A Cruising Rocket

Issue 130: Jan/Feb 2020

New Zealand designer Ian Farrier, who died in 2017, is legendary in the multihull community for his concept of folding trimarans. His patented Farrier Folding System was a game-changer, making trailerable cruising multihulls a reality for the first time (“Good Old Multihulls,” November 2019).

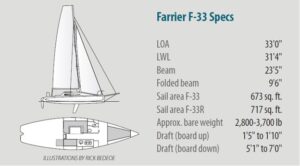

While only nine F-33s were built, all by Keals Marine in Queensland, Australia, this design is representative of other more popular Farrier Marine designs, of which several thousand have been built by amateur and professional builders. Grey Hound, our review boat, is considered a cruising version of the F-33 because it has a shorter mast, smaller sail area, and draws a bit less than the racing version, F-33R.

In a bit of symmetry, Thor Schaette, who, with his wife, Cheryl, owns Grey Hound, conducts an online business selling folding bicycles. They live in Olney, Illinois, and keep Grey Hound in Boulder Marina on Carlyle Lake in south-central Illinois. Thor grew up sailing in Germany, first learning on a 14-foot scow, then later aboard his parents’ 27-footer, which they sailed around Europe. Thirty-five years ago, Thor immigrated to the U.S. but was not much involved in sailing—mostly race cars. Then his parents shipped their Vega 27 to the U.S., and he began sailing again. A J/30 came along, but the need for crew prompted him to move on to a Farrier-designed Corsair F-28R. A divorce occurred about the time the F-33 came into his sailing life, then Cheryl, a seasoned sailor, not long after.

Design and Construction

The inspiration for trimarans comes from Polynesia where dugout canoes (wakas) were—and still are—stabilized for ocean voyages with one or two floats rigged out on long wooden arms or beams. The Polynesians call the floats amas and the beams akas, and these are commonly used terms among multihull aficionados.

Trimarans have long intrigued sailors for their speed and stability. With the amas providing tremendous righting moment, there’s no need for a keel or ballast. If not overloaded, trimarans can remain very light, fast, and, like the F-33, unsinkable. While some feel trimarans are unsafe offshore due to the risk of staying permanently inverted after a capsize (called inverse stability), many home-built cruising trimarans have successfully circumnavigated right-side up, notably Jim Brown’s Searunner series of plywood boats. And, a quick glance at the World Sailing Speed Record Council’s website shows that today, trimarans hold the top 19 speed records over a variety of distances, the most notable being the current Jules Verne Trophy for circumnavigation held by Frenchman Francis Joyon, who in January 2019 set a record for lapping the globe in 40 days, 23 hours, 30 minutes, 30 seconds in his 103-foot trimaran Idec Sport.

While in his 20s, Farrier had an idea for trailerable trimarans that resulted in the patented folding system. He began selling plans for plywood folding trimarans in 1973-74, and always tried to make sailing fast, safe, and affordable.

The F-33 and a similar F-32 incorporated a third version of the Farrier Folding System that allows the amas to fold up against the boat, making it trailerable. These third-generation boats have more clearance over the water and more voluminous amas. Construction is complex; while the main hull is one mold, the entire boat consists of many molded parts (Farrier said there were 57 in the F-27). The amas include a bulkhead that improves load-handling and encapsulates more flotation forward, helping minimize the risk of pitchpoling.

The F-33s are built with premium materials and processes: foam-cored epoxy fiberglass hulls, carbon fiber and fiberglass akas, plus carbon elsewhere as structurally required to handle the massive loads of performance multihulls. Builders limited metal as much as possible; for instance, chainplates are carbon. All parts, including foam core, were vacuum-bagged to consolidate the laminate and remove air voids. Finish is a two-part polyurethane paint.

Deck and Rigging

Stepped on a tabernacle, the fractional rig rotates, either freely or with manual control. Shrouds are Colligo synthetic line with tensioners on the amas and Cheeky Tangs at the top of the mast. Grey Hound, set up as a cruising boat, has a 42-foot aluminum mast, whereas the F-33R racing versions have a 47-foot carbon fiber mast. The genoa has a wire luff, and the working jib is set on a foil; both have continuous-line radial furlers. The wide, swept angle of the shrouds eliminates the need for a backstay. Lazy-jacks help control the full-batten mainsail.

Just forward of the mast, a large, aft-swept carbon fiber daggerboard enables beaching and trailering. Draft with the daggerboard down is 7 feet; draft up is limited by the saildrive to 2 feet 6 inches aft and 2 feet 10 inches at mid-hull. (Sailboatdata.com lists board-down draft as 6 feet 4 inches and board-up draft as 1 foot 5 inches, which may apply to the racing versions.)

