Issue 132: May/June 2020

I’ve heard the refrain, over and over: “I would never leave the dock without paper charts aboard!” It rubs me the wrong way.

I’ve heard the refrain, over and over: “I would never leave the dock without paper charts aboard!” It rubs me the wrong way.

I think it’s often used as a declaration of one’s superior saltiness and seamanship. It’s a judgment that the world is now filled with gadget buyers who are too reliant on their devices and who are disconnected from the basics, the fundamental navigation arts. “These poor saps are going to be in a sorry state when the Iranians hack our GPS constellation and they’re lost somewhere under sail, no idea what to do next. While these technophiles sail in hopeless circles, not a self-sufficient bone in their bodies—reaching for their EPIRBs—I’ll sail past on my rhumb line, plotting points on my paper chart…”

That’s what I hear when the paper-chart declarations are made, and I don’t buy it. I asked the question of readers in February’s The Dogwatch. The overwhelming majority of responders echoed the feeling that paper charts are necessary, that sailing without them is foolish. I may be in the minority.

Respectfully, let’s look at the oft-cited risks, starting with lightning. Consider the odds. First, the odds are low that your boat will be struck by lightning. If it does happen, for paper charts to be the lifesaver some claim, all of the following must happen as well: The lightning kills all your electrics, you’re underway and cannot reach port without your electronic navigation systems, and the lightning doesn’t cause other damage that is so significant that navigation becomes irrelevant. This is not a realistic concern.

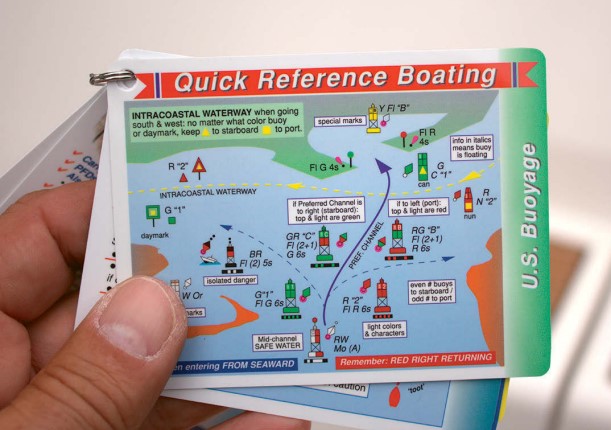

Next, consider the oft-cited threat that hackers take down the GPS constellation. I’m betting this isn’t likely either, but I’m not qualified to say, so let’s go with it and assume the risk is real. So what? It’s not a threat. GPS has largely given way to a global navigation satellite system (GNSS). In other words, most equipment aboard boats today use signals from American GPS satellites and Russian GLONASS satellites.

I talked to Benjamin, a technician at Garmin, about this. I sought confirmation that should the GPS system go down, Garmin’s units would continue to work without interruption, pulling signals from the GLONASS system. He said they’ve never been able to test whether their devices would work if the GPS system was down and the GLONASS system was up, but that their hardware will deliver a position fix so long as any three satellites are received.

Consider too that several more systems are recently online, and that device manufacturers will likely begin to use these signals as well. These are Galileo (the European Union system), BeiDou (the Chinese system), and Quasi-Zenith (the Japanese system of four satellites that augments GPS in the Asia-Oceania region).

And what about solar flares or ground-based jamming of GNSS signals? Both do happen—the latter happens consistently in some parts of the world. Benjamin at Garmin said that in both cases, the signals from all types of GNSS systems are likely to be affected equally. In the case of solar flares, the satellites are not affected, only the ability of the signal to travel, thus making the position inaccurate (in terms of meters) or impossible to determine. Regardless, solar flares do not occur often, and they are temporary (typically lasting minutes to hours) and mostly affect only the higher latitudes (in terms of GPS reception). Ground-based jamming happens but is localized and in known areas, like piracy.

Which brings us to the primary fallibilities of electronic navigation tools: loss of power, damage, and failure because, well, complex electrical things break—especially aboard boats. I have a one-word answer to them all: redundancy. Vulnerable stuff aboard a boat isn’t limited to electronics. Lines break, steering systems fail, and winch pawls and springs are susceptible. We anticipate these failures and we carry tools and parts to effect repairs. We carry spares or back-up systems to get us home. It’s no different with our navigation tools, no matter what they’re made of.

For some, redundancy means carrying paper charts in addition to electronic navigation devices. For me, redundancy means carrying several independent electronic means of navigation and having access to separate power supplies. To each his own, but there should be no shame in going paperless. I celebrate the self-sufficient ethos of sailing, and I wouldn’t hesitate to leave the dock without paper charts aboard.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com