. . . and a couple of companion centerboarders

Issue 120: May/June 2018

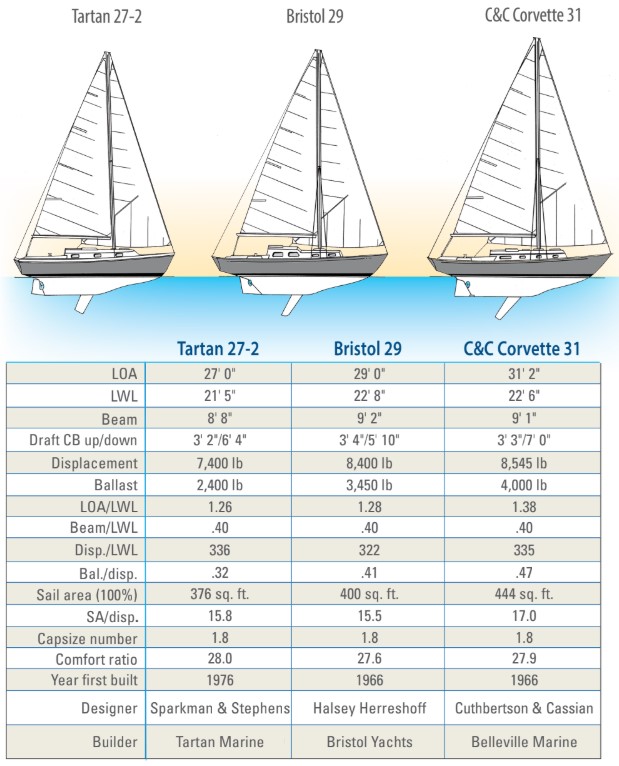

I have to admit that I like centerboarders. It was no accident, after sailing International Fourteen Foot Dinghies (with centerboards) for more than 30 years, that our first “big” boat was also a centerboarder. My wife, Za, and I have now owned Trillium, our C&C Corvette, for more than 20 years, and are very well aware of her many idiosyncrasies. She is overpowered in heavy air and underpowered in light air, does not maneuver well, and she is hardly light on the helm. But what she does offer is classic good looks, a large cockpit, acceptable accommodations for two, and, above all, the option of shoal draft with the board raised, which compensates for a lot of her shortcomings.

The heyday of the full-keel/centerboard configuration was in the 1950s, when Cruising Club of America (CCA) rule-influenced raceboats like the Sparkman & Stephens-designed Finisterre, the Rhodes-designed Carina, and the Cuthbertson-designed Inishfree were chalking up impressive race wins on both salt water and fresh. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the original 1961 S&S-designed Tartan 27 would incorporate this configuration, which also capitalized on the cruising potential offered by the shoal draft and centerboard.

When it came time to “upgrade” the Tartan 27 in 1976, the hull remained unaltered, retaining the cruising advantages of the centerboard, even when the racing advantages had long since diminished due to changes made in the CCA rule for exactly that purpose. To improve the cruising amenities of the new T27-2, headroom was increased with the addition of 4 inches to the freeboard, and a further increase incorporated in the height of the house, especially forward. The increase in freeboard was achieved entirely in the new deck tooling. This is a clever rationing of resources. Since a new deck mold was already required, why not incorporate the increased freeboard in one set of tooling only, rather than making an expensive alteration of the hull mold as well? As a result, the hull-to-deck joint is not actually at the intersection of hull and deck but at a line below the sheer and running roughly parallel to it. This essentially creates a style line, which helps to mask the higher freeboard.

The two boats I’ve chosen for comparison, the Halsey Herreshoff-designed Bristol 29 and the Cuthbertson & Cassian-designed Corvette 31, are also CCA-influenced designs introduced in the mid-’60s, both incorporating centerboards. Remember, this was at at a time when the configuration of fin keel and separate rudder was about to make its mark in fiberglass production boatbuilding with the introduction of the Lapworth-designed Cal 40 in 1963. However, for yacht-club racing, the keel/centerboard is still a viable option, especially under PHRF, as Za and I can personally attest with Trillium.

In this comparison, I have used the original sloop rig for the 27-2, not the modified rig employed on our review boat. Looking at the rigs, it is revealing to note how similar they are. The aspect ratios of their mainsails are all about 2.3:1, and their foretriangle aspect ratios are a little above 3:1. This is well before the era of IOR “ribbon” mainsails. The long boom may well contribute to the dramatic buildup of weather helm on the Corvette, and I suspect the other two boats, on a heavy-air reach.

If we are to measure boat size by the length of the waterline (LWL) and displacement, then the Tartan is certainly the smallest of the three, being more than a foot shorter and a thousand pounds lighter than both the Bristol and the C&C. However, this still results in very similar displacement/length (D/L) ratios of 336, 322, and 335 respectively. The 27-2 also has the smallest sail area at 376 square feet, compared to the Bristol at 400 and the Corvette at 444. This yields similar modest sail area/displacement (SA/D) ratios of 15.8 and 15.5 for the Tartan and the Bristol, but a more performance-oriented 17.0 for the Corvette. However, not recorded in these comparisons are the ratios of sail area to wetted surface for these three full-keel boats, which would be much lower than those for similar fin-keel boats. Indeed, Za and I can attest that, even with an SA/D ratio of 17, the Corvette feels stubbornly glued to the water in light air.

Despite the wider beams usually associated with centerboards, and the lighter displacements, often due to lighter ballast, all three boats have capsize numbers of 1.8, safely under the 2.0 threshold. The comfort ratios are also very consistent in a tight range between 27 and 28, indicating a comfortable motion.

All three boats sport attractive sheerlines and balanced overhangs, but will I betray my own prejudice if I were to say that, to my eye, the Corvette is the prettiest of the three?

Rob Mazza is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. He set out on his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, when he began working for Cuthbertson & Cassian. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new, and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com