Most everything, according to surveys

Issue 120: May/June 2018

We spent two years preparing our boat to cross the Pacific. We read countless blogs and peppered experienced ocean sailors with questions about what to expect and what kind of preparations to make. We joined a group called the Bluewater Cruising Association and attended the monthly fleet meetings aimed at preparing the upcoming year’s contingent of would-be ocean crossers.

Despite our preparations, and despite our constantly monitoring chafe, things broke. Over the course of the crossing, we had to rebuild the autopilot twice, replace mainsail slides that ripped out, rewire the freshwater pump, and replace the boom vang.

And we got off easy. During our crossing, we escorted another boat for 1,000 miles after it lost the use of its rudder and the gooseneck attaching the boom to the mast broke.

Equipment failures are equipment failures, whether they happen within sight of a harbor or 1,500 miles offshore. Being aware of what’s likely to fail, being equipped to manage when failure occurs, and even being able to prevent some failures, are important to every sailor.

The one thing we wished we had read before we left on the crossing was an account of what the most common major problems are. Everybody told us to take spares for everything, which is a nice idea in theory but nearly impossible in practice. A spare mast? Spare engine? How much spare hose? It’s completely impracticable, short of towing an identical boat behind you, to have spares for everything. So it’s a game of optimization. What are the most common items that break, and what should we have on board to fix or replace them? The sailors who cross oceans are the ones rich in failure experience. I set out to learn as much as I could from their experiences as well as my own.

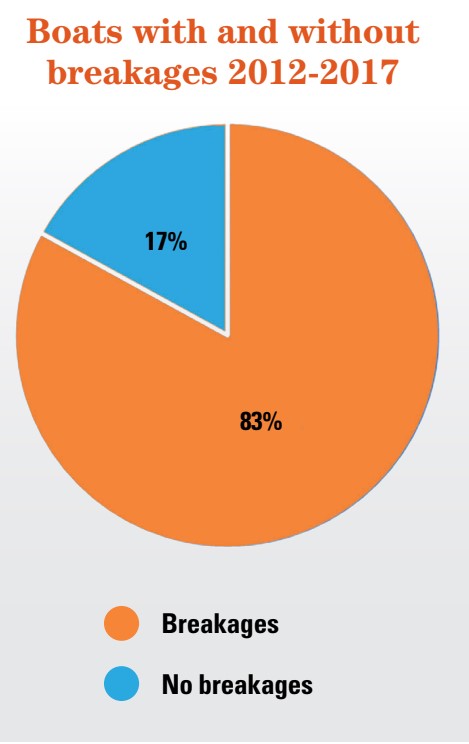

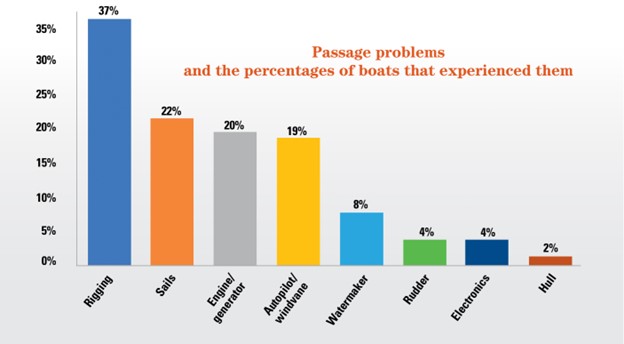

Hundreds of boats cross the Pacific every year, but few report on what they experienced in terms of major gear failure. I’ve put together data from 153 yachts that crossed the Pacific Ocean from 2012 to 2017 to identify the most common major problems experienced during their trips. The data from 2012 to 2016 is self-reported via a questionnaire sent out by Latitude 38 magazine as a part of the Pacific Puddle Jump recap and is publicly available on its website. I personally collected the data for 2017 from fellow Pacific crossers I met in French Polynesian anchorages.

Defining a breakdown

What constitutes a major breakdown is subjective in most cases. Most sailors would consider losing an autopilot a major failure, but a few crews set off on their crossings without an autopilot on board. For the most part, what most consider major malfunctions include anything that adversely affects the functioning of the sails, standing rigging, running rigging, rudder and steering assembly, engine, navigation, electrical generation, water production and storage, autopilot/windvane, and communications.

