What started as a much-needed refit devolved into a scary search for mangy metal.

Issue 138: May/June 2021

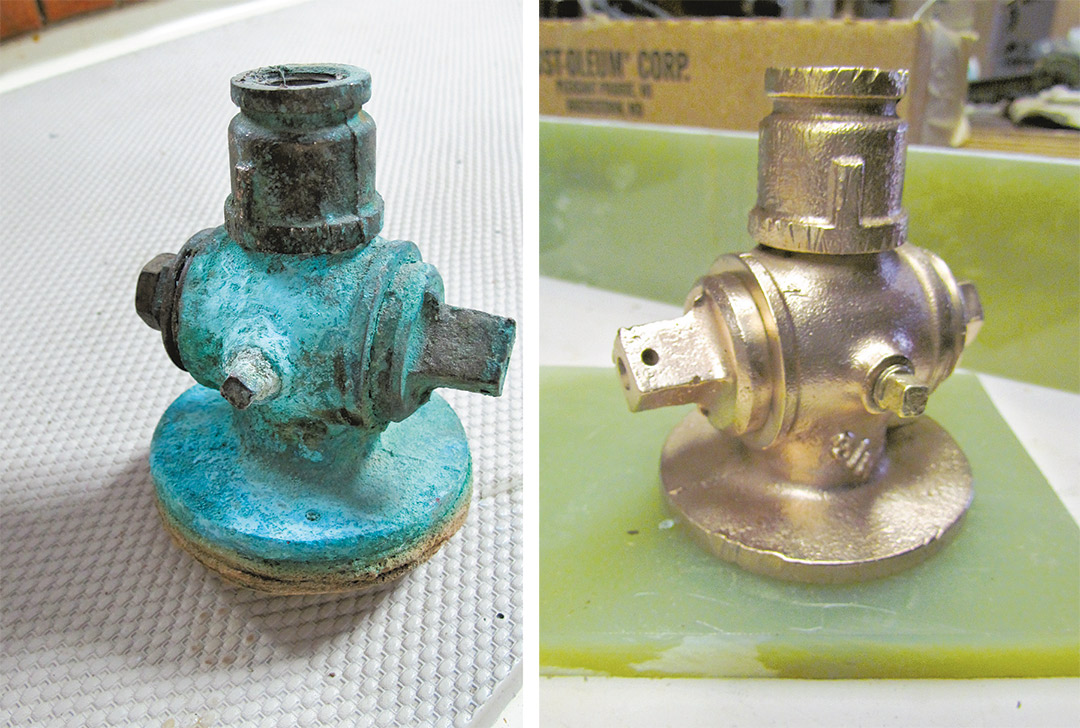

It all began with a corroded ball valve. It was seized, which rendered inoperable the seacock it was a part of. After 14 years of full-time voyaging, our homecoming fun on the Chesapeake Bay was cut short by one important failed valve. We immediately arranged for a haulout (“Battling with Ball Valves” January/February 2018).

Even then, the plan was to quickly replace the valve and carry on. But hang on a minute, what’s the hurry? This was an opportunity to take a good hard look around, and we didn’t like what we saw. Despite all the love and meticulous maintenance we’d always showered on our beloved Entr’acte, she looked…shopworn! Years of African and tropical sands had settled behind the interior woodwork, and her galley reminded us of a kitchen in a restaurant we would avoid. Entr’acte looked great from 50 feet away, but if we got up close and realistic, she had turned into one more tired old cruising boat that had gone on far too long.

This boat had always received the best that we could give her…under the circumstances. When voyaging afar, no matter how good your intentions, projects can seldom be completed to the same standard they would be at home. As the miles accumulate and the years take their inevitable toll, things get ahead of you. It was time for us to stop and move ashore to do them right.

Entr’acte, a Nor’Sea 27, was conceived as a trailerable ocean-capable vessel. We’d built her in our backyard from a bare hull sitting atop a trailer. Fortunately, we remembered where we’d left that trailer 14 years before, tucked away on a Chesapeake Bay farm. A plan took shape: trailer Entr’acte back to our Arizona home where we had the facilities to tackle any project that needed tackling.

