The case for a well that encloses the tilted-up motor

Issue 122: Sept/Oct 2018

Sailboat auxiliary engines, inboard and outboard, have their strong points and weak points, friends and foes. My experiences with both kinds, on my boat and on other people’s boats, has led me to favor the outboard as being far simpler to install and maintain. The outboard’s principal disadvantage, though, is its location, whether it’s hung on a transom bracket or fitted in a well in the cockpit. Over the years, I’ve worked to develop a more convenient way to mount and operate an outboard by installing it in a well that allows it to be tilted up when it’s not in use.

Most cruising sailors are not going to switch from a diesel inboard to an outboard-well conversion. However, if you don’t have unrealistic expectations and are looking for an alternative way to bring back to life a suitable older classic sailboat, the improved outboard well is worth considering. Many worthy old boats languish neglected in forgotten corners of boatyards because they have a blown or ancient inboard engine. Adopting the outboard well might allow some of them to be rescued from the scrapyard.

My 28-foot Pearson Triton, Atom, was originally equipped with a finicky Atomic 4 gasoline inboard that so disliked the salty marine environment and my inept care that it too often refused to do its job. I lived for several years with oil dripping into the bilge and the odor of gasoline permeating the cabin. The final insult came when it spit fire in my face as I knelt before its backfiring carburetor. Our breakup was inevitable.

After my first circumnavigation in the 1980s, I felt I had the seamanship skills needed for the challenge of sailing engineless, so I removed the burdensome beast and sailed across the Caribbean and the Pacific in the rewarding pursuit of purely sail-powered passagemaking. Despite the success of these engineless passages, I came to understand the very real limitations of engine-free sailing, one of which was the number of ports I could not safely enter or exit under sail or sculling oar alone. After a near shipwreck on a wave-lashed rocky coast, and then a terrifyingly close encounter with a tug and barge when becalmed one night in the Sulu Sea, I knew that the long odds of this high-risk game would probably catch up to me one day.

Eventually, I hung a 3-horsepower outboard motor on an adjustable transom bracket. Even then, I relied on my sailing skills and used the motor sparingly, as its limited power could move my 4-ton boat against only the lightest winds and currents and its short shaft meant the prop sucked air in even small waves.

On returning to the US from my second circumnavigation, I upgraded to a 6-horsepower four-stroke 20-inch long-shaft motor, which I attached to a custom transom bracket on twin vertical tracks that let me lift the motor 18 inches for storage at sea. That setup gave me adequate power to stem the currents of the Intracoastal Waterway and ocean inlets, but steering the boat was awkward whenever I had to reach over the transom to operate the shifter and throttle. In its stored position, the motor was unsightly, and its weight was higher and farther aft than ideal for optimal sailing performance.

A better solution

Over the years, I experimented with different outboard-well designs on a variety of boats, and 19 years ago, I built my first seagoing outboard well in a friend’s Taipan 28 sloop (see “The Inside Outboard,” November 2002). That outboard well consisted of a circular hole above the water on the hull’s centerline surrounded with a plywood and fiberglass box. When not being used, the 5-horsepower motor was lifted out of the box and stored on its side in a cockpit locker, and a sealed lid secured to the box to prevent water from entering the locker. My wife, Mei, and I successfully sailed that Taipan on an expanded Atlantic-circle delivery and cruise that took us from the Caribbean to Bermuda, the Azores, Cape Verde, and Brazil. Along the way, the outboard well proved to be a workable system and a huge improvement over the transom bracket.

Effective as that system was, I felt there had to be an easier method of dealing with the motor when going from motoring to sailing, as left in place, it added drag while sailing and risked getting corroded or fouled with growth while sitting at anchor. It was not too difficult to lift out the smaller and lighter two-stroke motors for storage or put them back in the well when it came time to enter port, but those motors were dirty and their use today is restricted by environmental regulations. When I switched to heavier four-stroke motors, I found it impractical to lift them in and out of the locker when under way, and they needed to be stowed carefully to prevent crankcase oil from going places it shouldn’t inside the motor. The longer 25-inch shaft length needed to optimize performance made removing the engine for storage even less feasible.

Elements of the outboard well

Over the years, my outboard-well designs have evolved. It became obvious to me that the ideal solution was a motor that stayed permanently in the well and tilted up through a narrow slot in the transom for storage. I built these improved versions on different models of sailboats, including three Pearson Tritons, a Tripp 29, and four Alberg 30s, among others. On most of those boats, and on two of the Alberg 30s, I installed a 6-horsepower Tohatsu SailPro with a 25-inch extralong shaft and high-thrust prop, because the motor was a good compromise between weight, physical dimensions, and thrust. Most sailors who are used to having more powerful engines consider 6 horsepower insufficient on this size of boat. It’s true you can’t motor into strong winds and waves with 6 horsepower, but many sailors understand the trade-offs of going to higher horsepower and choose not to. The owner of the third Alberg 30 I converted was keen to have more power, and I was able to modify the design to fit a Nissan 9.8.

