…and Two More Lift-Keel Performers

Issue 135: Nov/Dec 2020

Everyone knows that deep draft improves sailing performance but restricts cruising options. The ability to reduce draft would certainly eliminate that conflict, not to mention allow a boat to become trailerable and capable of being launched and retrieved at a ramp.

There are basically two ways to reduce draft. The common and simplest solution is to use either a centerboard or daggerboard in conjunction with fixed shoal-draft ballast in the form of lead, iron, or water. A lift or raised keel, on the other hand, involves lifting the entire primary ballast. From a performance point of view, it’s the better solution since it substantially lowers the ballast center of gravity when sailing. But it requires careful engineering to execute properly.

So, let’s look at two other lift-keel boats to compare to the Seaward 26RK.

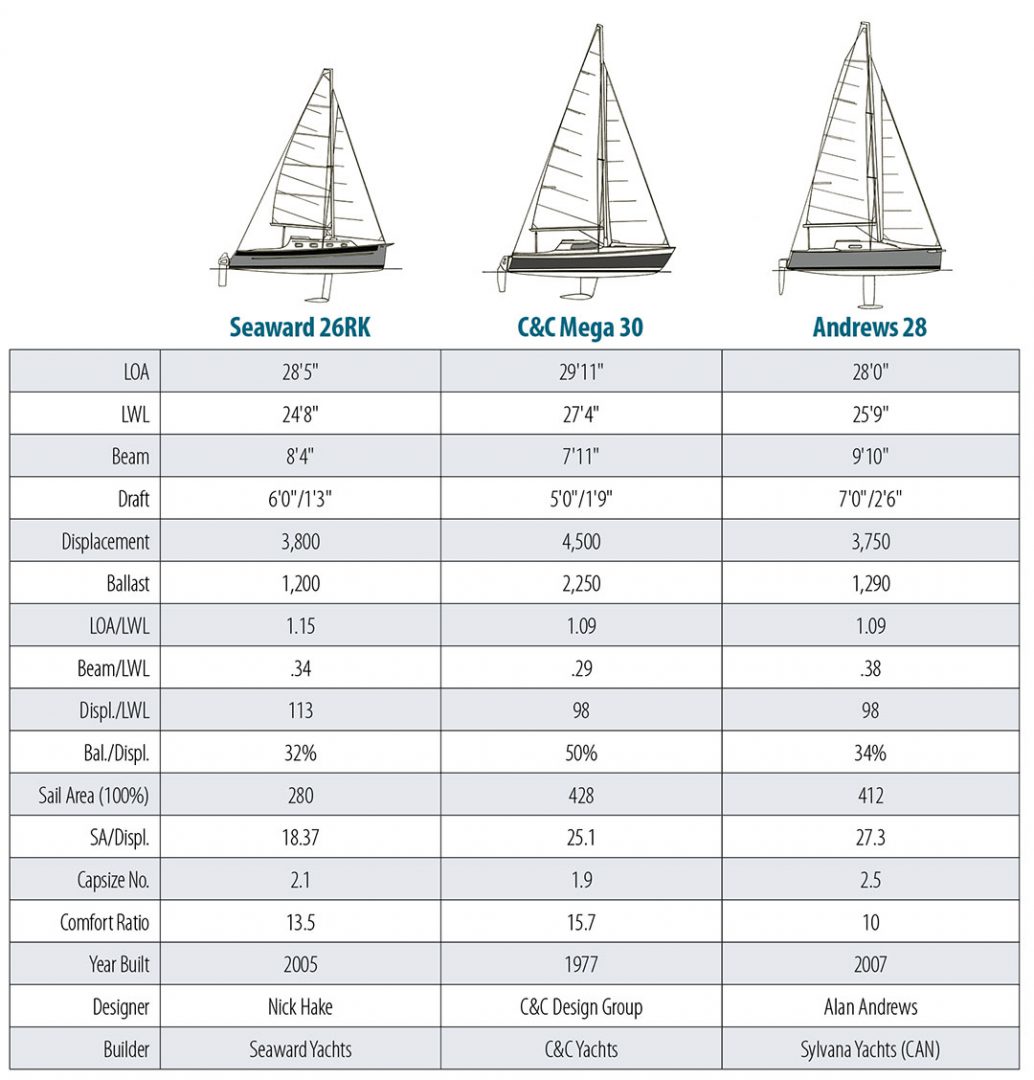

You cannot discuss lift-keel boats without including the Mega 30 (full disclosure, while I was with C&C Design I was project manager for the Mega). The other boat we have chosen is the Andrews 28. The Andrews was awarded “Best Club Racer” in the 2009 Sailing World Boat of the Year contest.

