A meditation on mountains helps define an evocative passion for sailing.

Issue 130: Jan/Feb 2020

At 45 degrees North, our bedroom overlooks an old neighborhood with mature hardwood and conifer trees, just a block from upper Lake Michigan. When I wake, the first things I see are the branches, good telltales for the state of the wind. About half the year, the first thing I think is: Would it be a good day to sail?

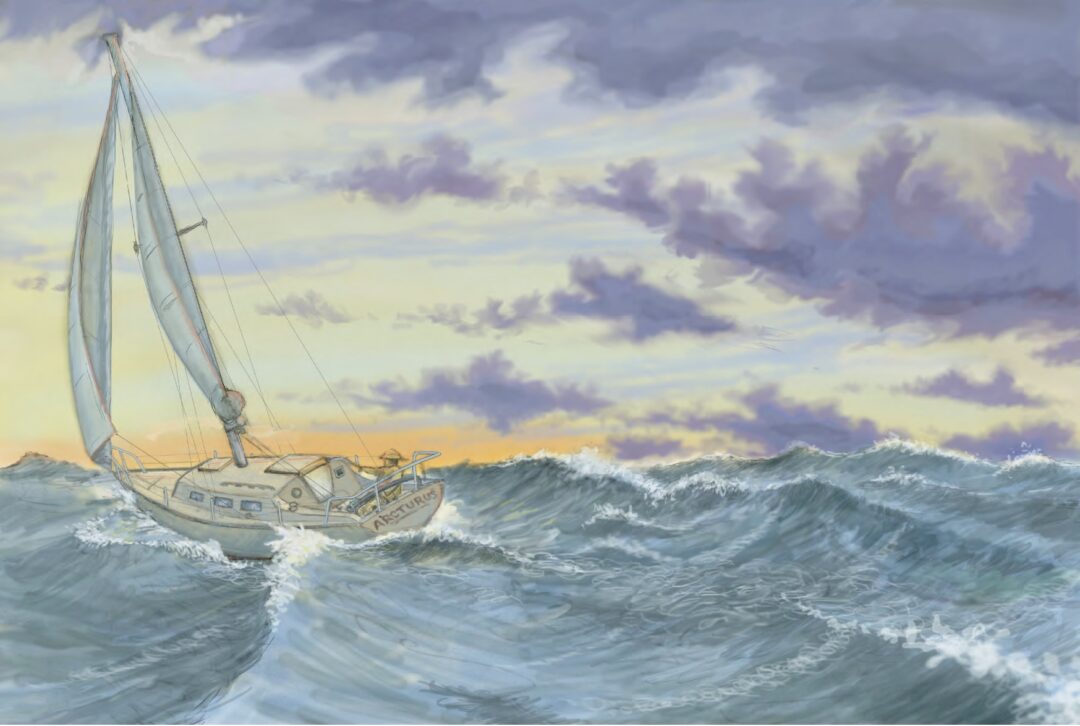

It was only five years ago that we bought our first sailboat, shortly after learning the basics on a friend’s 26-foot ChrisCraft sloop. I suppose it’s somewhat late in life (I’m now 69) for something new to become a defining presence. And maybe that’s the reason— whether I’m reading about sailing, working on Arcturus, our 42-year-old, 27-foot Columbia 8.3, or sailing on Lake Michigan—that I find myself constantly asking: Why? Why do I sail?

One would think it easy to articulate the “why” of something one dedicates so much time to, but it hasn’t been easy. And so, the question has persisted.

I read a lot, both in and out of the sailing genre. I recently finished Mountains of the Mind by Robert Macfarlane, a Scottish hiker, mountain climber, and writer. I don’t know whether Macfarlane has ever stepped aboard a sailboat, but his discussion of human perspectives on mountain wildernesses have helped inform my “why” of sailing.

When I’m sailing, I appreciate the living-on-the-edge feeling that comes from knowing that any false move, poor judgment, perhaps taking that untoward calculated risk, could end in discomfort, or running aground, or even a knockdown. In the mountains, Macfarlane finds the same keen, compelling thrill: “What was simultaneously awful and enthralling about the mountain was how serious even the tiniest error of judgment could be. A slip that might turn an ankle in a city street could in the mountains plunge one fatally into a crevasse or over an edge. Not turning back at the right time didn’t mean being late for dinner; it meant being benighted and freezing to death. On the loss of a glove, a day could pivot from beauty to catastrophe.”

When I’m sailing, I appreciate the living-on-the-edge feeling that comes from knowing that any false move, poor judgment, perhaps taking that untoward calculated risk, could end in discomfort, or running aground, or even a knockdown. In the mountains, Macfarlane finds the same keen, compelling thrill: “What was simultaneously awful and enthralling about the mountain was how serious even the tiniest error of judgment could be. A slip that might turn an ankle in a city street could in the mountains plunge one fatally into a crevasse or over an edge. Not turning back at the right time didn’t mean being late for dinner; it meant being benighted and freezing to death. On the loss of a glove, a day could pivot from beauty to catastrophe.”

Sailing can sate a need for excitement—a tinge of fear and focus—even if it’s just the invisible push as a gust of wind fills the sails, increasing the speed and sending the rail to the surface. Macfarlane gets that, quoting Jean Jacques Rousseau: “I must have torrents, rocks, pines, dead forest, mountains, rugged paths to go up and down, precipices beside me, to frighten me.” When was the last time you welcomed a bit of fear that crept into your time on the water?

