Losing the steering is not necessarily the end of steering

Losing the steering is not necessarily the end of steering

Issue 126: May/June 2019

Loss of steering is possibly the most common reason boats sailing long offshore passages are abandoned. The inability to make progress toward a destination —any destination — is life-threatening. A boat sailing inshore faces the more immediate risk of being driven ashore, and because encounters with flotsam or underwater obstructions are more likely near shore, so too is the likelihood of losing steering. Few near-shore sailors carry an emergency rudder because of the cost of the gear and the stowage space it would take up. There is also the physical challenge of wrestling an emergency rudder into position, a task that would be difficult enough in moderate weather even with the help of crew, and perhaps impossible for a singlehander. The alternative, in many instances, is an expensive tow to a repair facility. But there is another option: drag steering.

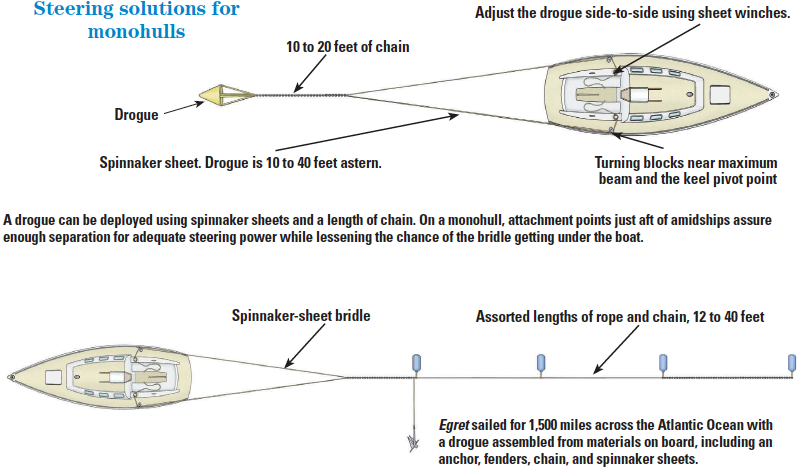

Reasonably effective drag-steering systems can be rigged using gear that’s normally on board, and can be deployed safely by one person, even in challenging conditions. The principle of drag steering is the same as that of steering a canoe by dragging a paddle: drag the paddle on the side toward which you want to turn the boat. The closer the paddle is to the natural pivot point of the boat — the keel if the rudder is gone and a little farther aft if it is still there but immobile — the quicker the turn and the less drag required. Holding the paddle farther outboard helps as well.

An anchor hanging a few feet below a fender large enough to float it will serve for the coastal sailor. I’ve tested this rig, and though heavy to lug around, once deployed it worked about as well as a drogue. If more braking is needed for good control, a second anchor below a second fender 20 feet from the first anchor will provide it. After the rudder on Egret, a Sweden Yachts 39, snapped off in the Atlantic Ocean, her crew sailed her for 1,500 miles with this kind of rig.

I have tested the anchor-plus-fender drogue on multihulls and on a 27-foot monohull in 10 to 12 knots of wind. There was little difference in function; although monohulls have less beam and thus less leverage, they also pivot more easily around their keels.

Steering with a drogue

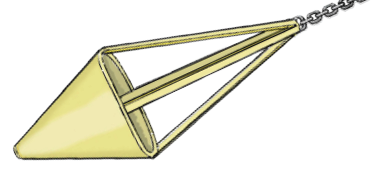

A more sophisticated emergency steering method is to tow a drogue. Several brands are available commercially. They are lightweight, easy to stow, and for steering can be rigged using spinnaker sheets or other lines usually carried on board. They are stable in strong conditions, have been proven during ocean crossings, and are approved by US Sailing for boats taking part in offshore races.

I have tested some of these steering solutions on large and small boats, multihulls and monohulls, and I have disproved the often-voiced opinion that drogues are only usable for off-the-wind sailing. With a properly rigged drogue steering system, I’ve been able to sail slightly to windward in good conditions, with the true wind just aft of the beam in near-gale conditions, and on any course I wanted if I used the engine. Although I wouldn’t try to steer right into a slip, straightforward channels and most harbors present little difficulty.

I have tested the Delta Drogue, Galerider, Seabrake, and small Shark, and they all work about the same. For steering, an 18-inch diameter works for boats 30 to 35 feet, and a 24-inch diameter for boats 35 to 40 feet. For equal drag, the Galerider needs to be one size larger, as it’s more like a net. These drogues are also used for slowing a boat in gale conditions, but a storm device would need to be larger and more heavily rigged than a drogue used purely for steering.

Rigging a drogue

For maximum maneuverability on a monohull (when motoring on a river, for example), attach the bridle control lines at the widest part of the boat and outboard of its pivot point, which is generally a short distance aft of the mast and near the center of the keel. Be aware, however, that when the bridle is attached this far forward, the lines can easily wander under the boat. This is not a problem if the rudder is gone or if the boat’s speed is steady, but it presents a significant fouling risk if the rudder is still there, the seas are lumpy, and sailing progress is irregular. The best compromise location is about halfway between the mast and the transom, where there is enough beam for leverage but less risk of the bridle getting under the boat.

