Individuals of genius, and technical advances, laid the groundwork

Issue 121: July/Aug 2018

Although fiberglass quickly overtook wood in the 1950s as the predominant material for building pleasure boats, its origins are much earlier. The processes by which it is worked are evolving continually, and a fiberglass boat today, in 2018, is—aside from its smooth and shiny appearance—very different from one built 60 years ago. Even the glass fibers, which constitute the basic foundation of hulls and deck, now are woven strategically. Without these reinforcements, to adopt the more formal term used in the industry, pure resin would be brittle and weak. They perform the same role as steel reinforcement bars in concrete that permit the construction of huge foundations and walls.

Fiberglass boats, and other products like bathtubs and airport people-movers, are essentially comprised of two distinct materials in matrix: glass fibers and a resin, most commonly polyester, but to an increasing degree vinylester and epoxy, which possess different properties. Early experiments in making small boats used natural fibers, such as palm fronds, and glues, such as ethyl cellulose lacquer. But it wasn’t until 1942, when Ray Greene of Toledo, Ohio, was able to obtain samples of glass fibers from Owens Corning Fiberglass (OCF) and a lab batch of polyester resin from American Cyanamid, that the first fiberglass boat, as we know it today, was created—an 8-foot dinghy.

1920s and ’30s

Both products had existed for a few years but never combined in a boat. Corning Glass Works had experimented making glass wool as a filter medium in 1925. Several important steps in its development occurred in 1931, when Owens-Illinois consultant Games Slayter observed crude fibers hanging from the roof joists of a plant that made milk bottles, and again the thought was filters. (OCF resulted from the merger of Owens-Illinois and Corning Glass Works.) A year later, Dale Kleist accidentally produced glass fibers from a molten block using compressed air. That same year, the US Navy began using the fibers as between-decks insulation.

Meanwhile, DuPont chemist Carlton Ellis, working with various acids such as maleic anhydride, added a peroxide catalyst that produced an insoluble solid — but only after he applied heat and pressure. In 1936, he patented his polyester resin. For practical application in boatbuilding, a room-temperature cure was critical, and Dr. Irving Muskat, working at the Wright-Patterson Airfield in Dayton, Ohio, achieved that by adding cobalt naphthenate to the catalyzed chemical cocktail. The polymerization took a long time, however, and was often incomplete, leaving it to John Wills, in 1947, to add 6 percent cobalt naphthenate (common paint drier) before adding the catalyst (MEKP) to the resin.

Now that a room-temperature cure was available, it was possible for any enterprising individual to lay up a boat in a garage. And while much work remained to perfect the materials and processes, the fiberglass revolution was on!

1940s

During World War II, Ray Greene and others, including John Wills and Gar Wood Jr., son of the famous raceboat driver, worked on military projects developing objects like radomes and air-sea buoys for rescuing downed pilots. Seeking light weight and strength, they were forced to look beyond wood and metal to the promises of synthetic composites.

