Well-drilled junior sailors help save a mast

To the tune of the Beverly Hillbillies theme song . . .

Let me tell you a little story ’bout an engineer named Tom.

Had a little boat that he sailed upon the pond.

Then one day he was going for a cruise,

And what happened next left a pretty nasty bruise!

Figuratively, that is. Indelible. Unforgettable.

Well, Captain told the crew, “Kids, get away from there!”

The big loud noise surely gave them all a scare!

And when the backstay started sagging toward the deck,

Captain then said, “Oh! What the heck?”

In sailing terms, that is.

With “sentence enhancers.”

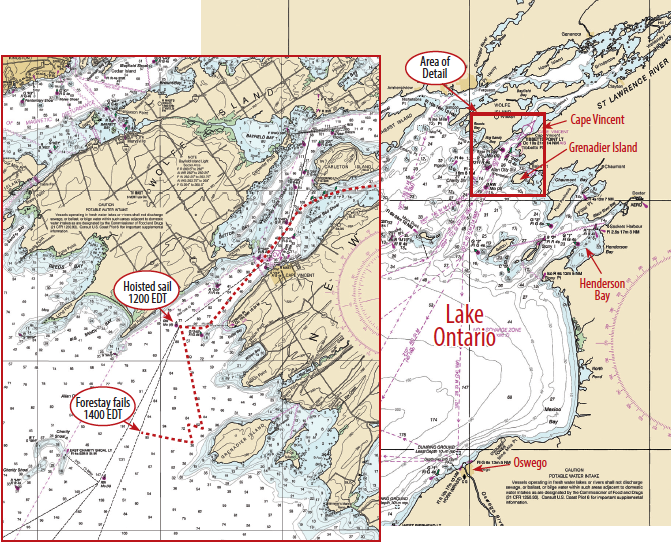

It was just past two in the afternoon on Sunday, July 3. The sun was shining brightly and a few picturesque fluffy white clouds were drifting across the deep blue sky. The heat wave of the prior days had broken with the passage of a cold front and the temperature and humidity had both dropped to comfortable levels. A westerly wind was blowing at 15 to 18 knots and the waves on Lake Ontario had slowly been building to 3 to 4 feet throughout the day. In other words, it was a near-perfect day for Tomfoolery, our 1965 Alberg 35.

We had just tacked onto starboard to clear the shoals off the southern end of Grenadier Island when I heard a loud BANG! The backstay went slack and nearly laid down in the cockpit. Our foresail, furler, and forestay went off to leeward, attached only to the masthead and the furling line.

At that moment, all I could think was, “Oh, no! We’re going to lose the mast . . .”

One week earlier

On the morning of Sunday, June 26, anticipation was in the air. Aboard our fleet of two vessels, Tomfoolery and Seek Ye 1st, a 1973 Islander 36, our crews of experienced junior sailors, all high school students, were ready to depart on an adventure, from the sheltered waters of Seneca Lake, through the New York canals, and onto Lake Ontario to get a taste of voyaging on bigger water. For the boats, it would be a homecoming of sorts, as they were both veterans of those waters.

With masts unstepped and secured on the decks, and with both vessels laden with as many provisions as could be stored, we set off mid-morning. Two days later, our small fleet reached the port of Oswego, New York. The weather had been good and the canal traffic was light. The next day, we stepped our masts, bent on the sails, and set out onto the “big lake” for a cruise, first to Sodus Bay and then to the St. Lawrence River and the Thousand Islands. The cruise was everything we’d expected, so far.

Sunday, July 3

We left Clayton, New York, shortly after 0900 and motored southwest on the St. Lawrence toward Lake Ontario, where we intended to sail south and stop for the night in Sackets Harbor before heading home the following day. The wind was right on our nose as we motored up the river toward the lake. As we got closer to the river mouth, the waves began to grow in size, making for some dramatic photo opportunities.

Upon leaving the river and entering the lake, we bore off a bit to the south. Both Tomfoolery and Seek Ye 1st sailed under jib alone to reduce some of the pitching and rolling motion. We expected that we would clear the Grenadier Island Shoal in just a few hours, then enjoy a nice reach into Henderson Bay.

The loud bang that startled Tomfoolery’s crew later that afternoon also motivated us into action. I disengaged the autopilot and threw the helm over to point the boat downwind to reduce wave action and so the wind pressure on the rigging would be from astern. Training kicked in. The crew of junior sailors slacked the jibsheets to further reduce stresses on the mast and several of them went forward to begin damage control and to secure the now-flogging sail and flailing furler and forestay. While they worked, I made a radio call to Seek Ye 1st, sailing about a half mile from us, to inform them of our plight and to request that they stand by to assist.

