Hitting a Tanker in the Dark

Issue 153: Nov/Dec 2023

Sailing through the night is a phenomenal experience. I have had some of my best and worst moments in the inky black of night — ghosting, coasting, flying, and hanging on for dear life through the ocean. The more miles we put under our keel beneath starry skies, the more diligent we are to reevaluate our sail plan and tidy the topsides well before sunset to prepare for the darkest hours of night. Still, as with so many parts of sailing day or night, no amount of preparation or experience can eliminate surprises out on the ocean.

Recently, while sailing south by southwest for multiple days out of the Sea of Cortez and down the main- land coast of Mexico on our Alajuela 48 ketch, Whirlwind, we heard a surprising and new-to-us radio transmission on Channel 16.

The wind was steady, our sails full, and the swell generally behind us with the anchorage we were headed for hours ahead. As we neared the coastline of a locally famous cape, Cabo Corrientes, marine traffic in the area went from complete silence to bustling. There were large commercial vessels, smaller pleasure crafts, and local open-boat fishing vessels (pangas) setting and checking their long lines. All of this traffic, coupled with confused seas stretching from the notorious cape, means this stretch of water requires vigilance day and night.

Before dark we turned our radar on, put a reef in the mainsail, and tidied the decks. I tucked the kids in and my husband, Mike, took the first watch. I had been off watch for a mere half hour when he woke me up to say he needed me. “Maurisa, on deck. Things are happening out here and I need you to get up.”

In the 12 years we have been sailing together, he has never — not once — woken me up for anything. He has tacked, jibed, reefed, raised, and lowered sails without asking for assistance. So why now? What was happening?, I wondered, with a curious knot beginning to twist in my stomach. Waking up, I listened for clues about what was going on. All was quiet but the sweet sound of water rushing by the hull. I scooted out of bed while feeling the motion of our boat; we seemed to be sailing along just fine.

Then the radio crackled a bit and an older male voice came through loud and clear, “I just hit a tanker.”

The voice was calm as can be.

What? Did I hear that right? My thoughts raced and I hastened dressing. I called up toward the open hatch aft of the cockpit, “Mike, did he just say they hit a tanker?”

“That’s what I heard. It is the second time. There is a lot of traffic out here and I need you to monitor the radio, the AIS, and the radar. I will sail the boat and watch for boats.”

I rubbed my eyes, and planted myself into the navigation station. I looked down at the small notepad in which we typically record the date and time, our latitude and longitude, and course and speed during multiday passages. I recorded all the current information just before a new radio transmission came through from the vessel in distress. I flipped the page and quickly recorded their latitude and longitude, with the name Falcon below it. Then I searched and marked this location on Navionics. I saw we were about 12 miles north and heading in their direction.

Looking at our AIS, I also saw the tanker that was heading north. I recorded all the information on the screen. Mike got a visual on the tanker when it appeared on the horizon, and could identify by its running lights that we were on a safe course to pass port to port with a good amount of distance between us. He attempted to make radio contact with the tanker in two different ways: He hailed the vessel on the VHF radio and made a DSC (Digital Selective Call). No answer.

There was another boat communicating with Falcon named Mandolyn, which was also sailing southbound on the coast and moving in Falcon’s direction. I found Mandolyn on our AIS and saw they were closer to shore, a bit farther north, and moving more slowly than we were. I realized we were the vessel closest to Falcon, and the man came on the radio again with an updated location and few details. He was drifting and had his spreader lights on. He stated calmly, and I promptly transcribed, “The bow is smashed and the boat is not taking on any water yet.”

The “yet” was particularly troubling. I hailed him on the radio and made brief contact, letting him know that we were also aware of his location. I relayed ours and told him we were coming toward him. I communicated with Mandolyn as well and confirmed that we were both making our way toward Falcon.

I quickly realized I needed to ask Falcon for some more details, but neither we nor the other vessel, with whom we remained in contact, were able to reach Falcon. At this point, the wind was starting to die, so we pulled down our sails, turned on the motor, and made haste in Falcon’s direction.

For the next two hours, the man on Falcon came on the radio, calmly stating his slightly changing latitude and longitude, but never again responded to direct communication. Mike and I discussed how best to handle this impending encounter. There were so many unknowns. We did not know how many people were on board, if anyone was injured, or if there was anything or anybody in the water nearby. I compiled a short list of questions on our notepad so that if we made contact again, I would try to get more information.

