With three brands on the market, marine composting heads are gaining acceptance.

Issue 132: May/June 2020

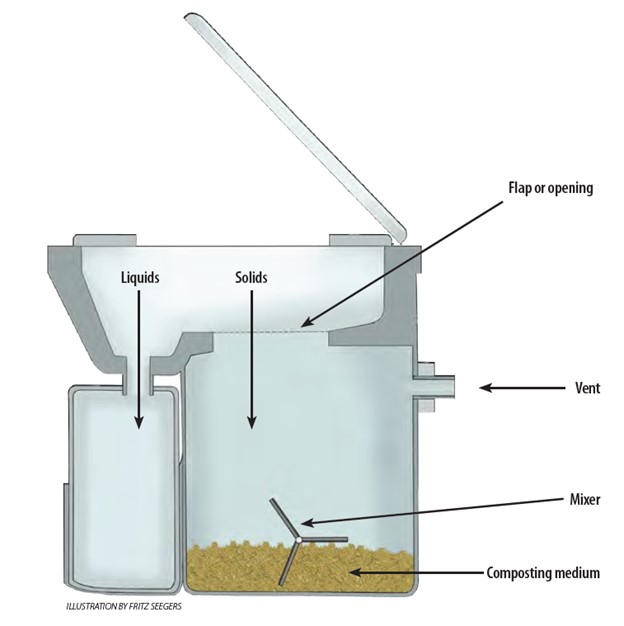

Several marine-suited composting toilets have been on the market for many years, and each has earned a devoted following. All are Coast Guard-approved marine sanitation devices (MSDs) that employ organic materials to compost waste. All are self-contained units with no sanitation hoses, through-hull fittings, or holding tanks. All require the owner to handle human waste to some extent. All separate urine from feces and produce no objectionable odors when managed properly.

Several marine-suited composting toilets have been on the market for many years, and each has earned a devoted following. All are Coast Guard-approved marine sanitation devices (MSDs) that employ organic materials to compost waste. All are self-contained units with no sanitation hoses, through-hull fittings, or holding tanks. All require the owner to handle human waste to some extent. All separate urine from feces and produce no objectionable odors when managed properly.

The three commercially available units are Nature’s Head, Air Head, and C-Head.

The Nature’s Head and Air Head toilets are probably the most common and are somewhat similar in design and operation. Each is approximately 20 inches high, 19 inches wide, and 19 inches deep—about 4 cubic feet in volume (a standard marine toilet is about 2 cubic feet in volume). The Nature’s Head also requires a 2-inch clearance behind the unit for the top to be tipped back to remove the urine tank as well as to unhinge the upper unit from the lower unit.

For both brands, space requirements are often a factor when considering them to replace a conventional marine toilet.

The toilet bowl is designed to direct urine into a jug and feces into a solids tank that contains organic material. Each toilet has a handle on the side that’s used to turn a stirring rod in the solids tank to mix fecal material with the composting medium. Both manufacturers call for forced-air ventilation of the solids tank with a 12-volt fan and hose connected to the outside.

These toilets get good reviews, and those who learn to operate them love them, though they are tall and somewhat bulky with levers, cranks, and brackets on the outside below the seat level.

The C-Head is similar but differs in its form. It is about 40 percent smaller, and a few different models are available. It’s worth noting that C-Head is the only manufacturer that builds models specific to boats. Called the Wedged Back C-Head, it has a cutaway, tapered back to accommodate the curve of the hull against which it may sit. For comparison’s sake, the C-Head is about 2.5 cubic feet in volume. Of course, the downside of this smaller unit is that the liquid and solid reservoirs are smaller, thus requiring more frequent emptying—though these models are a little easier to empty than the other two.

Operation is similar to the Nature’s Head and Air Head, but forced-air ventilation is only required in heavy usage, and rather than a side-mounted handle for stirring, this one has a socket mounted on top into which you insert a handle when the time comes to stir the pot (so to speak). The result is that the C-Head is a “cleaner” design.