Overall (83%)

Of the 153 boats that reported data from their Pacific crossings in the last six years (2012-2017), 127 (83 percent) reported major breakdowns. In almost every case, the breakdown was reparable at sea with onboard spares or other equipment. In some cases, the boats limped in to a port where repairs could be made. The lucky few, 26 boats (17 percent), reported no major breakages during their crossings.

Running rigging (34%)

Running rigging tops the list with 52 boats (34 percent) experiencing failures during the Pacific crossing. Chief among these is halyard failure, usually the result of either main or spinnaker halyards chafing through or shackles breaking. There were no reports of jib halyards chafing through, or shackles breaking, though 5 boats (4 percent) did report headsail-furler failures. Reefing lines, because they are difficult to tension when not in use, also caused a lot of chafe on other lines, or chafed through themselves. The rest of the running rigging failures were spread over boom vangs (7 boats), preventers (3 boats), and travelers (3 boats).

Standing rigging (3%)

Four boats (3 percent) had problems with standing rigging. A shroud toggle broke on SV Kokomo, while SV Ladoga noticed, during a regular rigging inspection, that a lower shroud was unwinding from being slack on the lee side for more than two weeks. The most serious case saw both lower diagonal shrouds, D1s, on SV Fandango detach from the mast after the through-bolt holding them broke. The crew of three, Ian, Brad, and Liz, were able to rig a Spectra line around the lower spreaders to keep the mast in column and prevent it from buckling. They continued sailing for another 1,500 nautical miles before they were able to make proper repairs. In all cases of major rigging failure, the rigging was older than 10 years.

Sails (22%)

More than 34 boats (22 percent), including us, had to deal with torn sails. The sail failures reported most often were blown spinnakers, followed by a torn mainsail. In one case, the poor crew aboard their 48-foot catamaran, SV Kiapa Nui, “ground” a tear into their mainsail by over-tightening the mainsheet with the winch. We had a sail slide break out of the mast on day two as a result of the boom slatting back and forth in light winds. Our genoa also began to tear at the tack and we were required to stitch a patch into it under way. Both sails were only two years old and were made by Neil Pryde, a reputable manufacturer.

Sail chafe is a sailor’s constant adversary whether sailing offshore or going out for the day. John, aboard SV Jandamarra, whom we met in the Marquesas, recommended that we take 15 minutes a day when we’re under sail to walk around the deck and inspect the sails, halyards, and rigging for signs of chafe or material fatigue. Since we employed his advice, we have discovered many small defects and have been able to preempt some major problems.

Engine issues (20%)

Engine problems, especially polluted fuel, malfunctioning alternators, and over-heating, affected 31 boats (20 percent). The constant motion can cause debris in the fuel tank to clog the filter and/or injectors. More commonly, water gets into the fuel tank, either through bad fuel at the dock, condensation, or back-siphoning through the fuel-tank vents.

Alternators failed at a surprisingly high rate, with 11 boats (7 percent) reporting problems. One reason might be having to make up for the increased power demands on the batteries due to day/night sailing by running the engine at relatively low rpm to recharge them. In most cases, boats had spare alternators on board that they could swap in.

SV Shakedown, on the 2017 crossing, lost her diesel generator and engine. For most of their 48-day crossing, the crew used solar and their Honda 2000 suitcase generator, with only 3 gallons of gas, to keep pumps operating, lights on, and the Iridium GO! charged. They navigated by handheld GPS and hand-steered 3,000 miles to French Polynesia. (Their epic story is posted at sailshakedown.blogspot.com.)

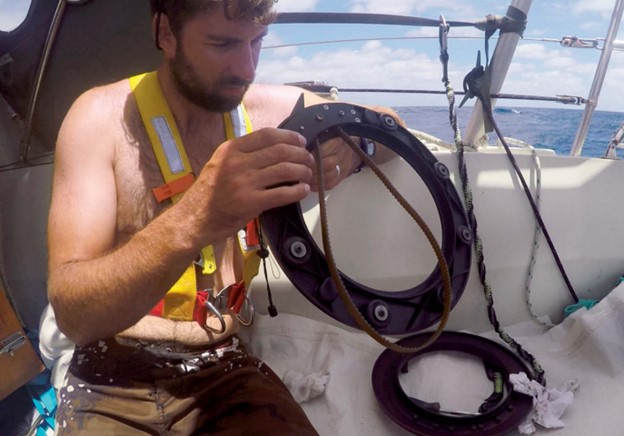

Autopilot and windvane (19%)