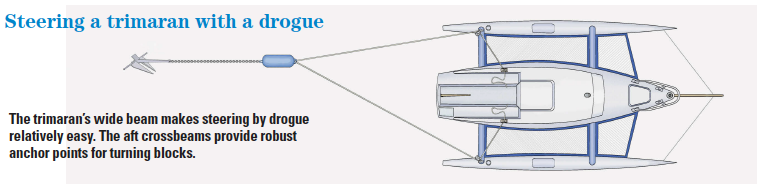

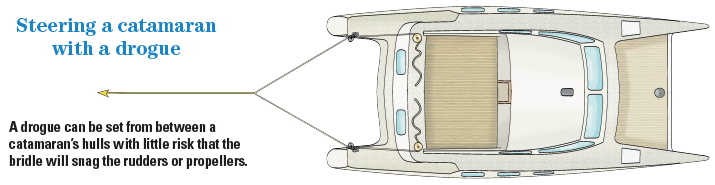

On multihulls, the turning blocks should be near the transoms, as the leverage there is sufficient and the bridle will stay out from under the boat.

In light to moderate winds, the drogue should be pulled in as close to the transom as practical; steering inputs are more immediate and the drogue is lifted up near the surface, reducing drag and improving speed and pointing.

Deploying a drogue

When deploying a drogue, make the bridle arms equal in length and set them at one boat length. It’s better to start off on a relaxed downwind course and with the drogue a little too far back than to risk sudden turns and tangling lines under the boat while setting up the rig. Deploy the gear at full extension and head off on a broad reach. Grind the bridle in closer for better speed and steer a higher course only after the boat is making steady progress. Never underestimate the risk of getting a line under the boat when it’s in an awkward, rolling, drifting posture. I did this several times. So long as there are no knots at the ends of the lines you can generally just let go of one side of the bridle, recover the drogue, and start over. If things aren’t going well, consider reefing the mainsail or dropping it.

In strong conditions, the wind will blow the drogue right back in your face if you try to pitch it over the stern. Lower the chain into the water first, then the drogue, and then the bridle. The Galerider’s web design catches less air than the others, and even though the maker does not recommend weight, it was easier to handle in a strong breeze with 8 feet of chain attached. The small Shark, with an anchor on the tail, is the easiest to handle.

As the wind increases, ease the drogue farther back from the boat to increase drag (steering force) and to keep the drogue stable — in steep waves, they tend to surface and skip around. In one of my tests, with the 8-foot chain leader and the spinnaker sheets at full extension, the drogue was about 60 feet behind the boat and was stable in winds up to about 25 knots.

If the wind reaches a sustained 25 to 35 knots, more scope will be needed. This is where inshore boats are at a disadvantage. These conditions need a 100-foot rode extension between the chain and the bridle. This could be cobbled together with docklines or spare sheets, but the knots used to connect them will cause problems at the deck edge and winches when deploying the drogue or hauling it back in. Metal shackles definitely are not suitable, as they cause point loading and require thimbles, which can shift and cut the rope. Ideally, the lines should be connected by interlocked eye-splices, as they can pass around a winch drum if the line is hand-tailed. This would mean carrying dedicated drogue rodes with eye-splices in each end.

Strength and materials

Spinnaker sheets are long enough and strong enough for emergency steering. Nylon and polyester are both fine, but nylon is not necessary for shock absorption; in a surge, the drogue will simply pull through the water faster, gradually increasing the force. With polyester, due to its lower stretch, the steering response is better and yawing and surfing are reduced.

Steering under sail

Steering under sail

Smaller drogues allow better speed in light conditions, but they require earlier reefing, and the mainsail must be dropped when sailing off the wind in even moderate conditions. That’s not much of a hardship when power is plentiful.

In light conditions, a larger drogue can be depowered by hauling it in to a very short scope and lifting it partially clear of the water. Used in this way, the Galerider is smoother to adjust than other drogues because it strains the water rather than plowing through it. Anchor-and-fender drogues do not depower when hauled in short, but the drag is a function of the number of anchors and fenders being towed. I have found that, once the sails and drogue are balanced and adjusted, course stability under sail was generally very good, although yawing would increase with the wind strength: 10 to15 degrees in light weather and 10 to 25 degrees in stronger conditions.

To maintain control if the wind picks up, reef earlier than usual. Start with the mainsail, and if the rudder is missing and no longer contributing to lateral plane, keep the mainsheet traveler lower than normal on all courses. As soon as the true wind moves aft of the beam, strike the main. Expect to lose 1 to 3 knots of boat speed — more to windward in light conditions, and less on a broad reach in a breeze.

To maintain control if the wind picks up, reef earlier than usual. Start with the mainsail, and if the rudder is missing and no longer contributing to lateral plane, keep the mainsheet traveler lower than normal on all courses. As soon as the true wind moves aft of the beam, strike the main. Expect to lose 1 to 3 knots of boat speed — more to windward in light conditions, and less on a broad reach in a breeze.

