A variety of factors contributed to the end of yacht design’s golden age.

Issue 133: July/Aug 2020

I recently finished reading Dick Carter’s autobiography, Dick Carter: Yacht Designer in the Golden Age of Offshore Racing. Beyond the story of Carter’s remarkable career, the book is a reminder that modern yacht designers are no longer familiar names.

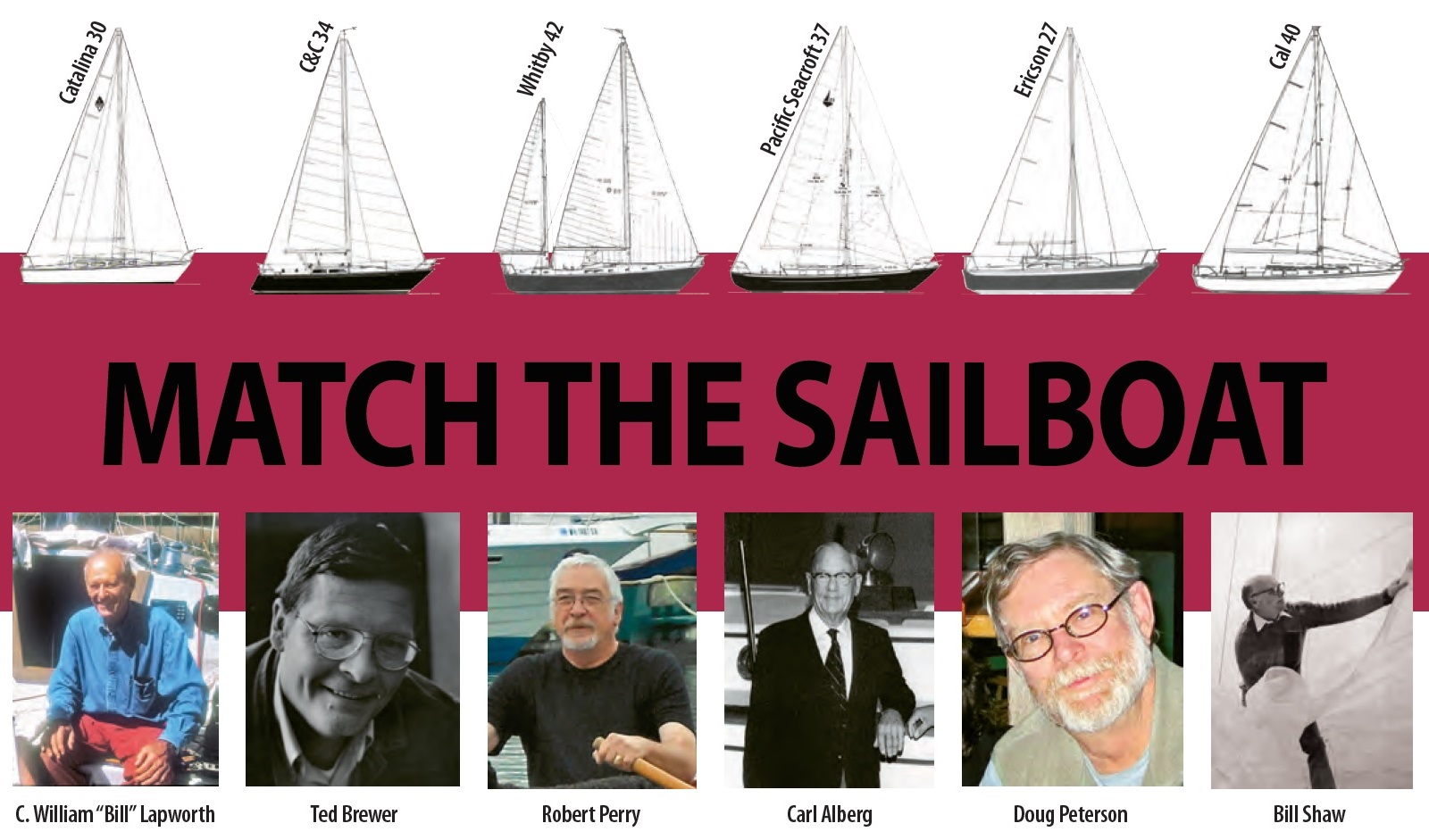

The designer names we know are familiar not only because their boats won races or crossed oceans, but because each brought their own personality and design aesthetic to their projects, so that a sailor could identify, even at a distance, a Phil Rhodes or a Carl Alberg design, as well as boats from the boards of Bill Tripp Jr. or Gary Mull. You could easily distinguish a C&C from a Pearson or a Sabre. Boats from specific designers featured recognizable shear lines, overhangs, and house details; an Aage Nielsen design, for instance, would never be confused with one of Britten Chance’s.

I can’t tell you who drew any of the newer production sailboats in my marina, but I can spot a Pacific Seacraft 37 from a mile away and tell you it’s from Bill Crealock’s drawing board. Some might say I’m a sailor lost in the past who has failed to keep up, but even if there were any truth to the comment, it misses the point. Many things have changed in the boat design world, things will never return to what they once were, and there are fundamental reasons why I can make both of these statements without hesitation (though admittedly perhaps with some nostalgia).

The golden age of yacht design I’m praising didn’t rise until the 1960s, and by the 1990s it was pretty well over. Of course, this period coincides with a post-war economic renewal in North American and European economies, a period when people unleashed their pent-up desire for leisure activities such as sailing. The market for sailboats exploded, and the advent of fiberglass meant that builders had the means to produce them quickly and affordably. Lots of sailboats selling and sailboat racing meant lots of work for lots of sailboat designers.

It was an extraordinary period that benefitted established designers and design houses, such as Sparkman & Stephens, Bill Tripp Jr., Phil Rhodes, Carl Alberg, George Cuthbertson, Bill Lapworth, and Ted Brewer, while at the same time giving rise to new talents such as Dick Carter, Bob Perry, Chuck Paine, Gary Mull, Rob Johnson, Rod Johnstone, Britten Chance, Bruce Kirby, German Frers, Mark Ellis, Ron Holland, Bruce Farr, and Bruce King. The great in-house designers like Bill Shaw, Rob Ball, Gerry Douglas, Frank Butler, Tim Jackett, and many others were equally busy. But this unprecedented heyday doesn’t begin to explain why things are so different today.