All of these units operate similarly, but they differ in how the solids tanks are emptied. For the Nature’s Head and Air Head models, you remove the top of the toilet and set it aside—finding a sanitary way to do this is important—take out the urine receptacle, then detach the base and either carry it elsewhere for disposal or invert it into a garbage bag to dump the contents. For the C-Head, you lift the hinged top—rather than removing it entirely—and remove the collection bucket itself from the base to dump it into a composting area or bag.

For all of these toilets, the medium recommended for the solids tanks is sphagnum peat moss, coconut coir, or sawdust. Peat moss and coconut coir are available inexpensively at garden supply stores and online. The coir comes in compacted brick form that needs to be reconstituted with a little water to create a mulch consistency. You can get sawdust as pine pellet horse stall bedding from supply stores. The pellets must also be reconstituted with a little water to make a very pleasant pine-scented sawdust. Other organic media, such as planer shavings or paper shreds, will also work.

Dumping it

With the use of composting toilets aboard boats increasing, questions arise about proper disposal of collected human waste. What is legal and right?

From the moment human waste is deposited in a composting toilet, pathogens present in the waste begin to die off. But until the waste is fully composted, some level of pathogens remains. And waste from composting toilets is always dumped before complete composting, which can take many months.

Even in toilets in which the liquid waste is separated, the collected urine cannot be (should not be) legally dumped into no-discharge waters. In no-discharge waters, these contain¬ers need to be hauled ashore to be dumped into toilets or other appro¬priate areas. But let’s focus on solid waste, because its disposal is more of a concern for most.

Ideally, organic solid waste collected in these toilets would be deposited into a compost pile where the biological composting process begun in the toilet can continue until completed. Especially for waste created aboard a boat, this is not always realistic. But that doesn’t mean all hope is lost.

Human waste solids may be legally disposed of in municipal solid waste landfills so long as they are contained. In the same way that a soiled disposable diaper (folded up tightly on itself and sealed using its own tabs) or dog feces (collected in a tied-up plastic bag) are contained and legally dumped, so too can solid waste mixed with organic bedding from a composting toilet be bagged and dumped. It’s interesting to note that if waste in a composting toilet were treated as it often is in a marine holding tank, with formaldehyde and other chemicals, it would not be classified as solid waste suitable for landfill, but rather as hazardous waste.

Back country hikers and campers who capture and pack out their own waste have long set a precedent for contained solid human waste disposal: the waste elimination and gelling bag concept, commonly referred to as a WAG bag. WAG bags (sold under various brand names) are used to collect and store human waste for later disposal.

Once human waste is deposited in a WAG bag, it is mixed with a powder that gels the liquid urine, covers and adds composting enzymes to the solid waste, and deodorizes the contents. The bags may then be disposed of in a waste stream headed for a solid waste landfill. There are no sterilizing or disinfecting agents present in the gelling powder; the overall effect is strictly containment.

Composting toilets operate in a similar manner to the WAG bag. The organic bedding mixed with the solid waste absorbs moisture (promoting retention of the waste as a solid), covers, deodorizes, and introduces composting enzymes. The commonly used organic media are coconut coir, sphagnum peat moss, pine sawdust, and other organic bedding materials.

It’s important to note that unlike the commercial composting toilets, the DIY sawdust toilet is not designed so that liquid and solid waste are separated. Instead, this toilet depends on periodic additions of sawdust for sufficient absorption. When these contents are dumped, they are a slightly moist, semi-solid clump of sawdust mixed with waste. While the gelling powder found in WAG bags cannot be used with commercial composting toilets, it could be added to the DIY sawdust toilet to further enhance containment and the solid nature of the waste. This powder is sodium polyacrylate, and it is sold widely in hardware stores as an additive intended to solidify leftover paint in cans for disposal.

The solid contents of all compost¬ing toilets should be bagged before disposal into the solid waste stream.

Jim Shell and his wife, Barbara, sail their Pearson 365 ketch off the coast of Texas.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com