After a week on the road, we were home, and the first order of business was unloading our boat—quite literally. Our dream to permanently remove 1,000 pounds of excess weight was finally coming to pass.

Every single item that was not permanently attached we removed, catalogued, weighed, and stowed in a cargo trailer. We knew that some items would eventually be reloaded, but most, happily, would not.

Off came the wind and water generators along with all of their respective spares. Next came the spare alternator, voltage regulator(s), spare piston and connecting rod, valves, springs, and enough bilge pump rebuild kits to start our own chandlery. There were spares for the spares of spares and then a few spares for those as well. Seven GPS wiring harnesses, five more for the two autopilots, and enough spare parts to rebuild our Aires vane gear three times over. There were spare chainplates, rigging wire, mast fittings spares, outboard engine spares.

“What’s all that in the back of my car?”

“Boat stuff, but the good news is that the forward number two locker is empty.”

“So, the bad news is that it’s all in my car?”

“Yes, but, the good news is that none of this is going back and it weighs in at 84 pounds!”

By week’s end and after some sorting, we had forever removed 750 pounds from a 27-foot boat, and this was just the beginning. Completely unloaded, we could now see and access everything. Ellen began cleaning while I tackled the boom gallows.

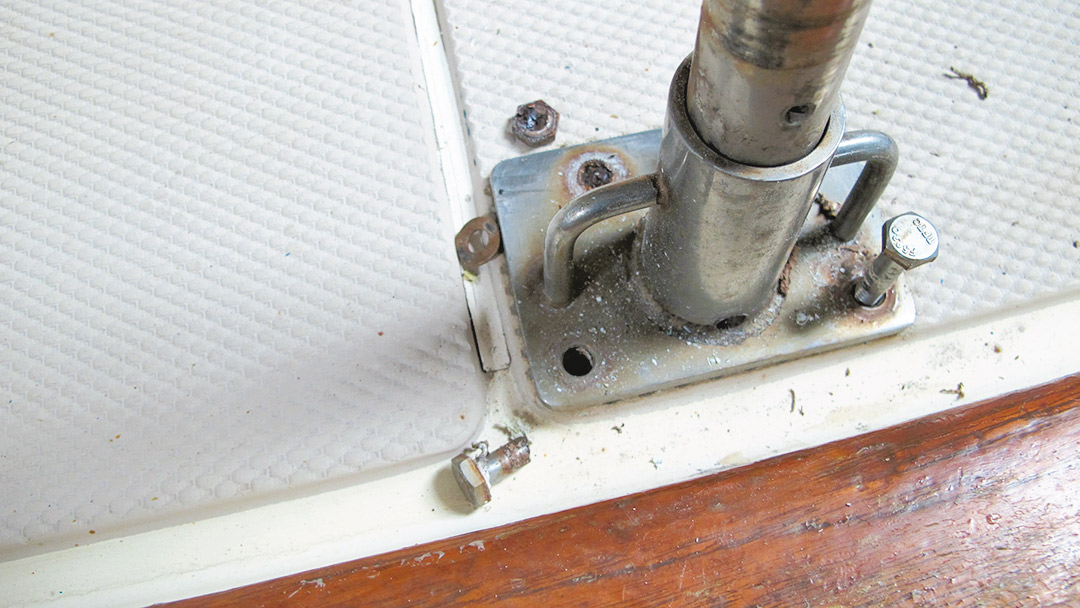

A boom gallows works a lot more than one might expect. Its fastenings experience constant torsion and flexing whether at sea or at anchor. We lean against it while underway, we stand on it, fall against it, and pull on it when boarding. With the boom lashed down in a seaway, the motion of the boat and boom impart constant side loads on the fastenings. Each tug, twist, bend, shock, or stretch constitutes a cycle. These mounting bolts had been cycling constantly over the years, and this simple job was at the top of my to-do-it-right list.