Note that the Mega dates from 1977, while the Seaward and Andrews date from 2005 and 2007, respectively. George Cuthbertson once declared that the Mega suffered from being ahead of her time. Does the fact that the Seaward and the Andrews emerged some 30 years after the Mega prove him right?

Raising the 2,250-pound keel on the Mega was achieved with a screw jack that could be operated manually with a winch handle or an optional electric motor. The Seaward uses an electric winch to hoist a cable attached to the keel, while the Andrews uses a cable winch that can be hand cranked or operated by a battery-powered drill. Neither the Mega nor the Andrews actually encourage operating the boat with the keel raised, whereas the Seaward does promote this for shoal-water sailing.

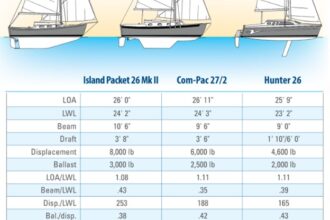

At just under 30 feet, the Mega is the largest of the three, but that does not include the transom-hung rudder. I strongly suspect that the Seaward’s length overall listed at 28 feet 5 inches does include the rudder, and even possibly the bowsprit. So, in evaluating the true lengths of these boats it would be better, as always, to look at waterline length. In that regard the Mega is still the largest, being almost 3 feet longer than the Seaward and a foot and a half longer than the Andrews.

Now let’s look at beam. This is a critical dimension for trailerable boats, since almost all state and provincial jurisdictions allow 8-foot beam, and a good many allow 8 feet 6 inches; anything over that usually requires special permits or even escort vehicles. The Mega, while considerably longer than the other two boats, is by far the narrowest at just under that all-important 8-foot measurement. The Seaward at 8 feet 4 inches slides under that 8 feet 6 inches, while the Andrews is a remarkable 9 feet 10 inches, requiring careful planning to make long highway journeys.

The Seaward and the Andrews have nearly the same displacement at about 3,800 pounds, while the Mega tips the scales at 4,500 pounds. However, because of her longer waterline, the Mega has the same exceptionally low displacement/length waterline ratio of 98 as the Andrews, while the Seaward is still no slouch at 113. The Mega’s heavier displacement is almost all in her 1,000-pound ballast, giving her a ballast/displacement ratio of a remarkable 50 percent compared to 32 and 34 percent for the other two boats. This heavier ballast was an attempt to compensate for her narrow beam. The Seaward and the Andrews have 1 and 2 feet more draft than the Mega, which would certainly help to achieve a lower center of gravity, especially with their generous bulbs.

Also note the similarity in the rigs of these three boats that span 30 years of sailing development. All three incorporate large mains with small, easily tacked jibs, swept-back spreaders and shrouds, and deck-stepped masts. The Seaward has the smallest sail area at 280 square feet, with the Mega having the largest at 428 square feet, and the Andrews at 412. The latter two lead to very impressive sail area/displacement ratios of 25 and 27 respectively, compared to the Seaward’s more conservative 18.

All have the ability to lift their transom-hung rudders as well as their keels, with the Seaward and Andrews using rudder cages to raise and lower the foil vertically, while the Mega pivots the rudder blade in the welded aluminum rudder head.

The challenge in any lightweight, shallow-bilged, trailerable boat is to achieve standing headroom. This inevitably results in increased freeboard and high topsides. The Mega and the Seaward employed some visual trickery in the form of shear bands and graphics to try to reduce the visual impression of height, but the Andrews does not, and perhaps suffers a little aesthetically because of it.

Did these boats achieve their goals? I know from personal experience sailing the Mega upwind that even that extra 1,000 pounds of ballast did not provide enough increase in stability to overcome the large sail plan on that extremely narrow beam. I suspect the Seaward with her smaller sail plan, slightly wider beam, and deeper draft would fare better, but that almost 10 feet of beam on the Andrews, combined with a 7-foot draft, would certainly let her stand on her feet upwind in a breeze.

Good Old Boat Technical Editor Rob Mazza set out on his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, when he began working for Cuthbertson & Cassian. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com