Computers and Modeling

The Texas Instruments calculator didn’t appear until 1973, so designers determined the calculations for many early boats with only a slide rule, if that. And some of them drew a few early career-launching boats in bedrooms or kitchens, pencil on paper, with only a copy of Skene’s Elements of Yacht Design as a reference. It’s not surprising that many of the designers of this era continued to work by hand even after the development of design software, often turning their hand drawings over to others to digitize.

The introduction of computers in yacht design did more than just ease the workload and add convenience. Computerized line-drawing programs, solid modeling, and velocity prediction and flow visualization programs disrupted yacht design protocol. In the past, owners and designers had to actually build and competitively sail a new design to evaluate its performance, assuming optimum sails and crew. It would take at least a season to assess a new design while the boat was racing in fleets that included new boats from other designers. In that environment, boats that won races either on actual or corrected time garnered name recognition (and more work) for the respective designers.

Today, through advanced and accurate software, the performance and success of a sailboat design can be determined in a matter of minutes without even building the boat.

Materials

Many of the well-known yacht designers of yesteryear established their careers with their first designs, such as Carter with Rabbit, Doug Peterson with Gambare, Bob Perry with the Valiant 40, and Bruce Kirby (he of later Laser fame) with his iterations of the International 14 dinghies. In fact, Carter, Kirby, and Peterson designed their first boats for their own use. This was possible because in the 1960s and ’70s it wasn’t terribly expensive to build a boat in wood or steel, even as a one-off, costing little more than a production boat built of the same material. Ironically, since then contemporary materials and techniques have widened the price differential between custom and production boats. Composite construction (fiberglass laminates and multiuse molds), with the evolution of lighter-weight, high-stiffness, and high-strength fibers, resins, cores, and more sophisticated and stringent lamination methods, reduced the cost of production boat building while increasing the cost of custom, one-off builds. Today, unless they had significant means, a young new designer looking to make a name for themselves would not be able to design and build a competitive one-off to do so.