The next order of business was to secure the mast to prevent it from falling over. Halyards on the forward side of the mast had become fouled during the gyrations of the forestay and foresail and were useless. Instead, the crew ran the spare main halyard forward, tying it to the anchor platform before tensioning it to minimize the mast’s pumping in the waves, which by now had grown to 4 or 5 feet. Working on the narrow foredeck was a challenge, as the short-period waves caused us to repeatedly bury the bow.

With the mast secured, we attempted to snuff the foresail. This proved extremely difficult, as the furler was by this time seriously damaged and the sail, partially reefed at the time, so tangled that it could not be furled, unfurled, or lowered. Our attempts to manually rotate the entire furler assembly proved futile, as the fouled jib halyard had effectively locked the top of the furler in place. In the end, we freed up the main halyard and led it forward. Timing our movements with the waves, we attempted to wrap the halyard around the still-flogging sail and snuff it against the remains of the forestay and furler. This was marginally effective, but conditions made it impossible to get a good enough angle to snare all of the sail.

After nearly an hour of effort, I radioed Seek Ye 1st to ask if they could spare someone to provide some relief to Tomfoolery’s exhausted crew. Seek Ye 1st came alongside and, using their dinghy as a floating bridge, transferred junior coach Andrea Johnson aboard. At this point, Tomfoolery was drifting down onto the lee shore on Grenadier Island and the depth sounder was showing less than 40 feet. Our attempt to motor to windward proved ineffective, as the partially doused headsail was acting as a brake. Furthermore, the jury rig holding up the mast was under stress from the boat’s motion. We decided to retreat to the closest harbor to leeward that could provide shelter, so we turned around and headed back into the St. Lawrence River.

Three hours later, Tomfoolery and Seek Ye 1st arrived safely in Cape Vincent’s harbor and tied up to the village dock. The captains and crews could breathe again!

Sunday evening

With a few hours of daylight remaining, both crews worked together to clean up the hastily made jury rigging aboard Tomfoolery and to see if she could be rigged sufficiently for a trip back to her home port on her own keel. Here we discovered the extent of the damage, along with what we believe to be the root cause.

It was a disheartening scene. It took almost an hour to unwrap the sail from the furler. Not one section of the furler foil had escaped damage. Each one had a twist, kink, or bend in it. At least one joint had sheared, resulting in the sail being wrapped not just in unequal amounts at different levels of the stay but also in opposite directions. The sail was ripped in several places and seriously stretched out in others.

With the sail unwrapped, how would we get it down? The upper section of the foil had a sharp bend in it right below the upper swivel, which meant the sail wasn’t going to move without someone going up the mast to free it from its halyard. Given the risk of climbing a mast that was not properly supported, I could not send crew aloft with a clear conscience, so I put on my harness.

We cleared off the foredeck and freed a spinnaker halyard to use as a forestay. We led our mainsail halyard forward and cinched it tight as a backup forestay. We also removed the 15-foot, 130-pound solid-spruce boom from the mast to eliminate its tendency to pull the mast aft. This left the spare main halyard for my climb and allowed me to use the boom topping lift as a safety line. After talking through the plan with the crew, I ascended the mast.

Once I was at the top, it did not take me long to detach the headsail from the swivel and help it slide down the damaged furler foils. Before descending, I retrieved the jib halyard from the swivel and pulled it down to deck level where it could be used to help secure the mast.

With the jib and spinnaker halyards secured to the anchor platform as temporary forestays, the crew then used a short line to secure the foil-shrouded forestay to the stem chain- plate to keep it from flailing around during the trip home.

The next day brought light and variable winds and waves of less than 2 feet, which made for a reasonably comfortable passage for our injured boat back to Oswego, where we took the mast down for our trip back through the New York canals to Watkins Glen.

Analysis

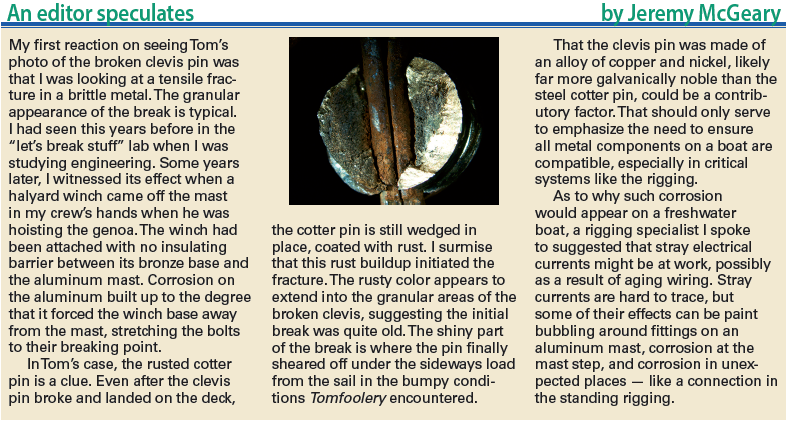

During the cleanup in Cape Vincent’s harbor we found a curious piece of debris on deck. It was half of the clevis pin that held the forestay to the stem chainplate. There appeared to be an old fracture in the pin, just behind the cotter pin, that I judged to be due to fatigue. The stresses on the pin in wind and waves had probably continued to work the pin and propagate the crack (in the photo on page 40, different shades of darkening are visible along the fracture surface) until it fractured completely that Sunday afternoon and allowed the forestay to separate from the boat.