I set a socket and wrench over the center nut, and before I could apply any force at all, the head of the 3/8-inch stainless steel bolt snapped off. Of the four remaining bolts, two were intact while the other two were corroded through. The same thing happened on the starboard side. The bedding compound, now 40 years old, was dried out and mostly nonexistent, a clear explanation for the corroded bolts.

I felt a vague disquiet. Entr’acte was sending us an unambiguous message.

When we built her back in the 1970s, we used the finest materials and construction methods then available. Over the years, she has sailed countless miles and has undergone several re-riggings and two complete refits with appropriate surveys that resulted not only in updated gear, but also addressed and corrected a few original sins. This present endeavor was, however, shaping up to be something completely different.

It was time to dig in, and our focus was metal.

For the next several months, Ellen and I worked 12-hour days as though possessed. We started at the stern and moved forward, systematically and completely disassembling our boat. We removed anything that was screwed or bolted down. We looked everywhere for trouble and found it, most of it buried and out of sight.

We exempted the chainplates, rig, and engine from scrutiny because all had been completely redone within the past four years. We spared ourselves the massive project of removing the teak cap rail after conducting an extremely close, inch-by-inch, fastener-by-fastener inspection that showed the cap rail screws, scarf joints, and underlying bedding compound to be completely sound and leak free. We inspected each of the hull-to-deck joint bolts with a magnifying glass, knocked, shook, and twisted. We breathed a sigh of relief to find them as solid as the day they were installed. The hull-to-deck joint itself showed absolutely no sign of shifting or leaking, which, after so many years and miles, was impressive and welcome.

However, this is where the buggy ride ended.

Preparing for the remounting of the gallows frame, I noticed some green coming from a mounting bolt of the bronze portlight immediately adjacent to the gallows frame. A closer inspection revealed the beginning of a leak originating from this bolt and the one next to it. The port would have to be reinstalled. I felt the soft “snap” as the first of two of the six silicone bronze mounting bolts broke off. All of the damage was internal and well hidden.

Too many of the fasteners we removed elsewhere were ghastly and gave us chills. Our days became a litany of metal deterioration. Not every fastener was bad and broken, but enough fit that description to warn us that if we replaced only the bad ones, more failures were in our future. So, without further exception, we replaced every fastener and hose clamp.

While building Entr’acte, we bought fasteners in boxes of 100. When a job required one box, we bought three. If we needed three boxes, we bought six. We’d stored the excess hardware at home for later use, as a hedge against inflation. Now it was paying off. The current prices of the fasteners we did have to buy stunned us.

Every day we discovered some new evil, deeply hidden, that could have easily, justifiably failed during our most recent ocean crossing, and with likely catastrophic results, such as the loss of the vessel or one of her crew.

A thought occurred to me and I swallowed hard. You’ve seen these words a hundred times:

“This vessel has been lovingly and meticulously maintained and is turn-key ready to sail anywhere your heart desires!”

It’s what I’d have written a month before were we selling Entr’acte—and I’d have meant it, sincerely, with complete confidence and without reservation. Yet seeing only the hidden corrosion I’d uncovered so far, knowing there was much more, I’d have been dead wrong attesting to my boat’s readiness to put to sea. It was a sobering thought.

The grabrails were a real eye-opener. Each aft cabin rail was through-bolted with three silicone bronze bolts. Only one bolt out of three on each side was intact. My mind flashed back to Fiji where a sudden squall had knocked us flat. As the mast hit the water, I grabbed that handhold in a desperate attempt to haul myself upright. Had that one final bolt let go at that time, I’d have fallen straight through the lifelines and not be writing this article.

The main cabin rails were no better. Each was attached with 13 bolts, and five bolts on each side were broken internally. My theory is that the corrosion resulted from condensation that was trapped for years in a no-oxygen environment, leading to a gradual deterioration. Coupled with constant loading of the fasteners of the stanchions, handrails, and fittings while underway, this caused work-hardening and eventual failure.

But none of this was apparent until we disassembled everything.

Then there were the stanchions that we rely on to keep us aboard. Cracked bases, visible upon close inspection, indicated that these might have failed under the load of someone falling against them.