As the wind strengthens, pointing ability decreases rapidly. This is partly due to the increased drag, but mostly I just couldn’t stay in the groove in winds above 15 knots. By 20 knots, I gave up on windward courses. This is much more distinct than the ordinary loss of windward ability in waves. Running the engine at low rpm dramatically improved directional stability on both reaching and windward courses.

I had no trouble flying an asymmetric spinnaker down- wind in less than 15 knots wind, where it can generate more speed than the genoa. The main had to be furled to maintain balance and the spinnaker slightly over-sheeted to increase stability.

I had no trouble flying an asymmetric spinnaker down- wind in less than 15 knots wind, where it can generate more speed than the genoa. The main had to be furled to maintain balance and the spinnaker slightly over-sheeted to increase stability.

Steering under power

All of the drogues were able to provide controllable steering when under power at a range of speeds on flat water and in moderate waves. In winds and waves over 20 knots, yawing became considerable.

Bent rudder

If the rudder is bent to one side, the situation is more challenging than when it is absent. I simulated this by setting the helm 60 percent to one side. More drag is required to keep the boat straight, speed is reduced, and the ability to sail to windward is eliminated on one tack. In strong conditions, a bent rudder will require a large drogue and only off-the-wind courses will be possible, although a considerable range is still practical. Under power, all courses are possible.

Recovery

Never underestimate the risk of getting a line under the boat when recovering a drogue. While it’s possible to ease the work of hauling in the drogue by backing the boat under power, the risk of fouling the prop or rudder is considerable. Use very low rpm to slow the boat, leaving some tension on the rode while the majority of the line is hauled in, and then put the gearshift in neutral while bringing the last 20 feet aboard. If the wind is dying and the waves are steep, the load is generally very light on the back slope of a wave, and 5 to 10 feet can quickly be hauled in with the passage of each wave. Lock the rode down as the tension comes back on and wait for the next lull or back slope. Don’t let the line get under your feet or around a wrist; there can be a lot of surging and the loads can be dangerous even in light winds.

Conclusions

Until I struck that log and felt the helplessness of sailing in circles, I believed drogues were for ocean crossings. How stupid to become utterly helpless because one bit of metal is bent 2 degrees. However, I was encouraged when I saw just how well a drogue can steer, even one made from an anchor and a fender.

I recommend practicing steering with a drogue or drag device, first in fair weather and then on a not-so-nice day. The time to iron out the wrinkles in the system is not in the minutes after the rudder bids farewell. And that applies to the coastal and the bluewater sailor alike.

When Steering Loss Became Personal

Loss of steering is not just hypothetical to me . . .

A 15-knot breeze had been driving my PDQ 32 catamaran down Chesapeake Bay at 8 to 9 knots all morning when I heard “Wham!… wham!” Shoal Survivor lurched slightly to port, telling me I had struck something substantial with that hull, but a quick glance around

the boat revealed nothing. I hadn’t struck bottom; I was in 50 feet of water. I eased the sails and dashed below to check for water in the bilge and crash tanks (thankfully none). The autopilot beeped an off-course alarm, and when I disengaged the pilot to make a manual correction, the wheel would not budge and the boat continued very slowly to port . . . and toward the shore.

I was able to resume my proper course by adjusting sail balance and adding a little drag to the leeward side by lowering a retractable outboard motor. I selected an alternative downwind destination, and when I was close enough, lowered sail and played the twin engines against each other to negotiate the channel. After anchoring, I donned a drysuit and examined the bottom, to find only scuffed bottom paint and a rudder stock that had been bent just enough that the blade scraped the hull. I disconnected that rudder and finished the cruise using the other with no effect other than mushy steering. If I’d not had twin rudders, my options would have been

repair at a yard far from home or a long-distance tow.

Running-Pendant Bridle

I have read several articles and papers that suggest rigging a single line from one quarter and fitting a snatch block to it attached to a pendant led to the opposite quarter. The idea is to rig a bridle that is adjustable both in length and position.

I have tried this when testing with the 32-foot catamaran. In light winds, when I didn’t need an extended rode, it almost worked. However, when the wind and waves picked up and the boat began

yawing, it failed every time. When I pulled the drogue to the rode side, the pendant would snap forward to the transom, trapping the boat beam-on to the waves. The force on the drogue increased

and the force on the pendant winch became nearly double the actual drogue tension. To regain control, I had to release the pendant, start the engines, and use the rudders, which is obviously cheating. Without a working rudder, control can only be regained by rerigging the bridle.

Resources

Para-Tech Delta Drogue: seaanchor.com/delta-drogue

Galerider: landfallnavigation.com

Seabrake: burkemarine.com.au/pages/seabrake

Shark: para-anchor.com/pro.stormdrogue.html

Drew Frye draws on his training as a chemical engineer and pastimes of climbing and sailing when solving boating problems. He cruises Chesapeake Bay and the mid-Atlantic coast in his Corsair F24 trimaran, Fast and Furry-ous, using its shoal draft to venture into shallow and less-explored waters. His book, Rigging Modern Anchors, was recently published by Seaworthy Publications.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com