…and Two More Spunky, Popular Little Big Boats

Issue 132: May/June 2020

Twenty-seven-footers should have a special place in the history of fiberglass yacht design. At 27 feet you could incorporate all the features of a true “yacht” as opposed to a daysailer or weekender—that is, standing headroom, full galley, enclosed head, inboard engine, usually an inboard rudder, wheel steering (standard or optional), and enough accommodations for a small family to take a couple weeks’ vacation, or even embark on longer voyages.

Twenty-seven-footers should have a special place in the history of fiberglass yacht design. At 27 feet you could incorporate all the features of a true “yacht” as opposed to a daysailer or weekender—that is, standing headroom, full galley, enclosed head, inboard engine, usually an inboard rudder, wheel steering (standard or optional), and enough accommodations for a small family to take a couple weeks’ vacation, or even embark on longer voyages.

In retirement, my father-in-law would take his C&C 27 from Lake Ontario to Morehead City, North Carolina, every fall and return in the spring. These boats sold well, and while they weren’t considered entry level, per se, they did entice a lot of families into sailing. Indeed, the C&C 27 stayed in production longer than any other C&C model, going through five iterations and selling more units than any other model. So, it’s more than appropriate to examine three 27-footers from this period.

In his review, Allen mentions that in her day the Watkins 27 was considered a better value than the Catalina 27, so it seemed logical to include the Catalina 27 as one of our comparison boats. It is also worth noting that the Catalina 27, like the C&C 27, stayed in production for many years.

As the third boat I’ve paradoxically picked the John Cherubini-designed Hunter 27, rather than the C&C 27, to introduce another Florida-built boat as well as to include another builder with whom I was once involved.

Though the Hunter 27 also stayed in continuous production for many years, by the time I arrived at Hunter in the early ’90s, the company was no longer building the 27, since the boat was readily available on the used market. Also, it was no longer a profitable boat to build. At less than 30 feet you were lucky to cover your costs, and for larger builders such as C&C, smaller boats were often considered loss leaders, justified only as a way to bring owners into the corporate family and trade up eventually to a larger boat. The tongue-in-cheek philosophy at the time was you would lose money on every unit, but you hoped to make it up in volume. Of course, that never happened.

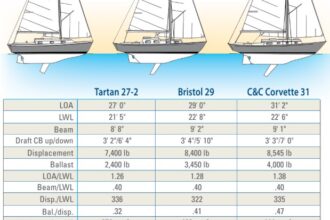

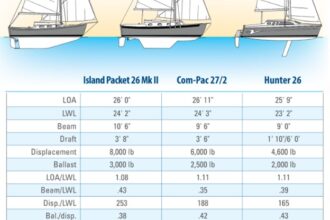

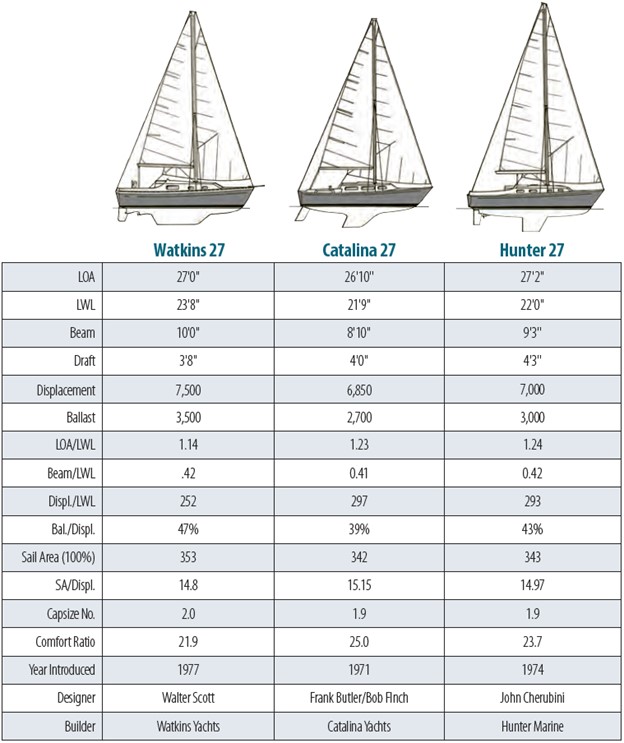

The oldest of these three 27-footers is the 1971 Catalina. She reflects that era of yacht design in her moderately swept keel and rudder. By 1974, the 27 Hunter reflected the influence of the more upright Peterson keel, and the Watkins, launched in 1977, has a more cruising-oriented, longer keel with the slightly shallower draft. The Catalina and the Hunter were obviously aimed at the yacht club racing market, while the Watkins, not so much.

It is also interesting to look at the increase in beam from the older Catalina at 8 feet 10 inches, to the Hunter at 9 feet 3 inches, to the Watkins at a full 10 feet. So, while the keel configuration of the Watkins does not point to a performance heritage, her increased beam, heavier displacement, heavier ballast, and higher ballast/ displacement ratio all indicate a boat that can certainly stand on her feet in a breeze.

The Watkins also has the edge in waterline length, being over 11⁄2 feet longer than the Hunter and close to 2 feet longer than the Catalina. Despite her heavier displacement, that longer waterline results in the lowest displacement/ length waterline ratio of 252 compared to 297 and 293 for the Catalina and the Hunter, respectively.

The Watkins also has the largest sail plan at 353 square feet. However, because of her heavier displacement she also has the lowest sail area/ displacement ratio of 14.8. The Catalina, with a sail area of 342 square feet on the lightest displacement, has the highest sail area/displacement ratio of 15.15, compared to the Hunter with essentially the same sail area, but on a slightly heavier displacement, resulting in a sail area/displacement ratio in the middle at a still-respectable 14.97.

The wider beam, despite the heavier displacement, pushes the Watkins capsize number to 2, while the narrower beams despite lighter displacement result in slightly more conservative 1.9 values for each of the others.

The sail plan configurations are almost identical with all three incorporating masthead single-spreader rigs with double lower shrouds, overlapping 150 percent headsails, and moderately high aspect ratio mains, with only the Hunter approaching anything that could be called “ribbon.”

Performance around a racecourse would very much be a function of wind speed and point of sail. The heavier Watkins with the substantially longer waterline length would certainly have an advantage in higher wind strengths upwind and while reaching at speed. However, the lighter Catali¬na with her higher sail area/ displacement ratio and lower wetted surface might well hold her own in lighter air despite her shorter waterline length.

On the whole, all three are excellent examples of this very popular size range from the 1970s.

Rob Mazza is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. He set out on his career as a naval architect in the late 60s, when he began working for Cuthbertson & Cassian. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com