Our stainless steel holding tank could best be described by paraphrasing Captain & Tennille: “Rust. Rust will keep us together.” I removed the tank only to clean it up with a wire brush, but as the brush whirled around, chunks of the tank fell away, and I knew then that I am not a person who should ever have a metal hull.

The prop shaft was another matter. In the beginning, we used the standard stuffing box and flax packing gland to keep out seawater. When adjusted properly, the gland dripped a scant few drops of seawater per hour into the bilge, and this controlled water flow lubricated and cooled the shaft.

But this gland is also a source of friction, and if tightened too much, severe damage can result. We were at peace with our packing gland until we repowered years ago. The new engine used “improved, softer” motor mounts, and from then on it either leaked too much or the shaft became too hot. I was always fiddling and trying miracle lubricants, but it was never right.

After we noticed a wear spot from those years of friction, we gave up on the packing gland and installed a PYI dripless shaft seal, which mounted well clear of the worn area. The leaking, friction, and heat stopped immediately, and we never looked back. This was a mistake. And so, we were only seeing now that as the years passed, the shaft developed pitting and a small crack in the damaged, worn area.

This refit had taken a decidedly different form from our plan, and we spent many evenings berating ourselves for our gross negligence. Yet, consider that Entr’acte has undergone seven professional surveys over the years and passed them all with flying colors. Two of these surveys were unrelenting and brutal. But none of them revealed, or could have revealed, what we found through extensive disassembly.

As bad as much of the original bedding compound appeared—and it was certainly a factor in many of our out-of-sight corrosion issues—the absence of leaks and core deterioration proved that it had done its job quite well. We’d strategically used specific sealants for specific applications, and this was successful, though complex (see sidebar for more on sealants).

What have we learned?

- It’s a boat, and being assured of its integrity requires digging into places where no one really wants to go. Regular maintenance is a given, but we must go further and while it’s downright inconvenient and time-consuming, it’s critical.

- Regardless of quality, no fastening, fitting, wire, glue, or bedding compound lasts forever. We all know these good old boats are tough enough to last lifetimes, but we aren’t sailing empty pieces of fiberglass; we’re sailing craft assembled with wood and compounds and different types of metals.

- Every fastener on the boat is constantly cycling, even when nobody is aboard, which wears and damages over time. Every time the boat rolls and you brace your foot against a rail, stanchion, or fitting, that imparts one more cycle as the fitting and fastenings absorb the force you impart.

- Grabrails work harder than we think. We stand on those rails, walk on them, use them for foot support in a seaway. Dinghies, solar panels, and other gear are tied to them.

- Dock and anchor cleats are similarly abused. Every time the boat moves and is restrained, the cleats and the bolts that secure them are stretching and flexing as they withstand forces. And in a blow, the strains are magnified.

- Make note of which fastenings are being asked to work more than others and target them for closer inspection. Bear in mind that not all fastenings deteriorate at the same rate. Out of 15 bolts taken from the same box, 10 will last for 40 years while five may have to be replaced after five years.

- Metal degrades and weakens for reasons that range from poor quality to friction, wear, flexing, impact, electrolysis, galvanic corrosion, or crevice corrosion.

- Bedding compound deteriorates from age but also from constant attack by cleaning agents and acids that we use to clean our hulls and decks. These chemicals run along the glass, contact a fitting, and dissolve its bedding compound. No harm is done today but over time the bedding is eaten away, and the insidious consequent damage begins.

- The absence of a leak is no real indicator of the integrity of a fastener. A leak might give some warning, but trapped condensation lurking deep inside where no one can ever see is far more detrimental and dangerous.

Good Old Boat Contributing Editor Ed Zacko, and his wife, Ellen, built their Nor’Sea 27, Entr’acte, from a bare hull, and since 1980 have made four transatlantic and one transpacific crossing. Ed, the drummer, and Ellen, the violinist, met in the orchestra pit of a Broadway musical. While refitting Entr’acte, they have kept up a busy concert schedule in the Southwest U.S. They recently completed their latest project, a children’s book, The Adventures of Mike the Moose: The Boys Find the World.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com