With the bottom of the forestay free, the sail, foil, and forestay then flew to leeward until stopped by the furling line, still attached to the boat. A sudden load on the furler (imposed by the repeated arrested momentum of the flogging sail) probably sheared the lower joint in the furler extrusion. At this point, the lower part of the sail started to furl as the furling line unwound, while the rest of the sail tried to unfurl, causing a number of stresses in the furler and in the sail. It’s likely that the torsional loads on the extrusion, combined with the whipping action of the sail in the wind and the lack of support from a taut forestay, caused the damage to the furler’s foil sections.

Retrospect and conclusions

What is truly frightening about this incident is that I’d inspected the rigging the week prior when we unstepped the mast for the outbound trip in the canals. The shrouds were fine and all the clevis pins appeared to be in good condition. The photo of the broken clevis pin, however, tells a different story. The pin had begun to fail some time before, long enough for the defect to propagate and show signs of corrosion before it parted.

Ultimately, the problem was not the clevis pin, but complacency. Our sailing brethren in salt water and in areas that have year-round boating seasons have learned hard lessons about corrosion and metal fatigue and are, as a result, rigorous in their vigilance to ensure the reliability of their rigging. Living farther north, in fresh water and with low duty cycles on our boats, it’s very easy for us to become complacent with these inspections.

I have made it a habit to drop the mast at least once every five years to inspect all of the rigging, and I make opportunistic inspections whenever the mast is taken down for other reasons. Nevertheless, it’s still easy to overlook details, and tempting to put off maintenance until “later.”

I’ve read numerous accounts of boat owners replacing their standing rigging every five to 10 years to offset the effects of salt water and to prevent incidents like that we just experienced. It stands to reason that freshwater sailors should do the same, but perhaps on a more appropriate schedule, say 10 to 15 years?

Our family purchased Tomfoolery in 1996 — 21 years ago. While we have replaced a few of the clevis pins (usually after the originals were dropped overboard during some other type of maintenance), we’ve never deliberately retired any component of the standing rigging. This means everything is at least 20 years old. As a result of this incident, I replaced all the clevis and cotter pins on Tomfoolery when we got back to our home port of Watkins Glen. The shrouds and stays will see a similar renewal in the coming year, with the old ones to be kept as spares.

Finally, the ultimate introspection: Will I take an extended trip with our junior sailors to Lake Ontario again? Absolutely — they are already talking about where to go next summer. I just hope the trip is a little more boring next time!

Epilogue

Working for a large multinational corporation has its advantages. One is that there is lots of expertise to tap when I have a complex technical question requiring a specialist.

At first I believed the cause of the clevis pin failure was metal fatigue and that I had missed seeing a crack in the pin when I last inspected it. I assumed the staining on the fracture face was due to cotter pin corrosion leaching into a crack. Metallurgical analysis of the fracture face proved otherwise. In fact, it produced a number of surprises.

First of all, it was not metal fatigue but corrosion that caused the failure. As the corrosion propagated across the pin, its structural strength lessened until it could no longer support the load and failed.

Second, the corrosion started on the inside of the clevis pin, in the hole for the cotter pin. This means the corrosion was invisible from the outside of the pin. This is why I didn’t notice it when I last inspected the rigging. Note the detail of the fracture face in the photo. The darker (corroded) areas are on the inside and the outer surface has bits of bright (uncorroded) metal on it.

Finally, the composition of the pin was not bronze as I’d believed it to be. In fact, the pin is a composition not typical of any marine alloy. It was 44 percent nickel, 32 percent copper, 18 percent zinc, and 5 percent chromium.

So it appears that, aside from metal fatigue and corrosion, sailors have yet another thing to worry about, and that is whether the supplier of clevis pins is reputable. This pin came with the boat when I purchased it, so I don’t know where it came from. I purchased all new pins from a known supplier and they are all marine-grade stainless steel.

I sent one of the new pins to my corporate resource for analysis and confirmed that it really is type 316 stainless steel. But type 316 stainless steel is not immune to the crevice corrosion that can lead to this kind of failure. Crevice corrosion is not always visible even with a magnifying glass, and that is a good reason to replace this kind of hardware at intervals appropriate to the waters where a boat is sailed. Don’t be like me and wait for a component failure to be your signal to replace hardware!