Most offshore sailors now consider autopilots essential gear, which is why it’s no joke when 14 percent of boats have major autopilot failures. Twice on the crossing we had to rebuild our autopilot, for which we thankfully had spare belts. Our friend Rob on SV Tigerbeetle, an older Morgan IOR 2 Ton race boat, had to repair his three times and went through two hydraulic rams on his crossing this year. He still made the 3,000-nautical-mile crossing in 19 days. Only seven boats (5 percent) reported windvane failures. It is still a good idea to have spares or a rebuild kit on board for the windvane.

Watermaker (8%)

Watermakers aren’t a big concern for non-cruising boats and few even have them, but on an ocean crossing they can mean the difference literally between life and death. We had a scare five days out where our watermaker started producing foul-tasting water. We didn’t have enough water stored on board to last the whole trip and we got nervous. Thankfully, we were able to overcome the problem by simply replacing the pre-filter and running some pickling solution through the system. However, 12 boats (8 percent) had major failures that rendered their watermakers inoperable.

The crew on MV Idlewild, a custom-built Reyse 54, resorted to catching rainwater in squalls and used seawater for everything except drinking and brushing teeth after their watermaker stopped working.

Hull (2%)

Interestingly, no issues were reported involving keels and only two with failed through-hulls. In 2017, on the catamaran SV Le Chat Beaute, an emergency hatch broke free, leaving a 2 x 2-foot hole in the hull. With quick thinking, cushions, and plywood, they stanched the leak and were able to sail the three days back to La Cruz. (Apparently not reported was the 2015 abandonment of the S&S 42 Nirvana Now, after the hull and deck separated at the bow. –Eds.)

Whether making long passages or short, it makes sense to have a plan for dealing with major hull breaches.

Rudder (4%)

Rudder failure is a major problem on any boat. We escorted SV Rosinante for 1,000 miles after she experienced major rudder issues. After we got in to the Marquesas, two more boats showed up with rudder failures. Of the 153 boats that reported, only six had major problems with their rudders. This issue is about as serious as it gets, and it behooves us to have at least a plan in place should we lose the rudder. The best-case scenario is to carry a spare rudder (remember to try it in a real swell), but failing that, it is necessary to have knowledge of and practice configurations for drogue-style rudders.

Electronics (4%)

A few boats (4 percent) reported communication and GPS/chart-plotter issues, which seems quite low. A likely reason for this low number is the redundancy built into the navigational systems of most offshore boats these days; the function of one failed system can usually be taken up by another and often is not considered a major problem. Our SSB/Pactor system failed two days out of Mexico and we had to return to fix it. While there, we bought an Iridium GO! to provide redundancy. A couple of boats that reported GPS/chart-plotter issues simply overcame the problem by changing to another GPS system. Most boats carry at least large-scale admiralty charts of the areas in which they’ll be cruising, in case of total electronic failure.

Minor malfunctions (15%)

Unfortunately, 16 boats (10 percent) had plumbing issues, usually involving the macerator pump for the head. Another 8 boats (5 percent) broke their whisker poles, the most common cause being a rapid change in wind direction accompanying a squall. One boat lost its primary anchor to a large wave.

Just plain weird (1%)

Sometimes, things happen to boats that can’t be predicted — the so-called “one percent.” In 2017, the propeller shaft on the Deerfoot 60 SV Just Passing Wind decoupled from the engine. They stopped the flow of water from the now-empty stern tube, but thought they had lost the shaft and propeller altogether. Days later, when they dropped anchor in the Marquesas, they dove under for a look and found the end of the shaft miraculously hanging from the Cutless bearing.

Preventive maintenance

Through careful observation, regular checks, and scheduled maintenance so many problems can be avoided or at least minimized. Few failures occur without a warning of some kind. An alternator-belt failure may be merely an inconvenience if a spare is carried aboard, but it is only a scheduled maintenance item if replaced before it fails.

The boats that had no major breakages all talked about their rigorous preventive maintenance. But this kind of vigilance can only go so far. Eventually, something unseen or unseeable will break, and when this happens you need the right parts and tools on board to deal with it.