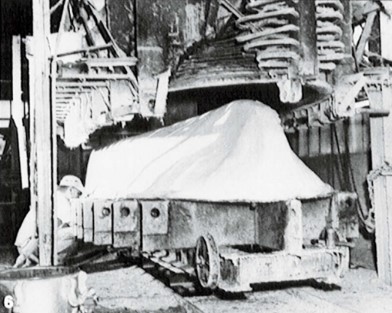

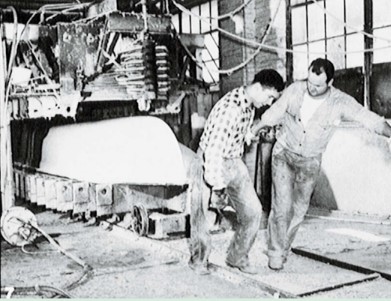

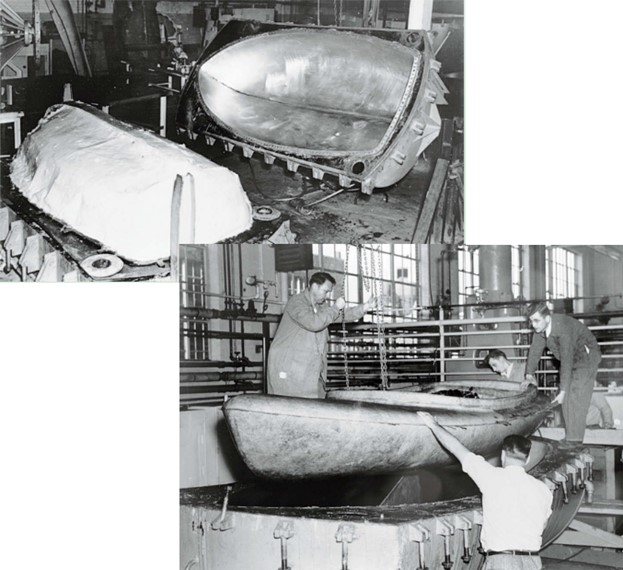

Dr. Muskat developed one of the first processes that didn’t rely on manual wetting-out of the reinforcements. In the Marco Method, named after Muskat’s Marco Chemical Co., a metal male mold was set upside down on the shop floor, glass fibers were distributed over it, and a slightly larger matching metal female mold was placed on top. Catalyzed resin was then drawn up from a reservoir into the fibers by means of a vacuum pump. Problems were at least twofold: voids resulted if the resin didn’t thoroughly saturate the fibers, and there was no guarantee the resin would fully cure.

Nevertheless, a number of builders adopted the Marco Method, including Gar Wood Jr., who built 2,000 16-foot outboard-powered boats called the Gar Form. He called his material Nautilite, boasting that “it is waterproof, heat and cold resistant, and does not warp, corrode, become waterlogged, shrink, or expand.” His were possibly the first production fiberglass boats ever built. The year: 1947.

Concurrently, Taylor Winner of Trenton, New Jersey, was building three 28-foot fiberglass patrol boats and personnel carriers for the US Navy. Half-inch-thick aluminum female cavity molds were used for the hulls and decks, formed over wood plugs and hammered into shape. Others using matched metal molds were Palmer Scott and Carl Beetle, both of Massachusetts. Winner may have been the first to mix pigments into the resin to obtain the desired color, gray in the case of the Navy. Commercially produced gelcoat didn’t arrive until the 1950s, the first probably being GelKoat, introduced by Glidden in 1953.

On the West Coast, in Hollydale, California, Curtis A. Herberts, a German immigrant, operated a machine shop specializing in aircraft parts. He met a fellow named Tiny Hardesty, who had supposedly built a fiberglass and polyester boat as early as 1943. The term “fiberglass” was sometimes used loosely; one source says Herberts’ Wizard Boats used spun glass, glass mat, sisal, and a final layer of bleached muslin for a smooth finish. Involved in the project was aeronautical engineer Brandt Goldsworthy, who invented pultrusion. He built a flying car with phenolic resin and natural fibers in 1946, the first fiberglass car body for Howard “Dutch” Darrin, and more than 300 runabout hulls for Triangle Boats under the name of his Industrial Plastics Corp.

As the decade closed, fiberglass boatbuilding was gaining momentum on both coasts after years of experimentation with other materials, such as cotton impregnated with Bakelite laminating resin and honeycomb paper as a backing for fiberglass. By now, OCF was recommending fiberglass cloth as the primary reinforcement, plus at least one ply of mat for a total laminate thickness of 1⁄2 inch for a 12-foot boat.

The Marco Method presaged advanced closed-mold systems such as SCRIMP (Seemann Composites Resin Infusion Molding Process) of the 1990s, but builders came to prefer simpler processes: contact male molds of plaster of paris, followed almost exclusively by contact female molds, first of plaster and then of fiberglass, taken off a male plug.