Our sailing adventures are what we make of them. Each passage is an open book, our tabula rasa. How we experience the wind and water, the companionship of the galley or cockpit, the rush of swells under the hull, the play of sun and clouds on the horizon, is inevitably a personal product of our imaginations and perspectives.

Macfarlane says so it is with a mountain. “What we call a mountain is thus in fact a collaboration of the physical forms of the world with the imagination of humans—a mountain of the mind. And the way people behave towards mountains has little or nothing to do with the actual objects of rock and ice themselves. Mountains are only contingencies of geology. They do not kill deliberately, nor do they deliberately please: Any emotional properties which they possess are vested in them by human imaginations. Mountains—like deserts, polar tundra, deep oceans, jungles, and all the other wild landscapes that we have romanticized into being—are simply there, and there they remain, their physical structures rearranged gradually over time by the forces of geology and weather, but continuing to exist over and beyond human perceptions of them. But they are also the products of human perception; they have been imagined into existence down the centuries.”

I’ve heard others characterize sailing as a selfish, narcissistic, self-indulgent activity. Macfarlane recognizes this among mountain climbers as well but finds a deeper explanation for this perception: “This is the human paradox of altitude: that it both exalts the individual mind and erases it. Those who travel to mountain tops are half in love with themselves, and half in love with oblivion.”

Each time we cast off the mooring or set a course to cross leagues, we are venturing into the unknown, even when we think we’ve a handle on the conditions we’ll encounter that day or week under sail. Consummate explorer Wilfred Thesiger gives evidence in his biography that this may be a draw in and of itself. “So we…have taken steps to relocate the unknown. We have displaced our concept of it upwards and outwards, on to space—that notoriously final frontier—and inwards and downwards, to the innermost chambers of atom and gene, or the recesses of the human psyche: what George Eliot called ‘the unmapped country within.’ ’’

For those of us who sail in northern climes, during the off season, when the boat is in the cradle, we find ourselves poring over lake and ocean charts, planning next season’s voyages. Macfarlane understands better why I do this than I. “The blank spaces on a map—‘blank spaces for a boy to dream gloriously over’ (Joseph Conrad)—can be filled with whatever promise or dread one wishes to ascribe to them. They are places of infinite possibility. Maps give you seven-league boots—allow you to cover miles in seconds. Using the point of a pencil to trace the line of an intended walk or climb, you can soar over crevasses, leap tall cliff faces at a single bound, and effortlessly ford rivers. On a map the weather is always good, the visibility always perfect. A map offers you the power of perspective over a landscape: reading one is like flying over a country in an aeroplane—a deodorized, pressurized, temperature-controlled survey. Maps do not take account of time, only space.”

And when my voyages are over—particularly when they are solo passages—I find it difficult to express their meaning to others. How can I relate all of the emotions, feelings, sights, sounds, and smells of the trip, the challenge and growth that occurred while I was away? Again, Macfarlane echoes my sentiment in relaying the same about post-climb feelings: “The experiences you have had are largely incommunicable to those who were not there. Returning to daily life after a trip to the mountains, I have often felt as though I were a stranger re-entering my country after years abroad, not yet adjusted to my return, and bearing experiences beyond speech.”

Finally, sailing reminds me that I am usually only partially in control. Despite proper planning, practicing good technique, constantly thinking about safety, appropriate outfitting, control is an illusion.

“At bottom, mountains, like all wildernesses, challenge our complacent conviction—so easy to lapse into—that the world has been made for humans by humans,” Macfarlane writes. “Most of us exist for most of the time in worlds which are humanly arranged, themed, and controlled. One forgets that there are environments which do not respond to the flick of a switch or the twist of a dial, and which have their own rhythms and orders of existence. Mountains correct this amnesia. By speaking of greater forces than we can possibly invoke, and by confronting us with greater spans of time than we can possibly envisage, mountains refute our excessive trust in the man-made. They pose profound questions about our durability and the importance of our schemes. They induce, I suppose, a modesty in us.

“Mountains also reshape our understanding of ourselves, of our own interior landscapes. The remoteness of the mountain world—its harshnesses and its beauties—can provide us with a valuable perspective down on to the most familiar and best charted regions of our lives. It can subtly reorient us and readjust the points from which we take our bearings. In their vastness and in their intricacy, mountains stretch out the individual mind and compress it simultaneously; they make it aware of its own immeasurable acreage and reach and, at the same time, of its own smallness.”

I may never fully understand the “why” of sailing. I suspect Macfarlane may feel the same about his mountains. While deeper understanding is always a worthy effort, sometimes it’s enough to live in wonder, and to be grateful for the source of our wondering.

Gregg Bruff is a retired National Park Service ranger who relocated from Lake Superior to Lake Michigan and the “banana belt.” He and his wife, Mimi, sail a Columbia 8.3 they call Arcturus. Gregg is a landscape painter, writer, avid reader, and enjoys all things outdoors. When not sailing, he enjoys teaching classes and working with students on the high ropes challenge course at Clear Lake Education Center where Mimi is the director.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com