. . . and Two More Family Cruisers

Issue 136: Jan/Feb 2021

John Clarke refers to the Beneteau Oceanis 351 as a family cruiser. So, let’s start by describing the evolution of this concept.

In the days of the dual-purpose cruiser/racer back in the 1960s and ’70s, designers afforded equal consideration to the conflicting demands of racing and cruising, with the inevitable compromises that this entailed. To eliminate these compromises, the market started to fragment between true racers and true cruisers. But by the 1990s, the majority of racing was either in one-designs (even offshore one-designs), or in the Performance Handicap Racing Fleet (PHRF).

The majority of boats competing under PHRF were those older, dual-purpose designs. If production builders wanted to stay in business, they had to offer something different than what was available on the used boat market, and since the popularity of racing generally was declining, builders shifted to create more comfortable family cruisers. These were easier to sail and incorporated large cockpits for lounging and entertaining, combined with generous interior amenities. To achieve these goals, beams and freeboards increased, with boats getting notably wider aft.

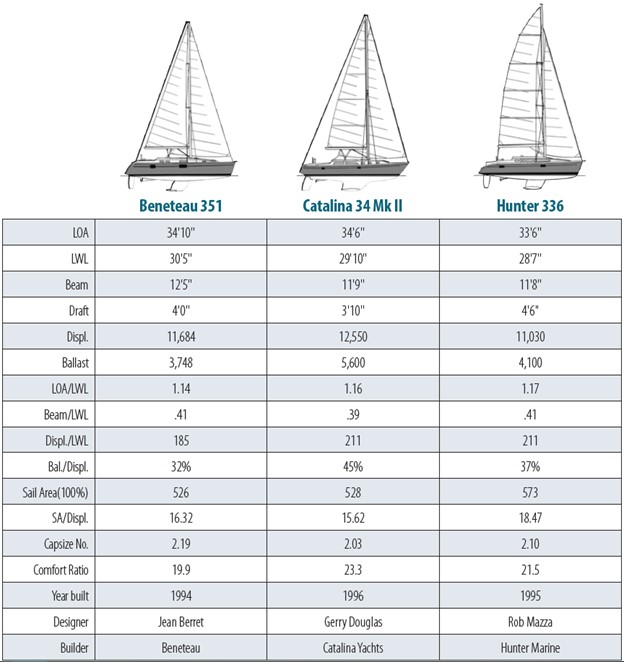

By the 1990s, there were really only three large production sailboat builders in North America— Catalina, Hunter, and Beneteau. So it makes sense to draw our comparison boats from those other two builders, looking specifically at the Catalina 34 Mk II (wing keel) and the Hunter 336. I’m personally familiar with both boats, having spent many a pleasant hour in the cockpit of a friend’s Catalina 34 Mk II, and having designed the 336 while I was with Hunter.

Before we get to the numbers, let’s look at rigs. Note that I have shown the Beneteau with a furling main, since this is the configuration in the company’s promotional material and is incorporated on our review boat. While the Beneteau employs moderately swept-back spreaders to contribute to fore-and-aft mast support, the Hunter takes this to the extreme with a B&R rig on which the shrouds take the entire fore-and-aft loading, eliminating the need for a fixed backstay. This allows a much larger roach on the fully battened mainsail, which makes up for the lack of overlap in the jib. Note also that the Beneteau and the Catalina are traditional CCA/IOR masthead rigs, while the Hunter incorporates a fractional rig with a small headsail. This is not only easier to handle, but the small jib sheets inside the shrouds, which are taken out to maximum beam at the shear.

Now let’s look at the numbers. If you compare waterline lengths, you would conclude that the Beneteau is the largest at 30 feet 5 inches, while the Hunter is the smallest at 28 feet 7 inches, and the Catalina somewhat in the middle at 29 feet 10 inches. But is length the best way to measure size? Based on displacement, the Catalina is the largest at 12,550 pounds, the Beneteau next at 11,684 pounds, and the Hunter still the smallest at 11,030 pounds. However, with displacements within 1,500 pounds of each other, the Beneteau’s longer waterline length results in the lowest displacement/waterline length ratio of a sprightly 185, while the Catalina and Hunter are equal at a still quite light 211.

In light of the desire for increased interior volume, notice the generous beams at 12 feet 5 inches, 11 feet 9 inches, and 11 feet 8 inches, respectively. This results in beam/ waterline length ratios of .41, .39, and .41. That is, the beams of these boats average about 40 percent of their lengths! The Catalina 34 Mk II, which is a reworked version of the older 1985 Catalina 34, has the lowest beam/waterline length ratio.

Next, notice the draft comparison. Granted, I have used the wing keel version of the Catalina 34 to better equate with the other boats, but with drafts between 3 feet 10 inches and 4 feet 6 inches, these boats are not designed for performance sailing upwind, despite the incorporation of bulbs and wings. Family cruising necessitates reduced draft but still enough to achieve acceptable upwind performance. In that respect, the 336 should have the edge, especially in light air.

The wider beam of the Beneteau could explain her lower ballast weight of 3,748 pounds and lower ballast/ displacement ratio of 32 percent compared to the Hunter at 37 percent with 4,100 pounds of ballast, and the comparatively narrower and heavier Catalina at 45 percent with a substantially heavier 5,600 pounds of lead.

The Hunter has the largest measured sail area at 573 square feet, compared to the Beneteau and Catalina at about 527 square feet. Thus, because the Hunter is also the lightest of the three, she has a substantially higher sail area/displacement ratio of 18.5 compared to 15.62 for the older and heavier Catalina and 16.32 for the Beneteau.

The wide beams and lighter displacements of these boats are detrimental to achieving a capsize number under the desired threshold of 2. This again illustrates the decision to maximize interior volume at the expense of offshore considerations. The light displacements and wider beams result in lower comfort ratios, with the lightest and widest Beneteau coming in at 19.9, the heavier and relatively narrower Catalina faring the best at 23.3, and the Hunter in the middle at 21.5.

All three of these boats fulfill the 1990s design philosophy of the family cruiser, but I have to admit that my eye is drawn to the more traditional shear of the Catalina and the Hunter.

Rob Mazza is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. He set out on his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, when he began working for Cuthbertson & Cassian. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com