Playing by the Rules

As design software became more common and builders adopted new construction materials, another, perhaps more significant, change took place. Earlier designers benefited from stable handicap and design rules that created opportunities for clever designers to “optimize” or exploit loopholes. The more a designer could identify areas in which to capitalize, the more it enhanced his reputation. In fact, it wasn’t the designer’s job to draw the fastest boat possible, but to design the fastest boat within the parameters of a rule—that is, to produce a boat that, according to the rules, should be slow but was indeed relatively fast.

Thus, the goal was a boat with the greatest difference between its rating and its speed, a boat that started the race with a rating edge that allowed it to win on corrected time, not actual time. This era of racing design rules (RORC, CCA, and ultimately IOR), coupled with a sailing population willing to race dual-purpose boats offshore and to buy a new boat every few years, allowed the yacht design profession to flourish in what Carter calls the “Golden Age of Offshore Racing.”

What happened? I would argue, and Carter agrees, that the designers, in league with the owners, sailmakers, and builders, are responsible for ending their Golden Age. To beat the IOR rule, they designed stripped-out, distorted, wide-beam, deep-draft, lightweight boats. None of these design trends were healthy for the sport, as the boats increasingly had limited or no cruising capabilities. Thus, a very narrow used boat market for these boats existed. And when the IOR rating rule was abandoned, the IOR-competitive boats became quickly obsolete, as had the CCA-conforming boats before them.

But this time, rather than a new design rule replacing IOR, racing bodies abandoned design rules altogether and replaced them with the true handicap rules we use today, rules derived from velocity prediction software. This meant there was no longer a rule for a clever designer to manipulate or beat, no longer a name for oneself to make.

One Design

As a result of all of the above, or simply in addition to everything else, one-design racing became increasingly popular. Today, a fleet of 30 or so one-design boats on a course does not represent the efforts of a dozen or so designers, but only one. No longer are there “design duels” in racing, contests between different boats that are actually proxy contests between their designers. In fact, the majority of yacht racing today happens without regard to any competitive designer influence.

While there are still great designers from this past era practicing today—among them Bob Perry, Jim Taylor, Dave Pedrick, and Bruce Farr—where is the up-and-coming crop of designers? The “young turks” ready to challenge the establishment and fill the shoes of their elders? I can’t name any. The vast majority of sailboats on display at boat shows are increasingly hard to differentiate from one another. Almost all have plum stems, fat back ends, twin wheels (an innovation that Dick Carter takes credit for, by the way), and walk-through transoms. How many of us can put a designer’s name to any of these boats?

Yet, while it’s easy to dismiss these boats’ lack of individuality, it’s also easy to admire the benefits of modern designs, such as the greater amount of space below, on deck, and in the cockpit, the increases in speed, the ease of sail handling, the lack of deck clutter, and the contemporary amenities. Who hasn’t chartered one of these boats—monohull or catamaran—for a tropical adventure and returned home quite happy without giving a second thought to the name of the person who designed the boat?

So, while we might mourn the lack of young new designers and debate the reasons for their absence, more importantly we should celebrate and honor the designers who have made our good old boats so distinctive and unique. The boats from this golden age of yacht design continue to offer affordable pathways to a life afloat for thousands of people who can choose from the work of a multitude of talented and well-known designers to perfectly match their own requirements. In that regard we are all exceptionally fortunate. Let’s lift a glass in tribute to all the designers of our good old boats. We may never see their like again.