Fast multihulls don’t sail dead downwind, so letting the boom out to the shrouds is rare. The Harken Big Boat traveller and 12-to-1 multi-block tackle are close to the helm for dinghy-style sailing. Thor and Cheryl have trouble raising the mainsail due to its weight, so they use a powered winch handle to assist. All lines run through rope clutches to two cabintop winches. Jib and genoa sheets lead to self-tailing winches on the cockpit coamings, with the genoa sheets led via blocks on the akas. The jib is often sheeted very flat to the cabintop block.

Mooring cleats are on the main hull, with none on the amas, necessitating long dock lines. The F-33 has stainless steel bow and stern pulpits. It has a long retractable carbon fiber sprit with a Colligo bobstay.

There is a self-draining anchor locker to store anchors and nets that can be accessed from inside as well. While there’s not much of a foredeck (there’s little need to be up there while sailing), access is easy via the nets and akas. With so many lines there is little room on the cabintop, but again, little need to be there.

Both amas have storage space, typically for fenders and extra sails. The expansive wing nets between the amas and the

hull are taut enough that the footing is steady, yet there is enough give to be luxuriously comfortable for lying down. (The F-33 is off the scale on the high end of my own Penticoff Napability Index of 1-5.)

The long, narrow cockpit feels smallish but is quite comfortable, in part because the boat heels so little (maximum heel for a trimaran is generally around 15 degrees). Grey Hound has two small biminis fore and aft of the mainsheet traveler, which bisects the cockpit and is forward of the short tiller. Grey Hound also has a 150-watt solar panel mounted over the aft bimini to keep two AGM batteries charged.

The transom is open with a long ladder off to one side and ready access to the carbon fiber, daggerboard-style rudder, which will lift clear of the bottom of the hull. Grey Hound’s custom all-carbon cassette allows the board to swing up in a grounding. It replaces the standard kick-up rudder that came with the boat.

Grey Hound’s amas can be folded while in the water with the mast up; a bridle is set up to support the mast while the amas are pulled in. Then, one unfastens the top portion of the nets, loosens the captive aka hold-down bolts, and lifts the akas. Past a certain point they self-fold. The last step is tightening the shrouds to steady the mast. It only takes a few minutes to do all of this.

Accommodations

There is just a single step between the cockpit and cabin sole. Two tinted polycarbonate dropboards close the compan¬ionway. Once below, standing headroom is about 6 feet. Engine access is from the front and a bit difficult. However, the bottom platform step is easily removed, and once you crawl into the engine compartment it’s relatively easy to work on the engine.

To starboard are the electronics and electrics, access to storage under the starboard cockpit seat, and the galley. The galley has a two-burner propane stove, a generous sink with a folding faucet, and 6 feet of smooth countertop with the sink lids down. Forward of the galley is a settee, which can be used as a berth for a shorter person.

To port, opposite the galley, is an overboard-draining ice chest and a U-shaped dinette that converts to a berth.

Three big windows on each side at seated eye level provide excellent light and visibility. Shelves on both sides below the windows, with cubbies behind the seats, provide storage. Saloon ventilation consists of one small opening port in the overhead and pass-through air from the hatch above the V-berth.

The shallow bilge is covered with a simulated teak-and-holly material. There are no handholds and not much need for them, given little heel and a narrow cabin. It’s tight passing between the long starboard settee and the daggerboard trunk, and it’s best to duck your head when going forward through the oval passageway to the fore cabin, where you’ll find a V-berth and storage cubbies. Just aft is the head, with a marine toilet and small sink.

Under Sail

It would not be hyperbole to say that the F-33 is a rocket ship. My test sail took place during a casual race between three Carlyle Lake yacht clubs’ better-performing boats. Soon the knotmeter began its upward climb—9, 12, 13, and then 18 knots as we left J/ Boats far behind on the first leg under main and genoa. The sound and feel of being on plane at that speed is awesome. As water gushed out behind the open transom, we seemed to be jet-propelled. Thor and Cheryl’s personal best speed has been 22 knots, but the F-33 can surpass even this.

At these speeds the F-33 does not feel unstable. Apparent wind moves well forward, and the boat just changes speed with changes in wind velocity. While Grey Hound has slight, reassuring, weather helm, it does not change much with variations in wind pressure.

I could always use the hiking stick or hold the tiller well aft with one hand, even under mainsail alone.

Tacking onto a windward leg, the F-33 stayed flat and easy to trim while furling the genoa and deploying the jib. All maneuvers at any time proved to be quick, light, and easy.

With wind speed at 21 knots apparent and 30 degrees off the starboard bow, I witnessed speeds of 12.5 knots on a dead beat to windward, and at one point I was able to pinch to 25 degrees apparent.

Grey Hound’s PHRF rating with a spinnaker can be –21. On this day, with main and jib, it was rated at a very low +7, although Thor says that Grey Hound’s handicap is often disputed at regattas. We crossed the finish line with the 30-minute lead Grey Hound needed to win on corrected time.

