Oxford’s Downes Curtis was one of Maryland’s most enduring sailmakers.

Issue 147: Nov/Dec 2022

Maryland’s deep maritime heritage is inextricably linked to the stories and experiences of Black people on the Chesapeake Bay. As an enslaved boy, Frederick Douglass began to learn to read and write while spending time in Durgin and Bailey’s shipyard in Baltimore, where he watched shipwrights mark each piece of timber with a letter indicating its location in the ship’s construction. Later, he worked as a caulker for Fells Point shipbuilder William Gardner, and he used those skills to get a foot in the door on the wharves in New Bedford, Massachusetts, when he fled Maryland and slavery in 1838.

It’s likely that free and enslaved Black Marylanders worked in the lofts supporting the fleets of sail-powered vessels that dominated Bay commerce until well into the early 20th century. But one of the only full-time, independent Black sailmakers in the state through the 1900s, and certainly the most enduring, was Downes Curtis of Oxford, Maryland. He and his younger brother, Albert, learned the craft from Dave Pritchett, an English sailmaker who had come to the Eastern Shore town on the Tred Avon River. When Pritchett died in 1936, Downes and Albert continued the work of the sail loft.

“We cut canvas sails for log canoes and oyster-dredging boats, you know, skipjacks and bugeyes,” Curtis told Jack Sherwood in Maryland’s Vanishing Lives. “If they didn’t get sails from us, they got them from Mr. Brown in Deal Island. Mr. Brown is gone. Only us is left who do it the old-timey way.”

at the loft in Oxford. By H. Robins

Hollyday. Photograph from the collection of the

Talbot Historical Society.

According to Sherwood, the brothers also cut sails for their oysterman father, Raphael, as well as for recreational yachtsmen who brought their boats to one of Oxford’s many boatyards. A 2001 story in the Easton Star-Democrat noted that the brothers made sails for the likes of Errol Flynn, James Cagney, Walter Cronkite, and the Kennedy family, among others.

The loft building itself was once a school for African American children up to grade eight, Agnes Washington, Curtis’ sister, told the Easton newspaper.

from the collection of the Talbot Historical Society.

“All nine Curtis children attended classes at the schoolhouse where our mother had been a teacher,” she said. Today, the loft building is a private residence. The owner told a local news crew she still finds hooks and nails from when the Curtis brothers stretched sails across the floor.

Locally, Curtis became best known for his craftsmanship in building sails for traditional log canoes. Once used for commercial fishing and oystering, low-slung log canoes now are used only for racing on the Chesapeake, with the fleet based on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Like other commercial boats of the time, speed to market was of the essence, and log canoes—their open hulls loaded with oysters for ballast—carried clouds of sail to propel them. Today, the clouds of sail remain, but the ballast is human–crews who hike out on boards called prys to keep the over-canvassed, tender boats from capsizing.

Curtis became a renowned log canoe sailmaker and cut sails for some of the most competitive and historic boats in the fleet. His skills were such that they were noted by historians who sought to place the log canoe Island Blossom on the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1892 in Tilghman Island, Island Blossom is now owned by Judge John North of St. Michaels, and the Maryland Historical Trust’s National Register Properties listing notes that, “The sails were cut by Downes Curtis of Oxford.”

Curtis continued to make sails in his loft until his death in 1996 at age 85. In 2015, the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum (CBMM) launched an exhibition featuring his tools and sailmaker’s bench. The museum’s magazine, The Weather Gauge, noted in a 1997 story that Curtis “stands out as an African-American maritime artisan on the Chesapeake Bay.”

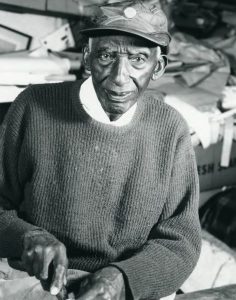

Downes Curtis, from the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum exhibit that included some of

the sailmaker’s equipment and tools. Photo, David W. Harp, Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum Collection (1997.1.117).

This story originally appeared in Maryland Sea Grant’s magazine, Chesapeake Quarterly: Black on the Bay, Then and Now, Vol. 20, No. 1, February 2021. Access the magazine and the story’s digital version at chesapeakequarterly. net/V20N1

Good Old Boat Senior Editor Wendy Mitman Clarke is also a science writer and editor at Maryland Sea Grant. You can see more of her work at wendymitmanclarke.com

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com