There are few feelings better than quickly and efficiently managing a major malfunction at sea, and there are few feelings worse than not being able to. While maintenance is the most important step that can be taken to prevent breakages, at some point something is going to break. By knowing what the most common failures are, you can take measures to defend yourself against many of the otherwise inevitable breakages.

MonArk’s passagemaking spares

It is simply not practical to carry spares for every item on the boat. However, it is a good idea to keep your boat well stocked with spares or materials that will come in handy for the more common issues. Every boat and sailor is different, and it is up to everyone to make a list of spares they might need for their boat and where they sail.

Based on our own experience and the experiences of other Pacific crossers, I’ve come up with the following list of 18 spares I aim to keep on board to manage the most common issues.

• Sail-repair kit and extra sailcloth

• Mainsail slides

• Spare sails

• Replacement halyard line and a bunch of extra snapshackles and regular shackles

• A few hundred feet of nylon or polyester line in various diameters

• A few hundred feet of Spectra with a block-and-tackle tensioning system

• Spare alternator(s)

• Spare V-belts or serpentine belts

• Engine (and generator) raw-water-pump rebuild kit

• Baja filter or other fuel/water separator

• Many spare Racor fuel filters

• Autopilot rebuild kit and/or spare autopilot

• Windvane rebuild kit

• Watermaker pre-filter spares and spare membrane

• Watermaker pump rebuild kit

• Man-overboard drogue or similar for making emergency steering device

• Backup GPS

• Large-scale admiralty charts of the cruising area

Del Viento’s Pacific experience — Michael Robertson

My wife, our two daughters, and I crossed from Mexico to the Marquesas in April/May 2015, so our 26-day crossing experience aboard our 1978 Fuji 40 is reflected in Robin’s data set. We were among the lucky ones who experienced no significant breakages. In fact, the only problem we faced — despite enduring a 400-mile-wide ITCZ filled with squally weather and then some hard-on-the-wind sailing from the equator to Fatu Hiva — was the parting of a section of the protective strip of Sunbrella from our furling headsail. We simply took down the sail en route and taped and stitched a repair by hand, down below. I don’t credit our success to better preparedness as much as to luck. Preparation is key, but I know firsthand that at least some of the boats that experienced major failures prepped as carefully as we did. Sometimes, it’s just your turn, and it’s important that you be ready for that.

Crisis or inconvenience? — Jeremy McGeary

It’s been a long time since I crossed an ocean or made an offshore passage of any kind, so some of the “breakdowns” Robin describes made me chuckle.

Autopilots were not common when I began my career, nor were they robust. They were OK for motoring in calm seas but could not cope under sail in much wind or sea. So we’d ship a couple of extra hands and steer the boat — and get an aerobic workout before the term was even invented. Today’s powerful autopilots are a direct result of the singlehanded around-the-world races, where sailors need a reliable hand on the helm 24/7. And still everyone has to carry a spare . . .

Watermakers were not yet available, at least not at price or scale for the average cruising boat. We filled the tanks before departure and watched every drop of fresh water consumed. And we switched off the pressure pump, if the boat was so equipped. If we were foolish enough to run out, we’d have to look for some rain clouds to chase. Showers? Pah! A saltwater bucket bath was good enough; a rain-shower was a luxury.

Electronic navigation systems did not exist, never mind redundant ones. We used a good old lightning-proof sextant, a hand-bearing compass, a few books, lots of charts, and the Mk I eyeball.

Communications were pretty much nonexistent once we left port (and not much better in port). In the 1970s, the standard radio equipment was AM, with a range of maybe 200 to 300 miles. I don’t recall being on a boat with an SSB radio. When we got to the other side of the ocean, I would write a letter to Mum.

Macerator pumps are usually associated with holding tanks and/or electric heads . . . but using a holding tank is not necessary when at sea. Some yawls had a rudimentary thunderbox — a toilet seat fastened to the boomkin. And there’s always the ever-ready bucket. Privacy is but a memory after a couple of days at sea.

Robin Urquhart’s master’s degree in building engineering has been severely tested since he and his partner, now wife, Fiona McGlynn, headed south from Vancouver, and then west from Mexico, on MonArk, their good old 1979 Dufour 35. Check out their blog at www.youngandsalty.com, where they reach out to younger sailors who share a passion for good old boats.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com