1950s

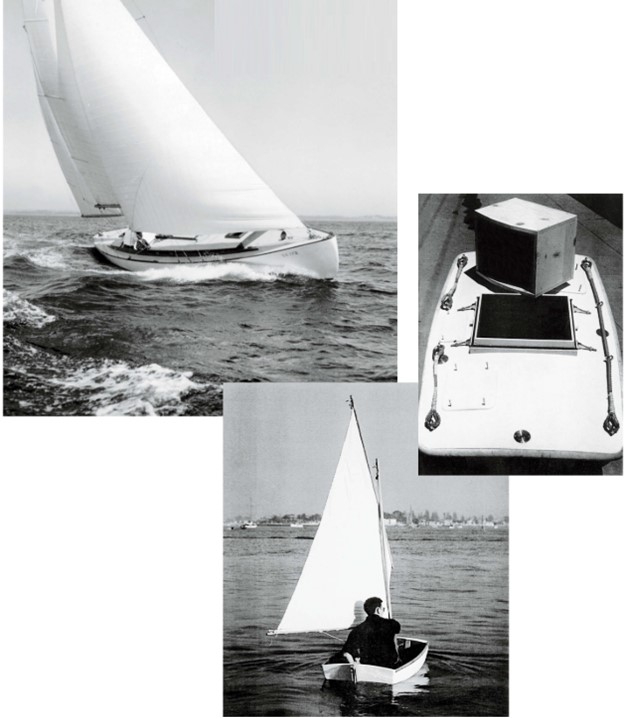

More than one early glass boat was “splashed” from a wooden hull, which is what Leo Telesmanick said he and Palmer Scott did when their supply of plywood dried up in 1952. They cleaned up one of their finished wooden hulls and made a mold from it for the Southern Massachusetts Yacht Racing Association (SMYRA), and named it the Smyra. It became a forerunner of the popular Rhodes 19 keelboat.

Cape Cod Shipbuilding bought the jigs, forms, and patterns for all of the Herreshoff Mfg. Co.’s small boats, such as the Bull’s Eye and S Class. In 1949, after 50 years of building wooden boats, it began the conversion to fiberglass, employing glass mat from the Ferro Corp. and American Cyanamid’s 4128 resin. Only mat was used in the laminate, which made the boats light but flimsy; it was said that standing the MK Dinghy on its side sometimes drove the wooden thwart through the topsides.

Many builders claimed to be the first to mold a fiberglass boat, mainly because no one knew what others were doing. In an early effort to cross-pollinate fiberglass boatbuilding technology across the country, The Anchorage’s Bill Dyer, of Warren, Rhode Island, traveled to California at the end of the war to see what builders were up to on the West Coast. There he met some of the aforementioned—John Wills and Tiny Hardesty. He might also have met Bill Tritt, the first person to make a fiberglass mast and boom 40 years before Garry Hoyt popularized unstayed composite rigs with his Freedom line of sailboats. Tritt’s early boats were laid up over male plugs coated with axle grease as the release agent. By 1958, his Glasspar company, virtually forgotten today, was building an astounding 10,000 boats a year.

On returning to Rhode Island, Dyer set about converting his shop to fiberglass. Among his most notable achievements was the construction in 1951 of the first fiberglass auxiliary sailboat, the 42-foot Arion, which is still sailing after several rebuilds. Arion’s laminate schedule was 10 to 21 layers of cloth with some mat reinforcements in high-load areas. In 1957, Dyer built four 23-foot deep-V powerboats designed by C. Raymond Hunt, prompting Dick Bertram to commission a 31-foot version, which famously won the 1960 Miami-Nassau Race and launched the Bertram Yacht Co.