Just after midnight, we caught sight of Falcon’s spreader lights in the distance. I hailed the man again, and when I made contact, I cut to the chase: Number of people aboard? Two, named Dave and Patti. Injuries? None. Lines/ debris in the water? Not sure. Requests? Come across Falcon’s bow and tell him what we see.

In the pitch black of night, I got out our cordless Makita flashlight to help us see the bow. We approached cautiously, running with the 5- to 6-foot swell. It was difficult to make out Falcon’s lights to determine which way they were facing. Its running lights were dim, low, and rhythmically obscured by their dinghy and other items on deck.

We slowly circled the boat three times, rocking broadly from side to side as we turned through every angle with the swell. We were communicating with Falcon on the handheld VHF radio the entire time, letting them know what we saw. Because their bow was smashed, they were staying in the cockpit. We saw that one anchor was dangling off the port bow, along with part of the bow pulpit and rail system. The drum on the roller furler didn’t look right, and the forestay had a deep sag to it. More of their rail system was hanging low off the starboard bow. Although we could not make them out exactly, we could see dark gashes in the fiberglass bow on the port and starboard. “Smooshed” was the word we settled on to describe the nose of their bow.

So what now?

Falcon had been heading to a port about 50 miles to the southeast. Our planned destination was about 30 miles southeast. The other boat trailing behind was new to the area and heading about 40 miles southeast. But the nearest port with a haulout and rigger was about 70 miles north-northwest and into the swell. We strongly discouraged Falcon from pointing their bow into the swell. It seemed a miracle that their boat was dry down below, and we thought moving with the swell would be the best way to possibly keep it dry. We asked if they would like to follow us into the closer harbor we were heading for.

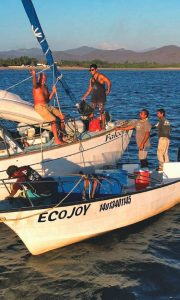

We let Dave know that we had spent a fair amount of time — over a year in total — on this short stretch of coast over the past few years. We knew the bay well, and knew some local pangueros (fiberglass open-boat men) in the small town who would likely be able to assist them with enough of a repair to get Falcon north to a proper haulout facility. We offered to pilot them at whatever speed they were comfortable with.

Together, we decided that we would motor between 4 and 5 knots in the direction of Punta Perula and anchor at the head of Bahia Chamela. Falcon would need to set a stern anchor, and we were confident that the space and protection in the bay would accommodate that. The third boat planned to follow us for a bit and if all appeared well, would continue on to its original destination farther down the coast.

For the next four-plus hours, Falcon stayed quite close to us as we motored. Once we came around Punta Perula, we saw that there were an exceptional number of boats — over 20 — in the anchorage; there are usually far fewer. At 6 a.m., we were inside the protection of the anchorage and able to set our hooks well away from the field of other boats. When the sun rose, it was time to meet the crew of Falcon and reflect on the previous night’s events.

The Takeaway

The couple aboard the Cal 2-46, Falcon, was Dave and Patti — 78 and 84 years old, respectively. Patti was on watch when the collision happened and shared her experience openly and honestly. While she had gotten some instruction on using the AIS, she was still confused and did not really understand how to operate it properly. She thought the tanker’s lights were extremely dim, and in the darkness, she had a difficult time figuring out which way it was moving. Patti said she attempted to change course but was unable to. They had been sailing on a run, by the lee, and she could not adjust the course enough without having to jibe.

Dave and Patti were very fortunate to have made it through the incident with just a damaged boat. The lessons from this unfortunate yet avoidable event are evident. As mariners, we need to know that our navigation lights are operational and placed for prime visibility. When on watch, crewmembers should know how to read navigational lights of other vessels to determine the direction they are moving in and if they are on a collision course.

Along with knowing how to read and interpret navigation lights, all on-watch crew who take the helm should know how to read and use navigation and communications equipment, including AIS, chart-plotter, VHF, and radar. And if you’re ever in doubt while on watch, it is critical — no matter the hour or rank — to bring crew on deck for assistance with maneuvers, sail changes, to help identify nearby vessels, or even to answer questions about a piece of equipment. Ultimately, whether you sail on an inland lake or on the ocean, knowing your boat, your gear, your crew, and your own personal limitations is of utmost importance to staying safe.

Maurisa Descheemaeker lives and sails with her husband and two kids aboard an Alajuela 48 ketch, Whirlwind. Their firstborn was but a peanut when sailing became a family adventure. Boat by boat, they have put many miles under a handful of keels throughout the Salish Sea, down the Pacific Coast, and south to warmer latitudes.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com