. . . and two pocket cruisers that followed

Issue 121: July/Aug 2018

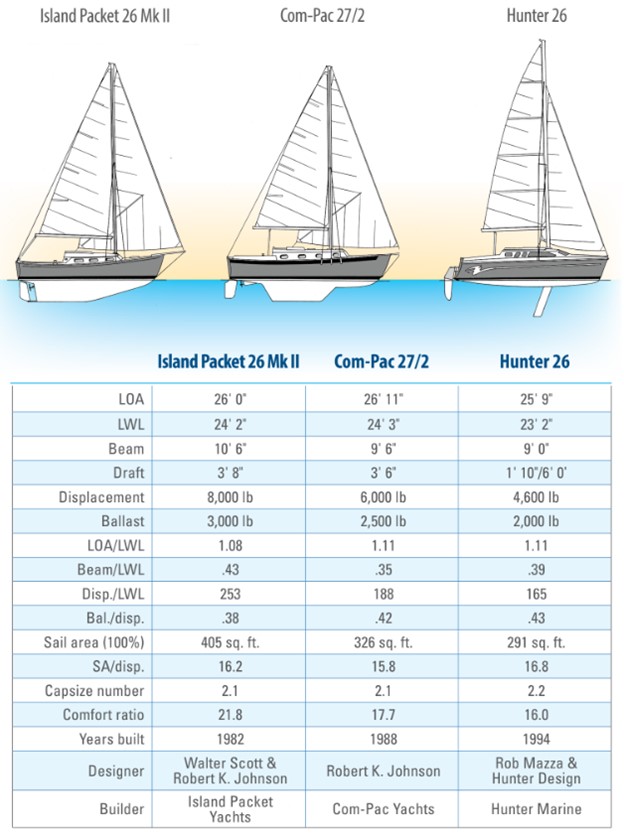

Most sailors, I think, look for evidence of evolution in yacht design, even when the rating rules of the day were written to stymie such development. So, looking at the profiles of these three 26- and 27-footers, the first thing to notice is the transition in hull configuration from full keel, to separate keel and rudder, to no keel at all, in a way reminiscent of the famous silhouettes of the evolution of upright man. But we shouldn’t read too much into that.

The Island Packet 26 started life as a shoal-keel centerboarder designed by Walter Scott. When Robert Johnson acquired the tooling, he made some changes to the centerboard and rudder. For the Island Packet 26 Mk II, he increased the draft substantially but kept the full-length keel. That’s of interest when looking at the Com-Pac 27/2 because Robert Johnson designed it, too, very likely as a development of his earlier work with the Island Packet.

All these boats could be considered pocket cruisers, as they have enough interior volume to accommodate a sailing couple or small family for a week or two. The choice of the water-ballasted Hunter 26 to compare to these two fixed-ballast boats may, at first glance, seem odd. However, I have been in recent correspondence with David Lewis, who has put many cruising miles on his Hunter 26 in the Chesapeake, the Florida Keys, and even the Bahamas. The use of water ballast certainly adds another dimension to the pocket cruiser concept, as it opens up a wider variety of cruising grounds accessible by road and launch ramps. I should disclose here that the Hunter 26 was designed at the time I was head designer at Hunter Marine.

The rigs in these three boats are also of interest. The Island Packet and the Com-Pac both have traditional masthead sloop rigs with fixed backstays, in-plane spreaders and upper shrouds, and double lower shrouds, where the Hunter has a more dinghy-oriented fractional rig, with pronounced sweep to the spreaders and shrouds and no fixed backstay to limit the size of the mainsail. All three masts are deck-stepped, and the Hunter’s can be stepped with the aid of temporary steadying shrouds and a gin pole.

When looking at the numbers for these boats, it’s clear that the Hunter is the smallest of the three. Its LWL is a full foot shorter than those of the Island Packet and the Com-Pac, and it displaces 3,400 pounds less than the Island Packet and 1,400 pounds less than the Com-Pac. However, the displacement/length (D/L) ratio, an indicator of speed potential, favors the Hunter at a sporty 165. The Com-Pac is still competitive with 188, but the Island Packet is relatively conservative with 253.

The power-to-weight ratio, as indicated in the sail area/displacement (SA/D) ratio, also favors the Hunter at 16.8, but the Island Packet and the Com-Pac are not far behind at 16.2 and 15.8. There can be no doubt, though, that the wetted surface of the smaller Hunter, especially with the centerboard raised, will be substantially lower than that of the other two boats with fixed keels, further giving the Hunter the edge in light air.

If we look at sailing stability — the power to carry sail upwind in any sort of breeze — the wider 10-foot 6-inch beam of the Island Packet and the 9-foot 6-inch beam of the Com-Pac will provide greater form stability than the Hunter’s 9 feet. Also, the Island Packet’s heavier displacement (8,000 pounds) and ballast (3,000 pounds) will help it carry that larger 405-square-foot sail plan, even at a ballast-to-displacement ratio of 38 percent. The 6,000-pound displacement and 42 percent ballast ratio of the Com-Pac will also carry its smaller 326-square-foot sail plan well.

Despite the Hunter’s higher ballast ratio of 43 percent, its lighter displacement, even when matched to the smallest sail area of 291 square feet, will make it less competitive than the other two boats upwind in a breeze. That has less to do with ballast weight as it does the ballast’s vertical center of gravity. The other two boats have fixed ballast located low in their keels. The Hunter’s water ballast is located much higher in the boat in tanks between the hull and the cabin sole. This raises the center of gravity of the whole boat, reducing stability upwind. However, the larger mainsail and smaller jib allow more sail to be quickly “dumped” in strong puffs by easing the main.

All three boats have capsize numbers over 2, which is not uncommon for boats of this size, due to proportionately wider beams coupled with lighter displacements. The comfort ratios are lower for the two lighter boats, indicating a quicker motion.

These are three interesting little boats, with one of them being a definite departure in design and styling from the others. All three offer excellent opportunities to get on the water at a reasonable price for any young family starting in sailing or an older couple looking to downsize.

Rob Mazza is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. He set out on his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, working for Cuthbertson & Cassian. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new, and he had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com