Anybody who lived through, and was part of, the extraordinary growth in offshore racing in the 1970s will be familiar with the name Ron Holland. He and his friend Doug Peterson, and later, German Frers, were the top independent designers of IOR offshore racing yachts in this New Age of Sail ushered by the new IOR rule in 1970. Indeed, Holland points out that these three designers accounted for 49 of the competitors in the 1979 Admirals’ Cup racing — 29 by Holland, 35 by Peterson, and 17 by Frers!

Anybody who lived through, and was part of, the extraordinary growth in offshore racing in the 1970s will be familiar with the name Ron Holland. He and his friend Doug Peterson, and later, German Frers, were the top independent designers of IOR offshore racing yachts in this New Age of Sail ushered by the new IOR rule in 1970. Indeed, Holland points out that these three designers accounted for 49 of the competitors in the 1979 Admirals’ Cup racing — 29 by Holland, 35 by Peterson, and 17 by Frers!

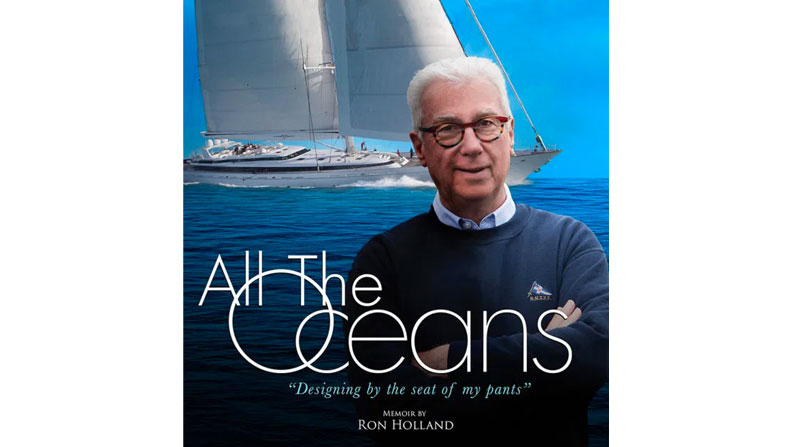

All the Oceans is Holland’s life story eloquently told by the person who lived it. It is an excellent companion piece to Dick Carter’s recent memoir, Dick Carter, Yacht Designer in the Golden Age of Offshore Racing, but while Carter avoids delving into his own personal life, sticking almost exclusively to his design career, Holland reveals to us to all the complications and challenges he faced, starting with his less-than-illustrious school years in New Zealand, where he failed to pass his final high school exams, not once but twice. This led to an abbreviated apprenticeship in boatbuilding, where he designed his first boat before he embarked on his first love — offshore sailing and adventuring, following in the wake of his childhood heroes Captain Cook and the Hiscocks.

One sailing adventure led to another until Holland found himself in California where his design career began. It was here he met Doug Peterson. Well before either established a design reputation, they sailed together on a 33-footer racing from California to Tahiti, a 23-day adventure at sea. Holland would even crew for Peterson on Ganbare when she almost won the One Ton Worlds in Sardinia in 1973, establishing Peterson’s own design career. Prior to that, in collaboration with Warwick Tompkins and designer Gary Mull, for whom Holland was working at the time, the legendary Improbable was designed and built, against all the odds, with the sole goal of winning the Jamaica Race, which she ultimately did.

Holland then established himself in Florida working for Charlie Morgan, where he convinced the St. Petersburg Yacht Club to host the first ever Quarter Ton North American Championships, with first prize including the winning boat being shipped to England to compete in the 1973 Quarter Ton Worlds. With the help of his future brother-in-law, Gary Carlin, Holland built Eygthene, the “shoestring” Quarter Tonner that would win the regatta at SPYC, and then the Quarter Ton Worlds in England, and start Holland on his international design career. Overtures from Ireland led to the design and building of the One Tonner Golden Apple, as well as Holland setting up his rapidly expanding design office in a refurbished stone piggery in Cork. Golden Apple was followed by an increasing number of successful IOR designs, with Imp’s SORC and Admiral’s Cup victories further burnishing his design credentials.

One reference that strikes close to home for me is Holland’s mention of his Canada’s Cup-winning Two Tonner Golden Dazy, which, back in 1974, he considered a “big” boat. I was project manager and crew on the C&C-designed-and-built Two Tonner Marauder, which lost to Dazy in that campaign on Lake St. Clair in 1975, and I agree with Holland that it was John Bertrand’s skippering of Dazy that made the biggest difference in that series. His reference to Dazy being considered a big boat in 1974 illustrates the changes that have taken place in the yachting industry over the years. Holland followed and benefited from those changes, with the definition of “big” rapidly increasing with his Maxis at 80 feet, to his first 100-footer, then 120 feet, 180 feet, and ultimately the 250-foot Mirabella. “Yachting” was moving into the domain of the ultra-rich, and Holland was moving in some exclusive circles. It is no coincidence that the forward to this book is written by Rupert Murdoch, the owner of one of Holland’s 184-footers!

One of the best-written and most memorable chapters in this highly readable autobiography is Holland’s description of his experiences in the disastrous 1979 Fastnet Race aboard the Irish yacht Big Apple. Holland’s descriptions of the wind and sea state during the race are vivid, culminating in the loss of their carbon-fiber rudder and being ordered to evacuate the out-of-control yacht by being lifted out of a partially inflated life raft by a rescue helicopter. This would be Holland’s last ocean race, as the company turned its attention to the design of larger and larger yachts for an ultra-rich clientèle.

The book is illustrated with photos of Holland’s life in sailing and yacht design and with pen-and-ink drawings of incidents described in the book. I found no credits listed for these drawings, so must conclude that Holland drew these himself. If this book has a weakness it would have to do with the complete absence of lines plans of his more successful designs. For instance, Holland explains in some detail his design philosophy in creating Eygthene, so one would think that there would be a lines plan included to better illustrate those concepts. It is not as though anyone would want to steal the lines plan for a boat designed to a rating rule that no longer exists. I would have also liked to see the lines plans of Improbable, Golden Apple, and Imp, not to mention Mirabella, although I could sympathize with not including the latter.

So, this book is not a primer on yacht design, it is the personal story of one of the world’s great yacht designers. I would hazard a guess that no yacht designer, with the exception of GL Watson, has had the scope of work over their careers as has Holland. And he is completely open about his failures as well as his successes, discussing his three marriages, his philosophy of life, his not attending either his father’s or mother’s funerals, the failure of Ron Holland Yacht Design in the early 1990s (just at the time he was having his own cruising yacht built), as well as his recent stroke. The book reveals a lot about the man whose lifelong philosophy was to always say “yes.” I learned that Holland now lives in Vancouver, a move prompted by his third wife and a desire to get back to the Pacific, where it all started.

This is only the third book I have encountered that tells the inside first-person story of yacht design in the modern era, with only Olin Stephens’ 1999 autobiography, All This and Sailing Too, and Dick Carter’s recent book preceding it. Despite its shortcomings in not including as many lines plans as I would have liked, this book is a must-read for anyone who has sailed or raced offshore in an IOR-designed yacht. I thoroughly enjoyed it and now know much more about Ron Holland than I did previously. And, at the end of the book, I very much liked the guy. He sounds like a fascinating person to have a beer with.

All the Oceans: Designing by the seat of my pants, a memoir, by Ron Holland (Ron Holland Design, 2018; 350 pages)