…and Two More CCA-Onspired Classics

Issue 137: March/April 2021

Carl Alberg developed a design aesthetic based on the Cruising Club of America (CCA) yachts of the 1950s and ’60s, and he never really diverted from that style. And why would he? Starting with the Pearson Triton in 1958 and following in 1962 with the similar and equally successful Alberg 30 for Kurt Hansen at Whitby Boat Works, his designs were well received for family cruising.

In 1967, the Alberg 37 followed in that same family tradition. So, it is fitting that we find two other boats from that period that share that CCA aesthetic, each designed by an equally well-known designer; the 1965 Olin Stephens-designed Grampian Classic 37 (also built on Lake Ontario), and the slightly smaller 1966 Bill Luders-designed Luders 36 built by Cheoy Lee in Hong Kong.

All three boats feature the same CCA characteristics of long overhangs, counter sterns, full keel, and low-aspect-ratio, masthead sloop rigs. Keep in mind, however, that each is contemporary with the introduction of the fin keel and spade rudder on Bill Lapworth’s Cal 40 in 1963, Dick Carter’s Rabbit in 1965, and George Cuthbertson’s Red Jacket in 1966, and thus each represents the culmination of the traditional CCA era.

The Alberg 37 and the Grampian 37 are pretty well identical in overall length and only 3 inches different in waterline length, with each having 16,800 pounds of displacement. This makes one wonder if Hansen may not have been influenced in his commission of the Alberg 37 by the competing 37-footer being built further up the lake.

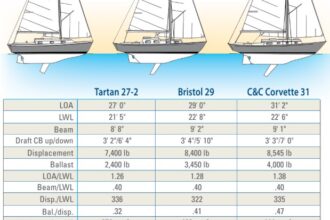

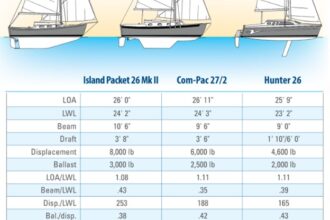

The Luders design, on the other hand, is about a foot-and-a-half shorter and 1,800 pounds lighter. For all three boats, this results in very conservative displacement/waterline length ratios of 403, 415, and 429, respectively. With numbers this high, these really are cruising-oriented designs. Remember, though, that the CCA rule was essentially a waterline-length rule, so boats tended to have shorter waterlines for their displacements. This is, of course, another reason for the long overhangs, with length overall/waterline length ratios all around 1.4.

Beams are almost identical, with the shorter Luders having the 1-inch wider beam of 10 feet 3 inches, resulting in narrowish beam/waterline length ratios of .38 and .39 for the Alberg and Grampian, and .41 for the Luders. This narrowish beam combined with the heavy displacement produces very safe capsize numbers of 1.59. 1.60, and 1.67, all well below the threshold value of 2, and all indicative of good, safe sea boats. The heavy displacement, long overhangs, and relatively narrow beams also produce consistently high comfort ratios in the high 30s.

Sail areas are also very consistent, with each boat having sail area/displacement ratios in the mid 15s, indicating conservative, but good, performance. As is typical of most CCA designs of this period, ballast/displacement ratios are between 35 and 40 percent, which, when combined with the narrower beams, indicates a lower stability. However, that would be countered by the lower heeling moment generated by the squatter CCA rigs with their shorter masts and longer booms. Also, the CCA rule tried to measure stability by incorporating the ballast/displacement ratio in the rule. This resulted in designers working to keep ballast weights low and achieving increased stability by incorporating cast bronze mast steps and centerboard boxes, as well as locating large numbers of heavy batteries below the cabin sole.

These boats won’t offer stellar performance compared to the lighter, beamer, fin-keeled sisters emerging during this transitional period in yacht design, but they do guarantee comfortable cruising potential. Equally important, to my eye at least, is that each is a strikingly good-looking boat, with perhaps the Luders having the slight edge in this regard.

In looking at these three boats, I’m again reminded of Gerry Douglas’ theory that one’s tastes in yacht design were established by the boats to which one was exposed at 14 years old. This view of classic yacht design beauty was recently echoed by Bob Perry in Fiona McGlynn’s profile (“The Maestro” November/December 2020). Bob is quoted as being greatly inspired as a teenager by his first sight of a Phil Rhodes-designed Chesapeake 32, then saying: “It’s interesting, now that I’m 73, I look at the modern boats and I think, ‘If I was 15 today, looking at those boats, would I want to be a yacht designer?’ Probably not.”

I too was in my teens when these boats were launched, which is undoubtedly influencing my opinion. However, if we stick with the theory that one’s tastes are locked in at 14, then younger people than Bob and myself may find boats of the mid-’80s more appealing, and I can’t really fault that. Having said that, I expect every sailor would look upon these boats as classics, well worth restoring and updating. That’s what I’m doing with my own 1965-designed C&C Corvette 31. Long may they all continue!

Good Old Boat Technical Editor Rob Mazza set out on his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, when he began working for Cuthbertson & Cassian. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com