Vince Lazzara, a Chicagoan who owned a foundry and would later co-found Columbia Yachts in Southern California, and then Gulfstar after moving to Florida, entered the boatbuilding industry by partnering with Fred Coleman, who’d had William Garden revise the plans of the pre-World War II Phil Rhodes-designed wooden Bounty for fiberglass construction. A layer of cloth and seven to 10 layers of woven rovings were laid up in a two-piece fiberglass mold, and Styrofoam stiffening beams were then molded into the hull. The ballast was precast iron set into the hull cavity in epoxy resin. Coleman boasted: “It will not corrode, rot, or rust. It is fire-resistant and free from deterioration from exposure or weather. Worms and dry rot do not bother it.” The yacht was exhibited at the 1957 New York Boat Show for $18,500. Among Lazzara’s contributions was experimenting with “pre-pregs”—reinforcements saturated with resin and refrigerated until they are needed for laying up in the mold.

In Portland, Oregon, five sailors pooled resources and cash to develop the Chinook 34, selecting woven rovings and two layers of mat for a smoother finish. Woven rovings, developed by Ira Dildelian, who’d converted an old carpet mill, build thickness quickly but absorb a lot of resin. Partner Wade Cornwall said they maintained a 50:50 glass-to-resin ratio. Today, closed-mold processes, such as infusion, achieve ratios of 70:30 for lighter, stiffer panels.

A significant development was molding the major interior features in a single fiberglass pan or liner, eliminating many man-hours needed for hand-cutting and assembling plywood parts for berths and cabinets. In large-volume production, tooling costs are quickly amortized.

French builder Henri Amel was probably the first to mold liners, and did so with his Super Mistral 23. When authorities, skeptical of fiberglass, wouldn’t give Amel a license to exhibit the boat at the 1958 Salon Nautique de Paris, he glued wood strips over the hull to disguise it.

Everett Pearson was very influential in advancing the quality of pleasure boats, sail and power (see his obituary in the March 2018 issue). He and his cousin Clint Pearson started their company with a series of dinghies and runabouts, then, in 1959, built the first really successful fiberglass auxiliary sailboat, the 28-foot 6-inch Triton. While the materials were standard mat and woven roving set in polyester resin, the thickness of the uncored hull is of interest. It’s popularly thought that early builders copied wooden-boat scantlings. Everett did not. He told how an executive from chemical giant W. R. Grace & Co. one day wandered into the shop and left offering to test panels. Based on designer Carl Alberg’s calculated loads on the hull, and factoring in “at least a 3:1 safety factor,” Everett adjusted the laminate schedules accordingly.

1960s

Along with George Cuthbertson and C&C Yachts, Pearson Yachts was an early proponent of coring hulls with balsa wood to achieve the I-beam effect of distributing stresses. Pearson Yachts began using balsa boards with the grain lengthwise, but on noting how moisture migrated along the grain, Everett began cutting the wood so he could lay it on the end-grain, and hung a panel of balsa-cored glass off his dock to demonstrate how little water migrated through the core when oriented this way. The 40-foot Cuthbertson-designed Red Jacket, which won class and overall trophies in the 1967 and ’68 Southern Ocean Racing Conference (SORC), is thought to be the first boat built with balsa core in both hull and deck.

