A better way to connect snubbers and bridles to chain

Issue 121: July/Aug 2018

Anchoring can be a straightforward procedure, but there are occasions that demand special strategies. And anchoring as a topic will always provoke lively debate at the beach bar or sailing club, especially when the subject turns to rode: rope or chain. I’m thinking of taking all the chain off my current boat, an F-24 trimaran, because of the weight and because we always anchor in shallow water. For years, though, I used all chain and developed techniques for working with it.

All-chain rode has a lot going for it, but requires the use of a snubber or bridle to prevent damage in the event the rode is drawn taut and the shock-absorbing catenary disappears. Use of the higher-grade chains now on the market allows boaters to get the same strength from smaller, lighter chain. This means less weight to sail around with, but also less weight to provide the beneficial catenary, making the positive attachment of a good snubber even more critical. Attaching a snubber or bridle to chain has always been a challenge, inviting many solutions, none of which is quite perfect.

The ideal connector between snubber and chain has the following attributes:

- It is as strong as the chain.

- It cannot come off the chain, even if it lies in the mud.

- It is easy to attach, preferably with one hand.

- It can be recovered over the bow rollers.

- It must cause no chafe, even if it lies on the bottom.

- It allows the connection of multiple snubber lines for major storms.

- It allows the connection of multiple anchors for major storms.

- It works with either a single snubber line or a bridle.

This is asking a lot. And connectors that were adequate for use with common grade 30 chain may fail when used with the stronger grade 43 and grade 70 chain.

plate ensures the chain cannot release from the plate.

Fortunately, an everyday connector does not need all of these traits, and a storm connector doesn’t have to be quite so easy to use. But existing solutions still fall short:

Chain grab hooks -hold tenaciously as long as a lazy loop of chain is pulling downward but quickly wiggle off if they rest on the bottom when the rode goes slack in calm conditions.

Labyrinth hooks (Mantus Chain Hook and Suncor Chain Hook) -promise to stay on more dependably, but they are only half the strength of grade 70 chain; enough with a snubber, but perhaps not storm-worthy.

The Wichard Locking Chain Grab -has only 30 percent of the working load limit (WLL) of grade 30 chain and has a reputation for distorting and jamming.

The Kong Chain Gripper -is very near the strength of grade 43 chain, but securing it requires screwing in a pin.

The Sea Dog Chain Gripper -is the only slotted plate available, but has proven too weak when used with larger chain sizes. Lacking a locking plate and the balance of a chain-grabber hook, it often falls off the chain before tension can be applied.

There are also the knot and sling options for using rope:

Soft shackles -are as strong as grade 43 chain and resist abrasion reasonably well; cruiser experience suggests they are good for at least a year of regular use. Their best feature is ease of recovery over the bow roller, making them a good choice for monohulls. However, they are fiddly if the snubber has to be attached forward of the roller. The shackle should be at least 3 inches long for ease of handling. The open Kohlhoff style is less prone to jamming up with growth and crud.

A Prusik knot -as used by rock climbers, is fast, dependable, and strong. It holds the chain securely but must be connected to the snubber with a carabiner or shackle, creating a potential weak point.

A rolling hitch -on rope slips at about 30 percent of the WLL of the rope, and at as little as 20 percent of the WLL of chain. (I’ve proven this on a test rig with many different ropes and chains.) As this requires serious weather, most sailors will never observe it, which explains why there are so many success stories. However, numerous long-distance cruisers have reported rolling hitches slipping and now use either two rolling hitches or a camel hitch (a rolling hitch with the final turn reversed in the manner of a Prusik knot). Finally, in any rope solution, the rope must be smaller than the chain, guaranteeing it will be too weak for stronger chains.

I’ve tested all of these devices and knots, and I use them in specific situations. I like the soft shackle and Prusik sling when it’s rough and I want to recover the connector over the bow roller. I like the Mantus hook for everyday use; it’s lightning fast to attach and it’s secure. But for high-strength chain and for severe weather, I’ve come up with a better solution, which I call the Bridle Plate.

Multitasking connector

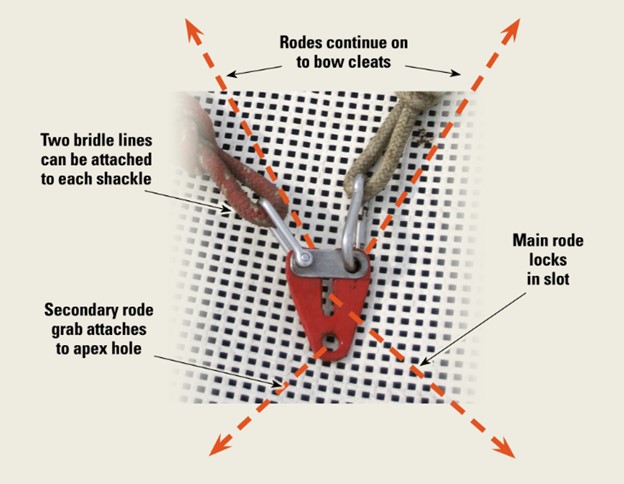

The Bridle Plate is a stronger, more versatile chain grab. Though originally conceived to work with the two separate bridle lines of my 34-foot catamaran, it can be used with a single-line snubber by attaching both connectors to a single eye. I sometimes used it this way to connect a second rode to the main chain.