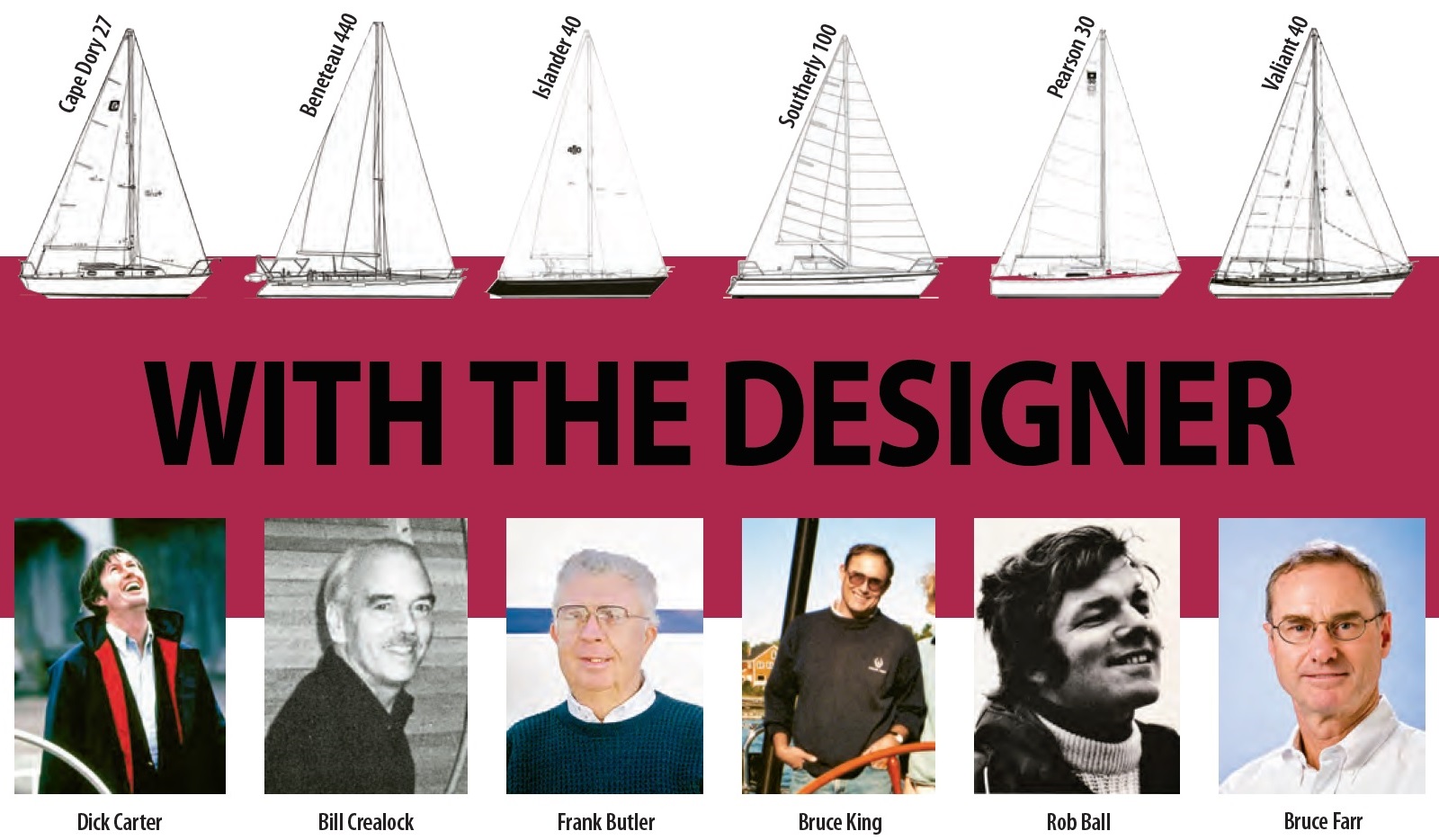

Match the Sailboat to the Designer Key

Shaw: Pearson 30, Peterson: Islander 40, Farr: Beneteau 440, Ball: C&C 34, Crealock: Pacific Seacraft 37, Alberg: Cape Dory 27, Butler: Catalina 30, Lapworth: Cal 40, Brewer: Whitby 42, Perry: Valiant 40, Carter: Southerly 100, King: Ericson 27

Rob Mazza is a Good Old Boat contributing editor. He set out on his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, when he began working for Cuthbertson & Cas¬sian. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com