Whereas the Alberg 30 has a generous lazarette of 34 inches fore and aft that can easily contain an enclosed outboard well, the Pearson Triton presented more of a challenge because of its smaller lazarette. My first outboard well in a Triton was an open-faced design, and the motor head overhung the rudder cap and tiller slightly when tilted up. Even though this design worked and was easy to construct, it did have drawbacks, such as the motor’s intrusion into the cockpit footwell when tilted and more noise and vibration to live with while seated in the cockpit.

An open-faced well seemed less ideal than an enclosed well because the increased volume of the cockpit footwell combined with the open lazarette makes getting pooped by a rogue wave more of a concern. On the other hand, the open well contains buoyancy chambers and it permits faster drainage of the footwell, so I doubt it will ever be much of an issue. On later Tritons, I pushed the motor aft another 1.5 inches and added structural stiffeners to what little remained of the aft deck and the transom above the motor-shaft slot. This modification allowed me to enclose the front of the well while maintaining adequate structural integrity.

In 2014, I figured out how to enclose a 6-horsepower Tohatsu SailPro on Atom by moving the center of the original lazarette bulkhead forward. It was considerably more work than an openwell design, and it required pushing the motor-mount position farther aft and 1 inch higher than on earlier Triton conversions, resulting in a higher and more unsightly raised lid. Even so, I’m happy with the result, and the motor-box lid serves as a good elevated seat or table. The motor pushes the Triton at 5.8 knots at full throttle in calm seas and is surprisingly good when punching into a light headwind and chop.

Boatbuilder options

A functional outboard-well design needs the following: sufficient prop depth to get a bite in moderate waves, a practical way to close off the hull and transom slot at sea, enough clearance from the hull cutout to the waterline to reduce back-flooding, and the largest possible buoyancy chambers built in to the lower portions of the well. If any builders produced a sensible offshore-suitable boat with this type of enclosed tilt-up outboard well, I am unaware of them. Perhaps readers can inform us if they did.

Boats with fixed motor wells as options, such as the Cape Dory 25 and 26, Pearson Ariel 26, and Bristol 27, for example, were popular daysailers, but were not attractive to most potential small-boat voyagers. This was partly because the motors are fixed in place, causing drag turbulence under sail, fouling, and corrosion problems. To my eye, those designs are impractical, except perhaps if the boats are kept on freshwater lakes.

Most problems associated with old-style fixed outboard wells can be avoided if, among other design details, a slot is cut in the hull to allow the motor to tilt up and forward. An added benefit to this approach is that the hull shaft hole and transom slot can be surprisingly narrow and inconspicuous. The hull hole does not need to be as wide as the prop, because the prop is taken off the motor by removing one nut. The motor can then be placed in the well, tilted forward, and the prop easily reinstalled by leaning over the transom. When the motor is to be removed, the prop is pulled first.

Addressing the cons

I have had one failed outboard-well design that others can learn from. In 2008, we removed the very ill diesel from a friend’s Alberg 35. He did not want the diesel rebuilt or replaced; he wanted it gone forever. Because the Alberg 35 had a long overhanging transom, we felt it would be too difficult to get an outboard motor far enough aft where the shaft could penetrate the transom when tilted up, but still be far enough forward to keep the prop in the water when in the motoring position. Our compromise experiment was to build a fixed open-faced well as far forward as possible with a 20-inch-shaft Mercury 9.9 that could be hoisted out of the well with a tackle and laid on its side in the lazarette for storage. The result was an awkward arrangement, and the shaft proved too short to keep the prop from sucking air in anything but calm water. The lesson there was that a fixed well for anything larger than 6 horsepower is unworkable, and that the 25-inch extra-long shaft is the best choice.

One of the disadvantages of outboard motors is that they are not designed for extreme long-term use, at least compared with the diesel engine. Experts have pointed out that outboard motors wear out sooner and require different, although simple, maintenance. Seawater does splash into the well in rough weather and can cause corrosion if the motor is not rinsed and lubricated occasionally.