The chain rode is dropped into the slot, where it’s locked in place by the latch plate when the second bridle line is attached. It’s monstrously strong; even without the latch plate bracing the opening, it’s as strong as grade 43 chain. With the latch plate secured, the Bridle Plate is reinforced against spreading or twisting, forming a closed loop of even greater strength. Locking it on the chain with one hand takes a little practice, but is not difficult to do.

The apex hole allows a secondary rode to be attached, just the thing when two anchors have been deployed for a major storm. Snubbers—two independent sets, if desired—can be attached to large anchor shackles in the corners, keeping the rigging simple and eliminating tangles and chafe. Although there is no redundancy in the plate itself, it is so strong this is not needed. In the unlikely event the Bridle Plate should fail, the rodes remain secured to the bow anyway.

Unfortunately, no manufacturer makes anything quite like the Bridle Plate. It is a DIY item. I have provided design details for making it in a home workshop, but it is also something the local machine shop or even a boatyard could make very easily.

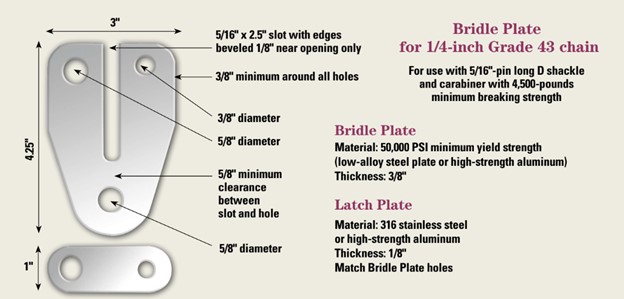

Bridle Plate Specifications

Although I made my early Bridle Plate prototypes from carbon steel and painted or galvanized them, high-strength aluminum alloys are more practical for the DIY fabricator. Stronger than mild steel and 316 stainless steel, these are well-proven in alloy anchors such as the Fortress. Because galvanized chain and aluminum are very close on the galvanic scale, corrosion is minimal. The design of the Bridle Plate is intentionally conservative, and carbon steel examples have been tested to failure with both grade 43 and 1⁄4-inch grade 70 chain.

For grade 43 and grade 70 chain, only medium-strength steel and high-strength aluminum alloys such as 7075 are suitable. Plates made from lower-strength alloys will be too thick to fit between the links, although minor discrepancies can be solved by beveling the slot.

For the grade 30 chain commonly used in anchor rodes, medium-strength steels, 316 or 304 stainless steel, and aluminum alloys can be used by adjusting the thickness of the Bridle Plate in proportion to the yield strength of the chosen metal relative to that of carbon steel.

For example, for use with 1⁄4-inch grade 43 chain, the Bridle Plate should be made of 3⁄8-inch-thick carbon steel. When using 1⁄4-inch grade 30 chain, the Bridle Plate can be made of 6061 aluminum or 316 stainless steel instead of carbon steel plate.

Calculate the plate thickness as follows:

Thickness = 3⁄8-inch × (5,200 ÷ 7,800) × (50,000 ÷ 35,000).

This also gives us 3⁄8 inch for the plate thickness, meaning that a weaker material of the same thickness as the carbon steel is acceptable because grade 30 chain is not as strong as grade 43 chain.

For larger chain sizes, all dimensions should be increased in direct proportion.

The dimensions allow for coatings (galvanized or paint) and normal manufacturing tolerance. There is no harm in being slightly oversize, but minimum clearances between holes and edges must be observed to maintain strength. The fit of the locking plate, shackle, and hole for the long shackle should be easy but not sloppy, to create a smooth swivel.

Chamfer all edges to a 1⁄16-inch radius. Chamfer the entrance of the slot to 1⁄8-inch to allow the chain to enter smoothly. Do not chamfer the bottom of the slot where the chain lies, as this reduces support.

It is helpful, but not vital, if the D shackle is long enough to allow the latch to swing 360 degrees.

The thickness of the Bridle Plate should roughly match the gap between the chain links so that the chain is well supported. Match the slot to the chain. Thicker material better supports the chain. The slot must be slightly wider than the nominal chain size to clear the weld in the chain link.

| Metals | Yield Strength (pounds per square inch) |

| Carbon steel | 50,000 |

| 316 stainless steel | 30,000 |

| 6061 aluminum | 35,000 |

| 7075 aluminum | 61,000 |

| Chain | Minimum Breaking Strengths (MBS) (pounds) |

| Grade 30, 1⁄4-inch | 5,200 |

| Grade 43, 1⁄4-inch | 7,800 |

| Grade 70, 1⁄4-inch | 12,600 |

Resources

Small quantities of the metals specified are often available from local fabricators. One online source is McMaster-Carr: www.mcmaster.com

Drew Frye draws on his training as a chemical engineer and pastimes of climbing and sailing for solving boating problems. He cruises Chesapeake Bay and the mid-Atlantic coast in his Corsair F24 trimaran, using its shoal draft to venture into shallow and less-explored waters.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com