Orkney-born John Rae (1813-1893) acquired many of his survival skills and his toughness from an idyllic childhood. He became a surgeon for the Hudson Bay Company and soon thrived in the challenging environments of the far north. Over his lifelong association with the Company, he became known as a consummate northern traveler and acquired a remarkable knowledge of Inuit culture. It was Rae who first broke the news of the fate of the Franklin expedition and brought back artifacts from the sailors acquired by Inuit informants. This was his main claim to fame, but he has always remained in the historical background.

Orkney-born John Rae (1813-1893) acquired many of his survival skills and his toughness from an idyllic childhood. He became a surgeon for the Hudson Bay Company and soon thrived in the challenging environments of the far north. Over his lifelong association with the Company, he became known as a consummate northern traveler and acquired a remarkable knowledge of Inuit culture. It was Rae who first broke the news of the fate of the Franklin expedition and brought back artifacts from the sailors acquired by Inuit informants. This was his main claim to fame, but he has always remained in the historical background.

Now historian William Barr has edited the explorer’s unfinished autobiography, which reveals the full extent of this seasoned arctic traveler’s achievements. Between 1846 and 1854, he mapped 1,555 miles of new coastline in what is now the Canadian Arctic. He traveled with a small group of men by boat and dogsled, traveled light, relying heavily on hunting and fishing for food. Rae was an amazing walker, especially on snowshoes. In 1851-1852, he snowshoed 1,280 miles on one journey alone. His open-boat journeys involved no less than 6,080 miles along the shores of Hudson Bay and along the Arctic coast. Even after his retirement, he surveyed telephone line routes in the north, as well as across the Faeroes and Iceland. He even guided a few hunting trips, published widely in academic journals, and had places, admittedly mostly remote, named after him. His work was of great importance, yet he has remained in the background until recently.

Barr’s skillful editing of the unfinished autobiography is a meticulous enterprise, based not only on the surviving manuscript but on other primary sources. It’s a book you’ll dip into while anchored somewhere comfortable, evening after evening, entranced by the understated narrative. The boat journeys were undertaken in leaky Company craft built of unseasoned wood, sometimes caulked with a mixture of grease and powdered charcoal. Portages around rapids were routine. Running them was “rough and exciting work”, impossible to avoid when steep cliffs pressed on the water. When conditions were favorable, Rae sailed until stopped by melting ice, which “rubbed the planks.” The passages involved constant searches for open water. When the wind blew hard offshore, the boats scudded along under close reefed sails. Other days, they confronted fog and heavy rain. Rae’s calm account disguises what must have been a very tough journey that examined 831 miles of hitherto unexplored coastline — all without an engine or any of today’s electronics and protective clothing. At the same time, the crews lived off the land.

This monumental volume is a tribute to a truly remarkable arctic traveler and voyager, whose achievements leave one breathless with admiration. In a way, this 648-page book is a true page-turner, largely because Rae writes so humbly about his extraordinary journeys and carries you with him. But I’d recommend taking this unusual, admittedly heavy volume along as an engrossing browse that reminds us how lucky we are to cruise remote waters in comfort. You may stay up all night reading! Barr’s hand guides us skillfully through an Arctic life lived to the full.

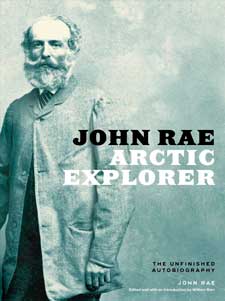

John Rae, Arctic Explorer: The Unfinished Autobiography, by John Rae, edited by William Barr (University of Alberta Press, 2018; 648 pages)