… and Two More Transitional Centerboard Racer/Cruisers

Issue 143: March/April 2022

You may remember that in Good Old Boat’s November/December 2021 issue, we reviewed three centerboarders from the late 1970s and early ’80s in relation to the Sabre 38. However, while two of the boats—the Sabre and the C&C 40—offered the centerboard as an option, only the innovative Pearson 40 made it the standard configuration. For this review comparing the Pearson 39, C&C 40 Crusader, and Tartan 37, all three boats from the late ’60s and early ’70s came standard with a centerboard.

You may remember that in Good Old Boat’s November/December 2021 issue, we reviewed three centerboarders from the late 1970s and early ’80s in relation to the Sabre 38. However, while two of the boats—the Sabre and the C&C 40—offered the centerboard as an option, only the innovative Pearson 40 made it the standard configuration. For this review comparing the Pearson 39, C&C 40 Crusader, and Tartan 37, all three boats from the late ’60s and early ’70s came standard with a centerboard.

One can’t help but notice this interesting transition from centerboards as the standard configuration in the 1960s, shifting to an option in the 1970s and ’80s, and today being virtually nonexistent in new, larger production fiberglass cruising sailboats. One reason for this transition is that the late ’60s and early ’70s were the last years of the CCA rule, under which centerboarders such as the S&S-designed Finisterre, the Rhodes-designed Carina, and the Cuthbertson-designed Inishfree dominated offshore racing, prompting the centerboard to become a common feature in racer/cruisers. With the introduction of the IOR in the early ’70s, their popularity quickly waned, with the exception of a brief burst of interest in lift keels and daggerboards in the late ’70s—a trend quickly stamped out by further rule modifications.

Today, the centerboard in larger production fiberglass sailboats has been mostly replaced by shoal-draft options that incorporate low-aspect-ratio wing or bulb

keels. The rationale is that fixed shoal-draft keels achieve thin-water cruising potential without the complication of a more expensive, movable appendage underwater that is often difficult to repair or access. The wing or the bulb keel also achieves a lower center of gravity that, when married with the wider beams of modern production sailboats, achieves quite acceptable upwind stability, if not good capsize numbers.

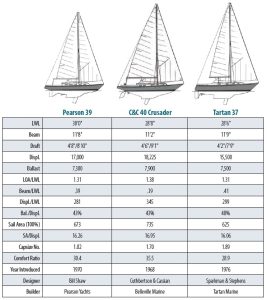

The boats chosen for this comparison span the CCA/IOR transition, with the 1968 Cuthbertson & Cassian-designed 40-foot Crusader firmly planted in the CCA era, the 1970 Bill Shaw-designed Peason 39 right at the transition point, and the 1976 S&S-designed Tartan 37 firmly fixed in IOR. Belleville Marine built the Crusader in 1968 before the official creation of C&C Yachts in 1969, but even then, the decision had already been made that Belleville Marine would build centerboard models designed by Cuthbertson & Cassian, while Hinterhoeller Yachts would build fixed-keel configurations by the same design office.

What makes the Crusader unique in the Belleville offering is that she is the only centerboard configuration that had a separate keel and rudder, not a full-keel centerboarder like my own 31-foot Corvette. Coming out the same year as Red Jacket’s monumental Southern Ocean Racing Conference (SORC) win (“Anatomy of a Legend,” September/October 2021) that firmly established the performance advantage of a separate keel and rudder, this should not be surprising.

Most would say that the Crusader is the largest of the three at almost 40 feet length overall and a respectable 18,225 pounds of displacement. However, her 28-foot 8-inch waterline length is 1 foot 4 inches shorter than the 17,000-pound Pearson’s waterline length of 30 feet, and only 2 inches longer than the 15,500-pound Tartan at 28 feet 6 inches. This shorter waterline on that much displacement is typical of CCA designs and is reflected in the Crusader’s displacement/waterline length ratio of 345, compared to the Pearson at 281 and the Tartan at 299.

This transition from CCA to IOR is also reflected in the maximum beam of each boat, with the “larger” 1968 Crusader being the narrowest at 11 feet 2 inches, the 1970 Pearson the next widest at 11 feet 8 inches, and the “smallest” boat—the 1976 Tartan—having the largest maximum beam of 11 feet 9 inches. This beam difference is reflected in the capsize numbers that follow the same pattern, with the Crusader coming in at a very safe 1.70, the Pearson at 1.82, and the Tartan at 1.89. However, all are well under the capsize threshold of 2, above which boats are considered more vulnerable to capsize.

Sail area/displacement numbers are in the low 16s for the Pearson and the Tartan, and almost 17 for the Crusader, reflective of her larger sail area compensating for her heavier displacement. The CCA-to-IOR transition is also noticeable in the aspect ratio of the mainsails for these boats, as the main becomes chronologically narrower for each, with the Tartan finally sporting something resembling a “ribbon” main.

It is no secret that I am fond of centerboarders and have been involved in the design of a few while I was with C&C and Mark Ellis Design. However, centerboards were never an option offered in the larger boats by Hunter Marine during my tenure, or even before or after, to my knowledge. Most builders now prefer simplicity, and it seems that most buyers of new boats would agree with that philosophy. However, as each of these boats illustrates, there are some very good centerboarders still available on the used boat market that are certainly worth a closer look.

Good Old Boat Technical Editor Rob Mazza is a mechanical engineer and naval architect. He began his career in the 1960s as a yacht designer with C&C Yachts and Mark Ellis Design in Canada and later Hunter Marine in the U.S. He also worked in sales and marketing of structural cores and bonding compounds with ATC Chemicals in Ontario and Baltek in New Jersey.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com