Los Angeles to Catalina Island with a half-dozen women aboard, all either disabled veterans or visually impaired. The five-day excursion included not just lots of sailing and classroom instruction but camping and hiking on the island. Once again, I had the responsibility to teach people with a variety of sailing skills and disabilities how to sail, but I also had the opportunity to learn from them.

When they took turns at the helm or trimming the sails, I saw the ease with which these disabled (mostly blind) participants, many of whom hadn’t been on the water before, oriented themselves on the boat, the quickness with which they learned the workings of the various parts and mechanisms, and the keen sensitivity with which they maneuvered the sailboat. It was really eye-opening. I intervened only when asked for help or directions; otherwise I spent my time describing to them the surrounding landscape.

I’ll never forget the controlled and serene voice in which Laura, steering as we neared the island and the wind freshened, said to me: “Alec, I’m a little out of my depth, would you mind taking the helm?” So I did, while the other ladies continued sheeting in and out as necessary as we tacked toward the island.

From my wonderful experiences sailing with people who are visually impaired, I know that feeling really is the primary sense necessary on a sailboat.

Resources

Organizations that support blind sailing can be found worldwide:

- Blind Sailing International – www.blindsailinginternational.com

- US Sailing – www.ussailing.org

- Blind Sailing Canada – www.blindsailing.ca

- Bay Area Association of Disabled Sailors – www.baads.org

- Blind Sail SF Bay – www.blindsail.org

Alec Liguori, PhD, has more than 20 years of sailing experience from racing to cruising and from boat deliveries to maintenance and instruction. She is driven by her passion for sailing, science, and education, which has led her to actively coach special sailing seminars for women. She also teaches STEM subjects through sailing and gives talks on the “Physics of Sailing” as a way to reach out to as many and as diverse audiences as possible. Alec currently works as a physics lecturer at San Francisco State University.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com