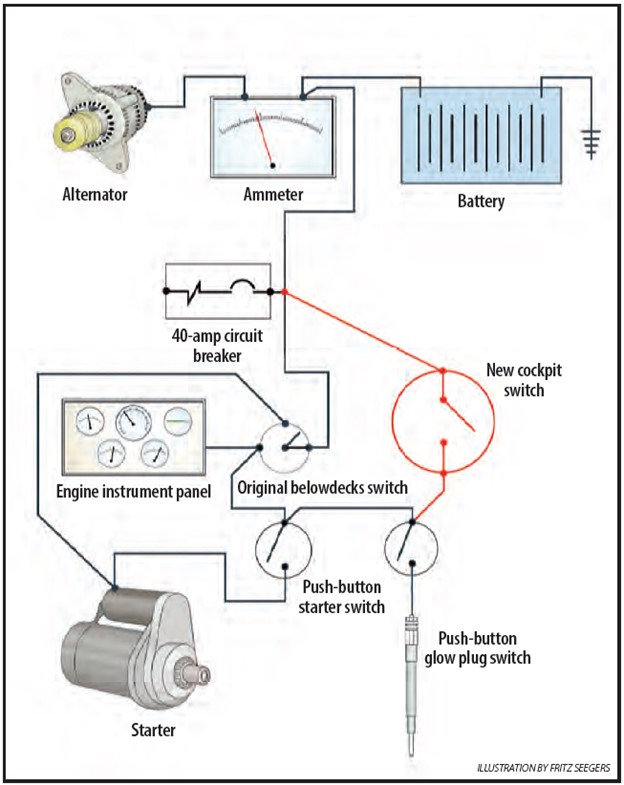

The alternators available on outboard motors have limited output, so you must rely on solar- or wind-charging systems when away from the marina shorepower. I never tried, but you probably do not want to depend on frequently running an outboard motor 24 hours a day. Problems I have had with outboards were typically bad spark plugs or a clogged carburetor, both of which are easy to troubleshoot and fix. I now carry an entire spare carburetor to swap out in minutes. I can then go on my way and thoroughly clean out the clogged carb at my leisure. In the worst case of an irreparable breakdown, you just buy another new or used motor, drop it in, and off you go.

It is true that diesel is less explosive than gas. However, with my outboard-well conversions, two portable gas tanks are stored in the vented lazarette next to the motor and sealed from the rest of the boat. Any extra gas cans carried to extend range are stored in the cockpit side lockers, which are also sealed from the interior and bilge, making fire risk minimal. Typically, you can expect roughly 10 miles per gallon with a 6 to 9.8-horsepower motor in calm conditions at three-quarters throttle. Carrying 15 gallons of gas will get you 150 miles, which is not much of a constraint for most sailors who know how to use winds and currents to their advantage.

In practice, I have had no problem with props coming out of the water in short choppy waves at an ocean inlet with 3-knot current against 15 knots of wind. Rougher conditions may dictate waiting for a change in wind or tide. Most of today’s motors have an over-rev rpm limiter to prevent motor damage from a racing prop. I place the motors as far forward and low as possible and now use only extra-long-shaft models that rarely have the problem of the prop sucking air. Even though they work much better than when placed farther aft on transom bracket, due to the possibility of the prop coming out of the water and the relative low horsepower, we do not attempt to motor in extreme wave conditions. If brute-force motoring in rough seas is your primary concern, then the inboard diesel is the clear winner in terms of power, range, and keeping the prop always in the water.

If retaining the highest resale value for your boat is a primary concern, you should be aware that removing the stock inboard engine will shrink the pool of prospective buyers and probably lower the boat’s resale value. On the other hand, a properly designed and built outboard-well modification, in conjunction with other mods and upgrades, were responsible for one of the Alberg 30s I refitted in 2014 selling for a record price two years later to a sailor who appreciated the conversion.

Benefits of the tilt-up solution

The advantages of a properly designed tilt-up outboard well on a suitable boat include the following:

- Less cost up front and for future maintenance.

- Less weight and wasted space.

- Reduced complexity, which makes motor replacement or repairs easier. You can take the motor to the repair shop instead of bringing a mechanic and all his tools to the boat.

- No need to carry aboard all the specialized tools, maintenance materials, manuals, how-to books, and spare parts necessary for diesel maintenance.

- No fixed prop to snag fish traps and nets under sail.

- If the prop ever gets fouled or damaged, you just tilt up the engine and clear or replace the prop by reaching over the transom.

- Sailing performance is noticeably improved by less drag and turbulence once you remove the inboard’s fixed prop and fill in the prop aperture between keel and rudder.

- You have the ability to swivel the motor for side thrust when maneuvering in marinas.

- An outboard in a well spills no fuel or oil into the bilge.

- The self-contained outboard motor does not need holes in the hull under water for cooling water and for a potentially leaky prop-shaft stuffing box that could fail one day and sink your boat.

- With no need to access a diesel’s exhaust, prop shaft, and other accessories, you can now seal off all the cockpit lockers from the bilge, giving you the added safety of collision bulkheads and less chance of flooding.

- No need for a separate engine starting battery and charging circuit.

- The motor does not radiate unwanted heat into the boat all night when you try to sleep in warm weather after motoring.

- A smaller motor has a smaller environmental impact.

There are also intangible benefits to downsizing to a small self-contained motor located within an outboard well. The more limited range and thrust of a small outboard teaches you to become a better sailor. You will find that, as you hone your sailing skills and gain experience in passage planning, you will notice a corresponding decrease in the horsepower you need. After weighing the relative merits of outboards and diesels, each sailor chooses a system based on his or her own needs.

James Baldwin completed two circumnavigations in Atom and has written three books on his adventures as well as several articles for Good Old Boat. Based in Brunswick, Georgia, James and his wife, Mei, work to assist other cruisers to prepare themselves and their boats for offshore voyages. Find more at atomvoyages.com.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com