With Thor back on the helm, I walked about the deck, which offers a variety of places to sit or lie down and relax. Cheryl enjoys sitting on the windward ama, one hand lightly on the shroud and legs dangling over the side as the ama flies a foot above the water at dizzying speed. You can stand at the windward shroud and lean out for an even greater “flying” experience. It’s all perfectly steady and stable; even a load on the leeward wing net does not seem to affect handling or speed much. While underway our heel angle never exceeded 5 degrees. Partial cans of soda stayed wher¬ever they were placed. Plates of snacks never budged. Moving about was easy and steady.

Handling under the power of the quiet, 12.5-horsepower Honda saildrive with folding prop was crisp. Under-power cruise speed is 5 to 6 knots. Despite the saildrive, the F-33 is still beachable in the right spot because the drive is well aft. A deep swim ladder and open transom make coming aboard from the water easy. Stepping onto the dock from an ama is equally easy, with no lifelines to contend with. An F-33 docks like a dinghy, but unless the amas are retracted, it uses two slips or a T-head. Tying up was a bit complicated but not unduly so.

The mast can be lowered and the boat loaded onto its trailer for overland travels to new adventures, regattas, races, or storage.

Conclusion

Due to the narrow hull, the accommodations on the F-33 are similar to a 26-foot monohull. Nonetheless, Grey Hound’s previous owners lived aboard for two years. For the cruiser, the trimaran’s small cabin size is often a limitation, but the vast surface area of nets and hard decks makes them spacious and comfortable for living outdoors.

While there have been many Farrier-designed boats that have crossed oceans successfully and won ocean races handily, literature about these feats is always followed with the caveat that these trailerable boats were not designed for ocean use, and you should not expect them to be suitable for ocean-going. Needless to say, they have proven themselves safe and sturdy if sailed prudently.

Ian Farrier, a Multihull Visionary

In 1970, Ian Farrier, then 23 years old, sailed the coast of New Zealand in his home-built 30-foot trimaran during mid-winter storms. Later, after a stormy ocean voyage on a 38-foot monohull, he came away convinced that trimarans were the better way to go.

By 1973, Farrier was living in Australia and building a folding trimaran in his backyard. Fashioning a prototype of the folding mechanism with tin-can metal and nails, he applied for a patent on the Farrier Folding System, which allows the amas to snug up against the hull to narrow the beam to legal road limits. The patent was granted in 1975. In the 1970s he designed several boats in plywood and sold plans and kits beginning with the Trailertri 18 in 1974.

By 1980, the first production fiberglass Farrier design, the 19-foot Tramp, was produced; it evolved into the now-famous and mass-produced F-27.

The Trailertri 720 was introduced in 1984. That same year Farrier set up shop in Chula Vista, California, in what eventually became a 27,000-square-foot building in partnership with Walmart heir John Walton, who had taken a great interest in the Farrier designs. Walton and Farrier established Corsair Marine and employed high-quality building processes, including vacuum-bagging outer hull laminates, the core, and inner laminates simultaneously. With nearly unlimited funding to get past the initial set-up expenses, the production of F-27s ramped up quickly. Although the Farrier-Walton relationship initially worked well, with Walton doing hands-on dirty work in the shop, it eventually soured as Walton desired more design influence.

The relationship broke in 1991, and Farrier returned to Australia with his latest designs to start a new company, Farrier Marine. Still, Corsair worked out a deal to build the new F-24 design under license. By September of that year, Australian builder Ostac built the first production F-31. In 1992, Corsair Marine began selling imported F-31s and building them as well, though it lost the license for not conforming to Farrier’s design specifications.

When Walton founder Sam Walton passed away, John returned to the family business and sold Corsair Marine to Ostac owner Paul Koch for $1. Farrier supported Koch-owned Corsair Marine as long as his design specifications were followed. It didn’t last, and Farrier pulled out once again in December 2000. In 2010, Corsair was acquired by Australian multihull builder Seawind, which continues to build folding trimarans under the Corsair name at its facility in Vietnam.

There are approximately 28 Farrier designs and iterations. The most current boat, the F-22, came off the drawing board in 2006. While an F-39 was built and launched in 2007, right on the heels of the F-32s and F-33s, Farrier was most passionate about the F-22. He viewed it as going back to his visionary roots: faster, safer, simpler, and affordable.

Shortly before Ian Farrier’s death on December 8, 2017, at age 70, a 2016 commentary in Sailing magazine by yacht designer Robert Perry acclaimed the F-27 as one of the four most influential sailboats of all time. This followed the induction in January 2004 of the F-27 into the Sailboat Hall of Fame, the second multihull so honored, following the Hobie 16.

Allen Penticoff, a Good Old Boat contributing editor, is a freelance writer, sailor, and longtime aviator. He has trailer-sailed on every Great Lake and on many inland waters and has had keelboat adventures on fresh and salt water. He owns an American 14.5, a MacGregor 26D, and a 1955 Beister 42-foot steel cutter that he stores as a “someday project.”

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com