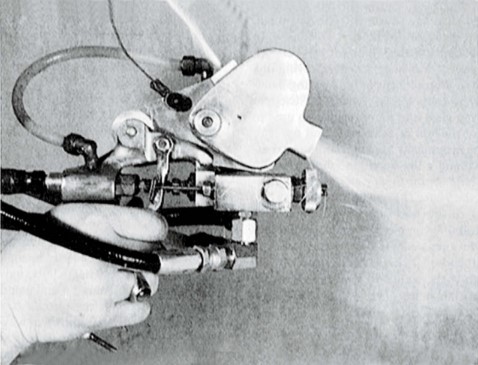

Hand-laid reinforcements, wetted out by pouring or spraying resin and then working it in and compressing the glass (consolidating) with a squeegee, became the most common method of building quality boats. Of course, much depended on the skill of the laminators, and voids and dry spots were not uncommon. The search for a faster method led to the development of the chopper gun, where a continuous thread of glass is fed into a handheld machine that chops it into short lengths and mixes it with catalyzed resin. Before Dick Bradley developed his Bradley Gun, other sprayers delivered resin or glass, but not simultaneously. The Bradley Gun weighed 16 pounds and had to be suspended from the ceiling by a cable. Later models by Glas-Craft and Binks were lighter and more efficient. A laminate made with chopped fibers only is not considered suitable for larger boats, but small boats can be satisfactorily built with a chopper gun. Even on large boats, the gun is useful for forcing glass into difficult corners and for applying a preliminary skin-coat layer into a mold to fix the gelcoat and help prevent print-through.

1970s

In the 1960s and ’70s, 1½-ounce mat and 24-ounce woven roving reinforcements were common in most shops. Bill Shaw, a designer who became general manager and later an owner of Pearson Yachts, said a lighter 18-ounce woven roving helped prevent print-through, but that during the 1970s materials and processes were otherwise fairly static. He felt that the energy crisis of that period required manufacturers to adjust the chemistry of their products, first causing gelcoat cracking and then blisters. The latter, according to lab tests by Rick Strand and reported by Practical Sailor in 1990, were largely caused by mat preventing silica platelets in the resin from migrating through and by poor bonding of gelcoat and skin-coats. Repair yards charged thousands of dollars to peel layers of glass off a hull to remove the wet areas and apply barrier coats of epoxy resins, which had proven to be much less hydroscopic. Vinylester resins, less expensive than epoxy but with similar properties, also came into use.

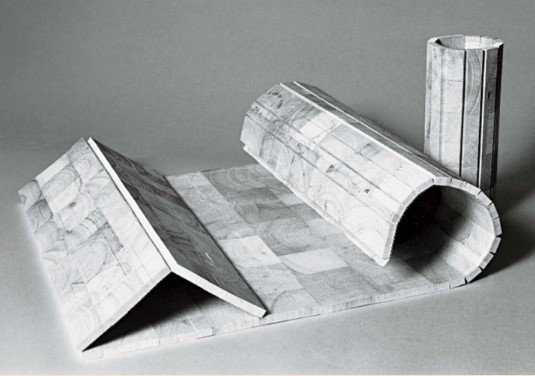

And while end-grain balsa continued to be an effective core material from the standpoint of both mechanical properties and cost, new materials began to appear. The first yacht built in the US with a core of Airex, an expanded PVC (polyvinyl chloride), was Questar, a 50-foot ketch designed by Jay Paris and launched in 1972. Other new core materials included cross-linked foams, such as Divinycell and Klegecell; Corecell, a linear polymer foam; and Nomex, a honeycomb product used in building the Stiletto catamaran in the early 1980s. Some did not possess the stiffness of balsa, which is desirable in hulls, and others deformed when overheated, particularly in dark-colored decks. Today, Corecell is probably the most common alternative to end-grain balsa.

Materials and methods

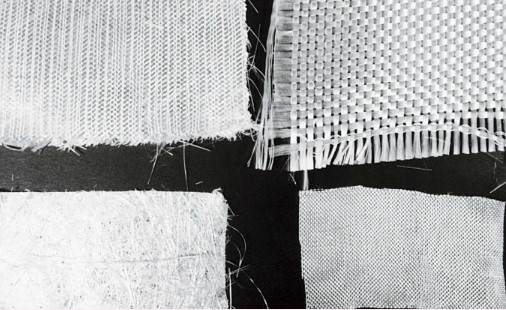

Mat, cloth, and woven roving are basically isotropic materials (with uniform strength in all directions), but a significant improvement to reinforcements came in the early 1980s. With the development of unidirectional fabrics, computer analysis (such as FEA, or finite-element analysis) of loads on hulls enabled engineers to identify the high-stress areas and specify a fiberglass product with the fibers aligned in the direction of those loads. Typical orientations are 0, +45, 90, and -45 degrees. Here is the lamination schedule for the bottom of a single-skin production 35-footer built in 2017:

Gelcoat

2-ounce chopped-strand mat

1x 1708 E-glass double bias w/mat

3x 3610 E-glass biaxial w/mat

1x 3408 E-glass weft triaxial w/mat

Other areas of the hull, especially the topsides, have a different schedule. E-glass (electrical grade) is the most common fiber used in boatbuilding; more expensive S-glass (structural grade) with some superior qualities is not often employed. Carbon fibers are increasingly added to the mix to provide greater strength in certain applications.

Concurrent with the development of more efficient weaves was the recognition that higher glass-to-resin ratios saved weight and money. Vacuum bagging provided a way to improve on the 50:50 ratios typical of most early laminates. The mold, with the wetted-out reinforcements inside, is covered with a 5-mil clear plastic bag, and a small pump pulls a vacuum of about one atmosphere that consolidates the laminate and eliminates voids. Resin-infusion processes, such as SCRIMP, elaborate on vacuum bagging by drawing the resin by vacuum into the dry reinforcements via numerous small tubes. The benefit is severalfold: high resin-to-glass ratios of up to 70:30, and curing inside the bag, with VOCs (volatile organic compounds) expelled from the workplace, thereby protecting the health of the shop crew.

While room-temperature-curing resins were a huge advance in the evolution of fiberglass boatbuilding, even today some resin systems, such as epoxy, do not achieve full cure and strength until their temperature has been elevated, in some cases to 160°F or higher. To do this, the hull or part must be placed in an autoclave or oven equipped with heaters to slowly ramp up the temperature to the desired level and then evenly lower it. Most of the large carbon fiber yachts built for offshore racing are so constructed.

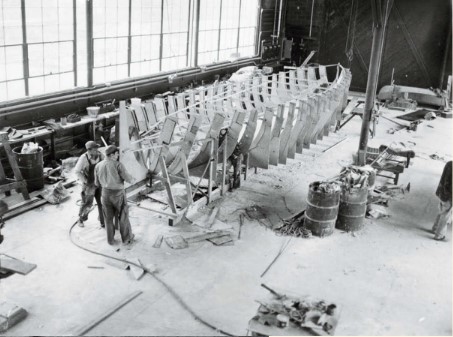

For hundreds of years, hulls and many other components of boats were lofted full size on the loft floor from lines transferred from drawings or models. The accuracy of the build depended on the skill of the loftsman. While still practiced, lofting is giving way to more sophisticated mold-making techniques.

Today, a plug can be milled from a giant block of foam with a computer-controlled 5-axis router, accurate to within thousandths of an inch. Janicki Industries, founded in 1993, was one of the first companies to make CNC-milled plugs for aviation, aerospace, and boatbuilding.

The word “fiberglass” has largely given way to the new term “composites,” which more accurately reflects the multitude of materials that comprise a given product. Composites are replacing more traditional materials, such as aluminum and steel, in an ever-expanding range of industries, from vehicles to bridges to telephone poles to airplanes — future applications for the materials seem limitless.

As for boats, building them today is a lot more complicated than the “bucket and brush” method that dominated for decades. Now, thanks to advancing technologies, composites engineers optimize a structure with a recipe of reinforcements, cores, and resins resulting in the desired properties for strength, stiffness, modulus of elasticity, weight, and cost. The benefit for boat owners is a higher-quality product that performs better and lasts longer.

Dan Spurr is a contributing editor with Good Old Boat and an editor at large with Professional Boatbuilder. He is the author of seven books on boats and sailing, including Heart of Glass, about the fiberglass boatbuilding industry, and was formerly senior editor at Cruising World and the editor of Practical Sailor.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com